Want to buy shares this week in the Alibaba IPO Hand over your money and keep your mouth shut

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

The IPO of Alibaba is shaping up to be the largest that the world has ever seen, on track to raise as much as $25bn for the web portal that is China’s version of Amazon.com and eBay combined.

But in spite of all the buzz, it may not come close to generating the kind of frenzy among investors that its size or significance might suggest. The reason? The company’s ownership structure.

It can be summed up this way: we will take your money, but we’re not interested in your ideas.

Alibaba’s controlling group of shareholders are quite happy to raise capital from new investors and give them an economic interest in the business.

But when it comes to giving them a say in how that business is run, it’s quite another matter.

At the Chinese company, power will be concentrated in the hands of a 28-person partnership. That group will have the right to name a majority of the company’s directors, thus giving them effective control of the business.

True, Alibaba’s new shareholders will still be able to vote against any of those nominees. But all that would happen is that the partnership would go back to the drawing board and come up with replacements it prefers.

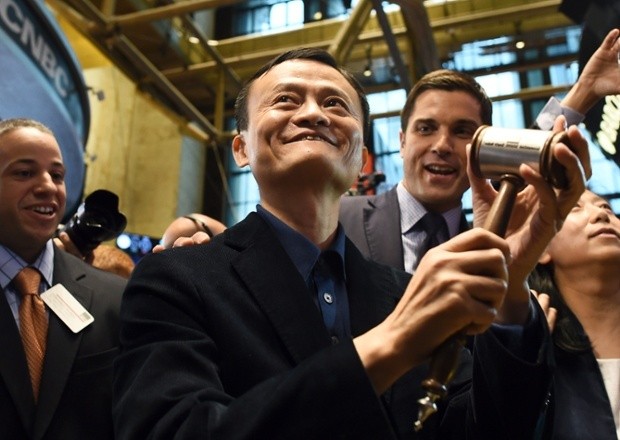

A small group of insiders will control the company’s strategic direction. If they’re unhappy with the way Alibaba’s management team, lead by founder Jack Ma, is handling the business, or if they want to insist that the company consider an unsolicited acquisition offer, there is literally nothing that an unhappy outside investor can do other than to sell his shares.

Company insiders, on the other hand, are living easy; outsiders are left gazing hungrily on as these privileged folk consume the feast paid for by their investing dollars.

Investors who think a share of stock buys any power at tech companies are reduced to this position. Photograph: Getty

The problem isn’t just about Alibaba. In fact, Alibaba’s massive transaction simply serves to remind us all that it could have been still worse had the company opted for an even more blatant form of shutting out investors: adopting a dual or multi-share class structure.

It is something that plenty of other companies – like Google and Facebook – are doing. It works like this: a Class A share – the kind sold to the public – might give you a vote. A Class B share – the kind that the insiders have – entitles its owner to 10 votes per share.

That’s the kind of structure that gives Rupert Murdoch and his family control of 40% of News Corp, even though they own only 12% of the company’s outstanding stock. It ensures the Murdochs have an outsize influence in how the media empire is run, even as they have whittled down their economic interest – and it also has helped them win a vote on whether that dual share class structure should stick around.

Any company that adopts a dual- or multi-share class structure is doing so to give one group of shareholders a different set of rights than another. Let’s be blunt: they’re giving one set of shareholders, usually insiders, greater rights, and locking them into place in perpetuity. Outsiders can own only powerless stock.

We became wise to this trick – once. Now it’s forgotten. Back in the 1990s, this was all starting to look like a legacy of the bad old days of crony capitalism. Only media companies – often family-owned – managed to defend dual share structures with a straight face by pointing to their public interest mission and the risks of exposing it too much to commercial pressures.

The philosopher-king CEO class may be oft-hailed leaders now, but what happens when they pass their companies on to someone else? Here, Google’s Sergey Brin. Photograph: Eric Risberg/AP

Then the Google guys – founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin – changed the way the game was played by deciding that their much-anticipated 2004 IPO would feature a dual-class share structure. Now, a dual share structure is an almost-routine feature of a technology stock IPO, to the point that when Twitter went public without it, the fact was worthy of comment.

Defenders of the dual-class share system argue that founder-led companies are far, far more likely to thrive and be innovative on their own. They argue that when investors like pension funds and other big institutional investors pick management teams or suggest new directions for companies, the companies won’t deliver outsize returns and growth to their shareholders.

Would you want anyone but Warren Buffett in control of Berkshire Hathaway, they argue, or “the Google guys” – Sergey Brin and Larry Page – at the helm of Google?

Well, probably not, is the honest answer.

But here’s the rub. Sure, it’s true that a dual-class structure shelters a visionary founder from the pressure to meet quarterly earnings goals or else risk being driven from the firm by short-term minded investors brandishing pitchforks.

But there’s another way to do it, one that doesn’t require disenfranchising those investors and assuming that they are dolts with their minds fixated on the next three months.

Jeff Bezos, for instance, has consistently managed Amazon.com with an eye on the long term – sometimes, the very long term. While investors haven’t always shared that long-distance vision fully, for the last several years they have been remarkably patient, rewarding the company with sky-high valuations in spite of its anemic profit margins.

And Bezos accomplished it without the benefit of two tiers of stock.

What can other tech CEOs learn from Jeff Bezos? For one thing, accountability to investors. Photograph: JOE KLAMAR/AFP/Getty Images

Moreover, for every Google or Berkshire Hathaway, there is at least one company where the jury is still out on its performance. Many others are cautionary tales of what happens when you entrench management and eliminate accountability to outside pressures. Worldcom had a dual share class structure; so did Enron.

And this year, Google – which got the ball rolling in 2004 – went a step further still. It created a share class that has no voting rights whatsoever . This is a vast departure from the common practice in the stock market, which is: one share, one vote.

Not at Google. Brin and Page will happily accept your money in exchange for some Class C shares. They just don’t want you to say anything at all about how they run the business. The company’s Class A shares give one vote apiece. Its Class B shares – owned mostly by Brin and Page, giving them 55.7% voting control of Google – provide 10 votes for each share.

You may not be worried, because you think that folks like Brin, Page, Buffett, Zuckerberg, etc, will act in your best interests as a shareholder. That’s super. But this is the kind of problem that defenders of absolute monarchies encounter. Monarchs and CEOs are mortal; the systems they put in place can live on after them.

Will Mr Buffett’s heirs be as sage as he has been? Should someone buying Google’s Class C shares be forced to rely on the ability of Brin and Page to magically convey their talents to the next generation?

I don’t think so. Nor do a growing number of institutional investors. And it’s time for individuals to stand up and be counted.