A Market Manifesto For 2015 And Beyond_1

Post on: 21 Май, 2015 No Comment

Summary

- Stock market booms are always associated with the same deviations of basic market relationships in GDP, commodities, earnings, bond yields, inflation, and stocks themselves.

- The current strains on normal relationships suggests commodities and interest rates will bottom in late 2015 while stocks continue to rise.

- This will be followed by an oil shock, a peak in stocks, and a brutal global contraction in 2016-2018.

The earnings yield has always been highly correlated with inflation-adjusted commodity prices. With few exceptions, since the establishment of the Federal Reserve, the earnings yield has been inversely correlated with stock prices rather than being positively correlated with earnings, as was the case under the classical gold standard. And, on the other side of the equation, movements in real commodity prices are almost always caused by movements in nominal commodity prices, not consumer prices. If real commodity prices are rising, it is almost always because nominal commodity prices are rising, not because consumer prices are falling. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that in markets of the last century, stock prices and commodity prices have tended to be inversely correlated with one another.

Interest rates and inflation also have a tendency to correlate with the earnings yield insofar as they have converged with that yield over the last century.

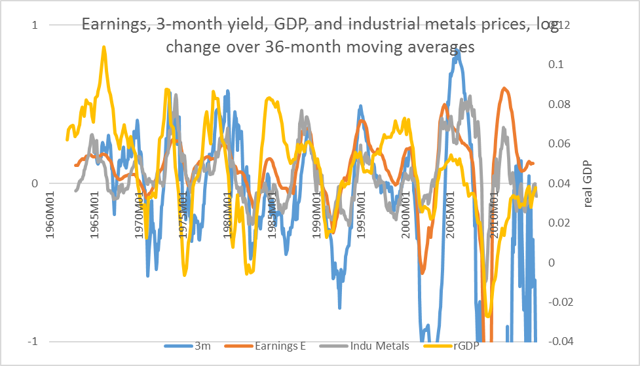

If we change the timescale to look at cyclical fluctuations, however, everything changes. Over the last fifty years, the earnings yield, GDP, interest rates, stock prices, and commodity prices have been positively correlated with fluctuations in earnings. This correlation is strongest in the earnings yield (0.8), industrial metals (0.6), short-term interest rates and certain raw materials (0.5), and stocks, GDP, and commodity prices generally (0.4).

Two things occur, therefore, when we change the timescale: the relationship between the variables and their collective center of gravity. Thus, the earnings yield has moved with stocks over long intervals and with earnings over short. Commodities are inversely correlated with stocks over longer intervals but positively correlated with earnings over shorter durations. And, whereas the earnings yield seems to be the sun around which the market swings from a secular perspective (I prefer to call this supercyclical), at the cyclical level, it is earnings that shine through.

This contrast between relationships at different scales makes it difficult to make predictions, especially about the past. Contrary to country wisdom, the future actually is much easier to describe, because it always appears to us as an empty canvas upon which certain logical lines will inevitably unfold. The actual future is going to be, like the past, a mangled mess of contradictions, of course, and that’s the future I am going to try to describe here.

But, there is a simple principle organizing it all, which is that at both the cyclical and supercyclical levels, deviations from normal market processes have a single, important variable in common, which is that they all occur during stock market booms. To put it somewhat more rhetorically, it does not matter a wit whether interest rates or commodities or inflation go up or down; in a sense, it does not even matter if stocks go up or down. The only thing that matters is what every other factor is doing at the same time. I have written about a few weird and otherwise inexplicable intermarket relationships over the last three years, and most of them are either expressions of regular intermarket relationships or deviations from them, all of which occur during booms.

For example, my first two articles for Seeking Alpha, back in 2012, pondered the possibility of an oil shock occurring over the following year. Two fairly reliable predictors, the yield curve and the gold/oil ratio appeared to be saying different things, and I could only recommend that investors hedge against the possibility of an oil shock when oil retouched its previous low. Fortunately, oil rose from those lows but did not spike. I now have a clearer understanding of why it is that the yield curve and the gold/oil ratio should happen to predict oil prices and why it is that one works better than the other depending on market conditions. In short, gold, oil, and short-term yields each have their own ways of relating to the cycle and their own ways of responding to cyclical distortions under boom conditions. It is now apparent that the gold/oil ratio is signaling an oil shock, probably in early 2016, although we have to wait for the ratio to peak to be sure.

These distortions explains a lot of strange things about the market. In 1987, stocks crashed for no other apparent reason than that the price of oil jumped. The reason oil jumped was because the cycle was turning up again, and oil had fallen unusually low in the previous cyclical downturn (1985-86) after having failed to peak with the cycle in 1984-85. While oil was collapsing, gold was rising, thus lifting the gold/oil ratio.

In 1986, the yield curve was the flattest it had been for five years, even though, as we just said, the cycle was troughing. Because short-term interest rates are more volatile than long-term interest rates, the yield curve spread should always be high when the cycle is troughing, but under boom conditions, short-term rates are unusually stable relative to long-term rates. So, while short-term yields were falling with the rest of the cycle, as one would expect, long-term yields were falling faster, thus flattening the yield curve spread. In that way, the flattened curve predicted the oil spike of the following year.

The yield curve spread really works best under normal market conditions, though. During booms, it can produce too many false positives, as it did in the late 1990s. I suspect, however, that as Treasury yields continue to fall over the next nine months, and the yield curve steepens, it will confirm the gold/oil spike’s signal. For a fuller description of what to look out for with respect to bond yields and the gold/oil ratio, I would not change much of what I wrote in those two older articles. The present spike in the gold/oil ratio is a near-textbook example of what happens before an oil shock.

Interestingly, the yield curve and the gold/oil ratio are both relatively new-fangled things. What I mean is, there was really no such thing as a steep yield curve under the gold standard, because short-term yields were always higher than long-term yields, and the gold/oil ratio would simply have been an odd way of describing the inverse of the price of oil. Also, although short-term yields have been dependably correlated with the earnings cycle over the last fifty years, such does not appear to have been the case before the 1960s.

So, how many of these variables were positively correlated with earnings before the 1960s?

Real GDP appears to have been, but the Fed only provides quarterly data back to 1947. Monthly data for short-term yields only goes back to the 1930s, and the World Bank provides monthly data for commodities only back to 1960. For commodities, though, we have some alternatives. The Bureau of Labor Services (BLS) has a nonferrous metals index that goes back to 1947 and an industrial commodities index (PPIIDC) that goes back to 1913. Both of those indexes have been positively correlated with the earnings cycle.

But, what about before 1913? I think that in this instance we can use consumer prices as a proxy. Because that index was composed entirely of goods before the service economy began to displace the manufacturing economy, and because many of those goods were commodity-like (e.g. foodstuffs), they give us an imperfect but plausible picture as to the status of the cyclical relationship between commodities and earnings at that time. As it happens, the correlation between the two was remarkably high. It is all the more remarkable because of how weakly correlated CPI is with earnings today.

Strictly speaking, that really only tells us about the change in the relationship between CPI and earnings, but I think that is a pretty strong hint that not only were commodities and earnings highly correlated with one another but that correlation was even stronger than it is today.

Let’s suppose that is the case. If CPI was so highly correlated with earnings before 1913, and only industrial metals have a comparable degree of correlation today, then we have to assume that a breakdown in that relationship has occurred in agriculture prices, and that the cyclical relationship appears to be strongest between industrial metals and earnings. The fact is, though, that we are reduced to making educated guesses about the historical relationship between metals and earnings cycles.

We do have long-term annual prices for commodities and producer price indexes, however. Lots of them. If we take the seven-year rates of change of commodity prices and earnings since 1871, we find that they are positively correlated, even agriculture prices. The strongest correlations with earnings are metals (0.6) and the weakest, fuel (0.4).

There have been a handful of points at which the growth rates in commodities and earnings have deviated from one another, sometimes quite radically, even metals prices. Most of these deviations have involved a spike in earnings growth that was not registered in commodity prices. The points of maximum deviation, according to the rolling correlations, were the late 1920s, late 1960s, late 1990s, and the 2010s. These all happen to have been major peaks in the stock market. In terms of differences in the rates of growth, the highest spread between earnings growth and producer prices were in the early 1900s, late 1920s, and late 1990s. Again, these deviations coincide with peaks in the stock market. As I pointed out in a slightly different context earlier last year, any earnings growth rate whose base begins in late 2008/early 2009 will almost certainly be astronomically high unless earnings collapse 90% again. Such a collapse is not likely until after commodity prices (including crude oil price) and interest rates recover considerably and then nosedive with the rest of the market and the economy (much as to in 1998-2001).

Again, the larger point here is that booms coincide with deviations in the fundamental relationships. The sorts of deviations we are talking about run eight years at most. It would be unprecedented if the current stock market boom lasted much beyond the spring of 2017.

I have not used the word bubble to describe these deviations, because that word carries too much ideological baggage, suggesting that somebody somewhere is being reckless, the market collectively or the Fed or whomever. Just because short-term rates behave differently during booms does not mean that Fed policy caused the boom, and just because a boom coincides with temporary deviations in market relationships does not mean that the boom is due to unrealistic expectations about the future.

Viewed from a neutral perspective, the market simply experiences breakdowns in normal relationships from time to time. Some of these are so small that they can only be seen when compared to similar variables (as when we compare yields through the yield curve or two commodities through commodity ratios). Some are larger, such as the breakdown in the cyclical relationship between GDP and earnings.

Recessions coincide with cyclical troughs in earnings, but not every trough has seen a recession. Not only does GDP growth remain positive during those deviant troughs, but the economy tends to accelerate as the rest of the cycle weakens and continues to accelerate as the cycle picks up again, until it slams right into a recession. Such was the case in the late 1980s and late 1990s, and it will likely be the case in a couple years. The late burst in GDP growth and the collapse in oil prices we are witnessing now are characteristic of this kind of boom.

To be clear, the conditions that signal recessions are not the same as those that signal stock market crashes, but they are similar. Recessions only occur during cyclical troughs. If a recession is missed, it will not occur until the next trough. Recession was avoided in 1986; the next one did not hit until 1990. Recession did not hit in 1998; the next one came in 2001. No recession occurred in 2013; we will have to wait until well after the current rout in commodities reverses for the next one.

Much the same is true for stocks, except that the deviation in stock market behavior is far more radical, inasmuch as stocks become inversely correlated with the earnings cycle when they boom. This has been true for the last 140 years, although the extent of this deviation has become increasingly persistent and radical over the last century. The severity and duration of these deviations coincides, as it happens, with both the long-term breakdown in the relationship between cyclical fluctuations in CPI, agricultural commodities, and earnings and the rise of the correlation between short-term rates and earnings that we talked about above. It is difficult not to link this longer-term, underlying shift in relationships to changes in the monetary order, but that is a different argument.

One final question worth considering is whether or not even the word deviation is appropriate. Booms are experienced as a series of deviations from identifiable market relationships, but is a boom a deviation from what should have otherwise occurred? Is there something unnatural about a boom, or is it a normal function of markets? In other words, the regularity of these deviations makes one wonder if they really are deviations. It is possible, I think, to hold that deviations are not unnatural but that their increased frequency may be.

To conclude this article, I am going to try to make a case for viewing deviations as a normal stage in the progression of the supercycle. That brings us back to the relationship mentioned at the beginning of the article, the strong correlation between real commodity prices and the earnings yield.

As it happens, not only are real commodity prices correlated with the earnings yield, but the long-term rates of growth in nominal commodity prices are also correlated with the earnings yield. In fact, if we look at the chart of the two, it almost appears as if the earnings yield forms an upper bound to commodity price growth rates. In any case, the two have been converging in much the same way that bond yields and inflation have converged with the earnings yield.

That also raises the question of the relationship between earnings growth and the earnings yield. We have already mentioned that earnings growth and commodity prices are positively correlated except when earnings growth jumps abnormally high. We also know from Shiller that the stock market cannot long endure the rate of earnings growth rising above the earnings yield. (Insofar as the P/E10 ratio equals the rate of earnings growth divided by the earnings yield).

In effect, we have a cluster of relationships between the earnings yield, earnings growth, and commodity prices, with commodity prices at the center. The earnings yield and commodity prices (either absolute prices or their long-term rates of change) have peaked on average every thirty years since World War I. So, peak to peak, we can posit three completed cycles since then (roughly, 1920-1950, 1950-1980, 1980-2010). Now, if I am right that the earnings yield and commodity prices formed the basis for Keynes’s so-called Gibson’s Paradox and the Kondratieff Cycle, both of which faded around the same time, that would suggest that the duration of supercycles has been cut in half for some reason over the last century.

New supercycles always begin as a sudden bout of disinflation. This was true for the beginning of all four supercycles, although to differing degrees, and was evident in commodity prices, inflation, earnings growth, and the earnings yield, and (except for the beginning of the 1950-1980 supercycle) bond yields, too. This also appears have been true for the conclusion of the previous cycle in the 1860s and before that, in the early 1800s, although the peak in commodity growth rates (using UK data) was a good decade before absolute prices peaked.

Once that shock stabilizes, stocks then take over. The earnings yield declines primarily under the impetus of stock market growth.

Once the earnings yield has hit a sufficiently low level (it appears to be around 5%), earnings growth surges, stocks boom, and commodities collapse. These are typically the periods of highest growth, and they are also the conclusion of the boom portion of the supercycle. This concluding period never lasts more than six to eight years.

At the very end of that boom, inflation and commodities turn up ever so gently, and then everything crashes: stocks, earnings, commodities, yields. Commodities and yields are already at very low levels, but they manage to squeeze even lower.

The severity of the post-boom crash varies. It can be merely as unpleasant as the recession of 2001 or as earth-shattering as the Great Depression. Once that crash has stabilized, the final portion of the supercycle begins: a rise in commodities, inflation, yields, and earnings growth. Normally, stocks do not respond especially well to this phase. This phase tends to last less than a decade and is marked by very normal market relationships where everything (stocks, GDP, inflation, interest rates, earnings, and commodities) march together in cyclical unison (as was the case in the 2000s).

If modern supercycles have typically lasted thirty years, the period from the initial peak to the base of the next upswing has typically taken about twenty years, irrespective of when the boom occurs during that supercycle. What that has meant is that, if stocks are not prepared to carry the earnings yield down to the end of that portion of the supercycle, a collapse in earnings and commodity prices will. That is what happened in the Great Depression. The surge in earnings and stocks came in the first decade of the supercycle, leaving the 1930s to pick up the pieces.

In other words, it appears that the size of the collapse that follows the boom appears to be inversely proportional to the speed with which the boom appeared, and the earliness of the boom seems to be a function of the sharpness of the initial, disinflationary shock. That is a confusing way to put it, perhaps. If the disinflationary shock is sudden and severe (as in the early 1920s), the earlier the concluding boom will come; and the earlier that boom, the longer the post-boom crash will last. In the 1950s and 1980s, the disinflationary pressure was far gentler than it had been in the 1920s; the subsequent booms were longer, and the post-boom crashes relatively mild.

At the beginning of the present supercycle, the disinflationary pressures have been comparable to those in the aftermath of World War I. Even if earnings fall by 50% over the next two years, the long-term growth rate in earnings since 2009 will still have been the single greatest episode of earnings growth ever by far, and such periods are always episodes of strong stock markets, almost inexplicably weak inflation, followed by crashes and low rates of return. The big question is not so much if or even when but how bad the bust will be.

Unless the present supercycle is going to be far more truncated than it has been over the last century, or unless the nature of the supercycle is going to change altogether, it seems likely that the present boom will be followed by a Depression-style crisis around the end of the decade. At the moment, it looks as if the cycle (earnings, commodities, inflation, and interest rates) will bottom over the course of 2015 (while stocks (SPY. DIA ) and the general economy continue to rise), oil will spike in 2016, stocks will peak in 2017, and a severe economic collapse will be in place by 2018. I would not expect these targets to be off by more than six months.

So, this year, I will be keeping an especially close eye on when and where the gold/oil ratio tops out, how low long-term interest rates will fall, and for a cyclical trough in industrial commodities (not just the metals but raw materials and energy). Sometime near the end of the year, I suspect we will start to hear less about supply gluts and more about overheating and the dangers of inflation returning. If not then, then early next year, the Fed will probably all of a sudden find itself raising rates faster than it had anticipated. When short-term rates rise significantly faster than earnings, recessions have always followed. With rates at zero-point-zero-eight, or wherever they are at the moment, even raising rates to 0.25% would be, assuming that relationship holds, catastrophic.

Disclosure: The author has no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More. ) The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it. The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.