The fallout from Enron

Post on: 26 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

THE bankruptcy of Enron—the worlds biggest-ever corporate failure—has left no one looking good. Auditors, who successfully fought off tougher regulation last year, will find it harder to do the same now. Rating agencies were left behind by unfolding events. Enrons long-term bankers are nursing hundreds of millions of dollars of losses after failing to see the gathering storm. And everyone is asking whether politicians and Texan judges were swayed by Enrons contributions to their election expenses.

As every day passes yet more astonishing news trickles out about the firm. First, it emerged that Enrons auditors, Andersen, whose employees regard themselves as a cut above other auditors, had destroyed documents. Then it was revealed that the document-shredding had continued after the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) had launched an investigation. Then it was revealed that Sherron Watkins, a former Andersen employee who went on to work for Enron, had been so troubled by the Enrons accounting policies that she discussed them with her former colleagues at Andersen and sent a detailed memo to Enron’s chief executive Kenneth Lay.

Mr Lay resigned as chairman and chief executive this week, although he remains on the board. Also this week, yet another Enron employee claimed that her own colleagues had been shredding documents as late as last week. But it is not just Enron itself, and its greedy senior management, or Andersen, who are tarnished by the affair. The failure of Enron raises questions about a host of other outsiders—rating agencies, regulators, politicians, judges, bankers and even the media—who should have spotted that something was amiss a lot earlier.

Lay repays a loan

Related items

Nevertheless, the biggest failure seems to have been within the company itself. Enron established special-vehicle partnerships whose main purpose seems to have been to keep debts and losses out of its own accounts. Enrons chief financial officer, Andrew Fastow, had an interest in some of these partnerships, a relationship that caused the auditors at Andersen to fret—but do nothing—about a potential conflict of interest.

Mr Lay himself has also come under scrutiny. Over three years he received more than $200m from Enron. That did not stop him needing personal loans from the company, which he repaid by selling Enron shares before it collapsed. Normally such share-dealings are subject to rigid restrictions—senior employees are generally banned from buying or selling stock if they have material, private information. When they are allowed to sell, they have to disclose that fact within ten days. These rules are designed to prevent insider dealing and the creation of false markets. However, remarkably these restrictions do not apply if the share sale is to repayments of employer loans.

Andersen’s behaviour is also coming under intense scrutiny. The auditor approved Enron’s accounts despite having significant concerns about the partnerships, Mr Fastow and the financial controls at Enrons new broadband-trading division, and noting that the company was “aggressive in its transaction structuring”. The accountants endorsement meant that investors—bondholders as well as shareholders—were basing their decisions on potentially misleading information.

Andersen is now fighting for its life. Its Chicago head office is trying to pin the blame on the Houston office, where it has disciplined eight auditors. This strategy will be somewhat difficult to sustain given that Andersen used to take pride in the degree of integration across the firm. David Duncan, the sacked lead auditor on Enron, has said that he discussed his actions in detail with Chicago colleagues and that the document shredding only took place after an e-mail from Andersens Chicago-based in-house lawyer, Nancy Temple.

Mr Duncan, Michael Odom, a Houston colleague who has also been disciplined, Ms Temple and Dorsey Baskin, a Chicago-based accounting principles expert, are scheduled to appear in front of a congressional hearing on January 24th. Mr Baskin is a last-minute substitute for Joseph Berardino, Andersen’s chief executive, who says he is willing to appear, but not for a few weeks. Mr Duncan has indicated that he will plead the fifth amendment, refusing to answer questions for fear of incriminating himself.

Berardino tries to explain Reuters

Despite the rivalry between the big five accounting firms, Andersens woes have been viewed with dismay by the rest of the profession. After the Enron scandal initially broke, the five closed ranks to back a statement by Mr Berardino implying that the problem was in overly legalistic accounting rules rather than in the professions ethics.

Like Andersen, other big-five firms have had run-ins with the SEC before. KPMG has just been rebuked by the SEC for investing in a fund that it audits. Two years ago PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) was found guilty of thousands of infractions of the SECs conflict-of-interest rules. In 2000, the big five fought a concerted and successful effort against a ban on auditors performing other work for their audit clients. The accountants put forward the rather implausible argument that, far from this practice allowing conflicts of interest, it enhanced the quality of the audit.

The experience at Enron, which last year paid Andersen $25m for its audit, and $27m for non-audit services, would seem to refute this claim. Already, Harvey Pitt, the SECs new chairman, has outlined stricter regulation. Mr Pitt, who had been conciliatory towards the profession, is now set against self-regulation. Unfortunately, Mr Pitt did not consult the Public Oversight Board, the professions current regulator, before outlining his plans. They were so irritated by this that they disbanded themselves, leaving a vacuum in accounting regulation.

Many investors have questioned whether regulators ought to do more. Mr Pitt has pointed out that the SEC has limited resources. However, it is interesting that Enron was as much of a trading company as are the giant Wall Street investment banks, but avoided any regulatory oversight of that sort at all. During the early 1990s, it had lobbied successfully to ensure that energy trading was exempted from regulation by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The CFTC was chaired at the time by Wendy Gramm, the wife of Senator Phil Gramm, the chairman of the powerful banking committee. Mrs Gramm later joined Enrons board. The Gramms’ Enron investment has declined $600,000 in value because of the company’s troubles.

Given the length and breadth of the relationship, the banks should have had some inkling about what was going on. Did greed got the better of their risk-management models?

Enron was a generous political contributor, to Democrats and Republicans alike, though it gave more to Republicans, including President George Bush. So far, there has been no evidence of any wrongdoing. However, the debacle—and Mr Lays attempts to wield influence at the White House—have raised the issue of campaign-finance reform again. It has also shone a light on the system of judicial elections in Texas. It is one of a handful of states that elects justices to the states highest court, and Enron made contributions to Texan justices, even though it was often engaged in legal cases in the state.

Mr Bush expressed “outrage” this week at the fate of Enron employees. Many of them had invested pension savings in their employer—savings that are now worthless. Many congressional committees are now looking at whether pension funds should be restricted from making such investments, as they are in other countries, such as Britain.

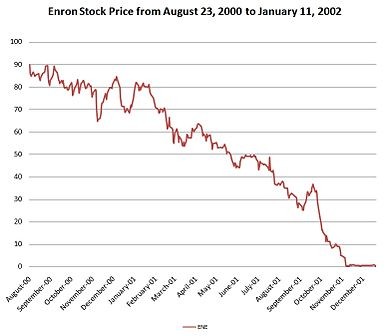

The financial industry has been made to look at best incompetent and at worst corrupt over Enron. Share analysts continued to tout the stock even as the accounting problems unfolded. Analysts are often under pressure to puff stocks to benefit either their trading or investment-banking colleagues. Rating agencies also dragged their heels over downgrading Enrons debt. The market had begun to trade Enrons debt at “junk” levels even while the agencies continued to rate it as investment grade. Now both Moodys and Standard & Poors, the two biggest agencies, have announced internal reviews to see if they can make ratings more responsive to changes in companies underlying performance.

Enrons two long-standing lead bankers have been left with big holes in their accounts after writing down their Enron exposure. Citigroup and J.P. Morgan Chase have been Enrons bankers for years. Both had extensive relationships with the oil trader, advising on deals and underwriting capital raising as well as lending money. The new breadth of the relationship has only been possible in recent years due to the reform of Depression-era laws which had separated lending from capital-market activities such as investment banking. Given the length and breadth of the relationship, the banks should have had some inkling about what was going on. Did greed got the better of their risk-management models?

As the congressional testimony unfolds over the coming weeks, there may be more shocking facts that emerge about Enron. But even what is known already will provide accountants and legislators with more than enough to do in the next few years cleaning up the mess left by Enron’s collapse.