Trading the carbon market

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

London (CNN) — Debate is rife in Australian political circles about whether carbon trading is the way forward for climate change abatement.

Carbon trading is said to be one way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

There, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is looking to introduce a mandatory carbon trading system by 2010 which will cap the amount of pollution industry can release. The proposed Australian system will be similar to the European Union emission trading system which was established in 2005.

With Phase 1 of the European system complete, there are a few lessons about carbon trading that Australia — and other countries looking to go down this path — could benefit from.

So what is carbon trading?

Carbon trading — also known as cap and trade — is a system designed to cut the carbon emissions which contribute to global warming. Generally in a market-based cap and trade system, a central authority — such as a government or international body — sets a limit on the amount of carbon which can be emitted and then divides this amount into units which are allocated to different groups. These units can then be traded as any commodity would.

Carbon trading can occur both between countries and amongst industries within countries.

A second approach to carbon trading involves a country or business generating carbon credits by investing in green projects — usually in developing countries — that are said to reduce emissions.

Why is it necessary?

According to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) there is unequivocal evidence that human activities have contributed to a gradual warming of the planet which has resulted in a change in climate. The IPCC report provides scientific evidence of change including to the duration of seasons, rainfall patterns and an increased frequency of extreme weather events.

Industrialization is recognized as a key factor in the increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphere and according to the IPCC the world has warmed by an average of 0.74C in the past 100 years. The IPCC predicts that if GHG emissions continue to rise at their current rate, this century will see a further 3C rise in the average world temperature.

While the consensus of the scientific community (via the IPCC) is that action must be taken to avert the worst impacts of climate change. economic arguments about the cost of climate change abatement — advanced by countries like the U.S. and at one time Australia — have in the past proved an impediment to action. A carbon trading system is said to be one way that countries can look to make greenhouse gas emissions cuts with minimal economic impact. Do you think carbon trading is the way to reduce greenhouse emissions?

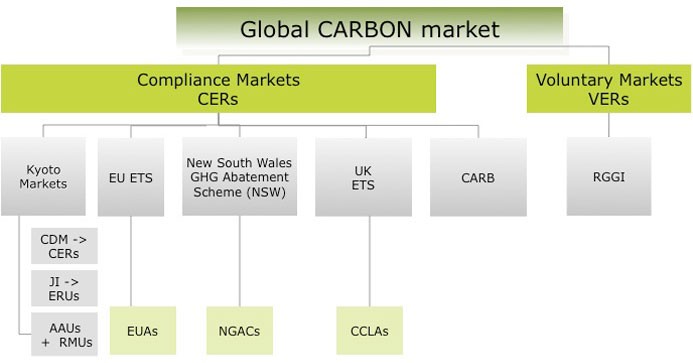

What trading systems exist?

Established in 2005, the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is the largest multi-national, multi-sector CO2 trading system in the world. The ultimate aim of the system is to ensure that EU Member States are compliant with their Kyoto Protocol commitments and to do this the most energy-intensive industries are allocated carbon permits by Member States which allow them to emit a certain amount of CO2. If these companies want to emit more CO2 than their permits allow for, they are able to buy them from more efficient companies with spare permits.

The EU ETS takes in around 12,000 installations which account for around 50 percent of EU greenhouse gas emissions from industries such as power, steel and cement manufacture. According the World Bank. the EU ETS contributed $50 billion of the $64 billion traded in the carbon market in 2007.

Don’t Miss

The second largest carbon trading system exists under the United Nations Kyoto Protocol. The Protocol — which sets binding emission targets for 37 industrialized countries — permits emissions trading in order to help countries meet their agreed upon targets. Countries have agreed to an average 5 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions, compared to 1990 levels, by 2012 and carbon trading is one way to meet this quota. By December 2008, the EU ETS will link up with the UN trading system to create a more global scheme.

The Clean Development Mechanism is a further carbon trading mechanism of the Protocol which allows industrialized nations to claim emission credits from investment in clean technologies which will offset carbon in developing countries. Developed nations can also finance emission reduction projects in developing countries through Joint Implementation in exchange for emission credits.

New Zealand has established a mandatory carbon trading system this year and Australia has also committed to expanding the pioneering New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme to a national market by 2010. New mandatory systems are being considered for Japan and Canada.

Voluntary carbon markets also exist, with the Chicago Climate Exchange one of the more established ones.

What do permits cost?

The cost of a carbon permit is dictated by the market forces of supply and demand. In 2007, one European Union Allocation (for one ton of carbon) was trading at $30 to $35.

What industries are subject to trading?

Under mandatory schemes like the EU ETS, it’s the most energy-intensive industries within Member States which are subject to carbon trading. This includes industries like power installations, steel and cement manufacture and the construction industry. The commercial aviation industry — which accounts for 3 percent of EU emissions — could be brought into the EU ETS by 2011.

Currently personal or household emissions and the public sector and transport industry emissions are not included in any carbon trading system.

Has emissions trading been successful?

Yes and no. The introduction of mandatory systems which cap emissions like the EU ETS is a step in the right direction for trying to cut emissions without a major cost to business. However, critics such as Carbon Trade Watch argue that the current carbon trade systems are flawed because there is a tendency for the biggest polluters to be over-allocated permits.

This was clearly evident with Phase 1 of the EU ETS when the market virtually collapsed in 2006 because too many allowances were allocated. Market analyst Franck Schuttellaar estimated that the United Kingdom’s most polluting companies made windfall profits of around $1.7 billion as a direct result of generous carbon credit allocation under the EU ETS.

Questions have also been raised about whether carbon trading systems actually reduce GHG emissions. Independent UK think-tank Open Europe reported that between 2005 and 2006 emissions from industries covered by the ETS actually rose in UK by 3.6 percent and by 0.8 percent across the whole of Europe.

Auctioning off carbon credits at the outset — rather that simply allocating credits to business for free — is one way that has been proposed to help the system make a real impact on emissions. Certainly, increasing the scarcity of carbon credits would help ensure that businesses commit to genuine low-carbon alternatives.

While carbon emissions account for around 70 percent of greenhouse gases, they are not the sole cause of climate change and it would seem a safer bet to reinforce a carbon trading system with other legislative measures aimed at reducing emissions.

E-mail to a friend