The Case Against Carbon Trading

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

The Case Against Carbon Trading

Kevin Smith

Editor’s Note: The Bali summit has, yet again, put the world into somewhat of a ‘but wait’ mode. Life continues for most, with many hoping/trusting that politicians will ‘work it out’ and bring solutions to the table in, say, two years or so. But, while we wait, I think it’s not a bad idea to really examine what exactly we’re waiting for. While politicians seek to find some agreement on carbon trading, here on Celsias we’re having an interesting discussion on the potential merits of such a scheme. Below is the latest in this discussion (see here and here for previous posts in this discourse). Input from our readers is welcomed.

One constantly hears the refrain that we’ve learned our lessons and that ‘the kinks have been ironed out’ with each successive experiment or round of emissions trading, and it just never seems to actually happen. How much longer can we give this untested and ineffectual experiment time to start working with such a small window of opportunity to mitigate the worst impacts of the threat of climate change?

The precursor to Phase 1 of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) was the UK-Emissions Trading Scheme, a pioneering trial phase of nation-wide emissions trading that would give the companies an idea of how it would work in the larger EU-wide scheme. Here we see some of the obvious lessons learnt that could have been applied to the EU-ETS, but weren’t. An investigation of the scheme from the parliamentary National Audit Office reported that some companies’ targets may be undemanding, and that in some key cases emissions baselines were well above direct participants’ emissions at the start of the scheme.

Labour MP Gerry Steinberg described the scheme as a ‘mockery’ and an ‘outrageous waste of public money’. Over-generous baselines meant that four companies, Ineos Fluor, Invista, BP and Rhodia, massively over-complied in the first year.

The fact that their emissions were already controlled under other environmental regulations led Edward Leigh, the Conservative chair of the Public Accounts Committee, to observe that the scheme seems to be paying [the four companies] £11 million for keeping emissions down to levels they had already achieved before they joined.

Then there’s already been some mention of the disaster of Phase 1 of the scheme. Under sustained corporate lobbying, almost all EU governments made huge over-allocations of permits to industry in the first phase. In 2005, the first year of trading, the relevant industries across Europe emitted 66 million tonnes less than the cap that had been allocated. This meant that the cap was effectively meaningless as it had not forced any net reductions. A preliminary analysis of the 2006 data shows that 93 per cent of the 10,000 installations covered by the ETS emitted less than their allotted quota, in all 30 million tones less than the total EU-wide allocation.

Successful corporate lobbying also meant that permits were allocated free of charge to industry in the first phase. But companies have been passing on the ‘cost’ to consumers anyway. A study by UBS Investment Bank showed that the first round of the ETS has added 1.3 euro cents to each kilowatt hour of electricity sold. This sounds negligible, until you consider that the German minister for the environment estimated that the four biggest power providers — Eon, RWE, Vattenfall and EnBW – had profited by between €6 billion and €8 billion from passing on the imaginary cost of the first phase of the ETS onto consumers.

A year ago, Citigroup’s Peter Atherton confessed in a PowerPoint that the EU-ETS had done nothing to curb emissions and acted as a highly regressive tax falling mostly on poor people. On whether policy goals were achieved, he admitted: Prices up, emissions up, profits up. so, not really. Who wins and loses? All generation-based utilities — winners. Coal and nuclear-based generators — biggest winners. Hedge funds and energy traders — even bigger winners. Losers. ahem. Consumers!

So how are things supposed to have improved in the second round of the scheme?

For starters, governments are allowed to auction off a percentage of permits to industry rather than simply handing them out for free. Yet in practice, only 10 EU members have chosen to go down this route and, of these, four are auctioning fewer than one per cent of their total allocations. Yet free-allocations to fossil fuel intensive industries continue – in effect, providing a huge subsidy to the heaviest polluters. In the article “Implications of announced Phase 2 National Allocation Plans” (NAP) from the journal Climate Policy, Dr. Karsten Neuhoff (from the Cambridge University faculty of economics) and his co-authors conclude that “the level of such subsidies under proposed second phase NAP is so high that the construction of coal power stations is more profitable under the ETS with such distorted allocation decisions than in the absence of the ETS”.

Advocates of the scheme also argue that the tighter caps imposed in Phase II will cause the price of carbon to increase and will incentivise industries to start implementing cleaner technologies and practices. Predictions of higher price permits in Phase II are somewhat optimistic in the face of the ‘linking directive’ which means that companies can also acquire credits by investing in Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects—that is, offset projects in the global South through the Kyoto protocol.

This ‘linking directive’ represents a serious ‘leak’ in the system that undermines the effectiveness of tightened caps. According to the same Climate Policy article, “some market participants anticipate that the European market could be flooded by these [CDM] allowances to such an extent that the EU allowance price would plummet”.

It is not only the availability of such cheap credits that undermine the climate credibility of the ETS. The nature of the CDM projects themselves have come under sustained criticism.

The CDM is framed in benevolent development rhetoric (the ‘D’ in the CDM). The projects are supposed to bring developmental benefits to local communities and the market was expected to create incentives for investment in low-carbon energy infrastructure in Southern countries. But almost two thirds of the 1,534 CDM projects in the pipeline as of early 2007 did not involve either the generation of clean energy or carbon dioxide emissions.

The largest share of CDM credits (30 per cent) has been generated by the destruction of HFC-23. This potent greenhouse gas is created by the manufacture of refrigerant gases. A study in the February 2007 article of Nature showed that the value of these credits at current carbon prices was €4.7 billion. Not only was this twice the value of the refrigerant gases themselves, but it was also estimated that the cost of implementing the necessary technology to capture and destroy the HFC-23 was less than €100 million, so something in the region of €4.6 billion was generated in profit for the owners of the plants and the project brokers.

This enormous sum of money generated by these Kyoto-style trading schemes has not gone to the companies and communities who are taking action on clean energy and energy reduction projects, but rather to big, industrial polluters who are then at liberty to reinvest the profits into the expansion of their operations. In the 2006/07 financial year, the owners of SRF, an industrial and textiles company based in India, reported a profit of €87 million from the sale of carbon credits derived from the destruction of HFC-23. Ashish Bharat Ram, the managing director, told the Economic Times that “Strong income from carbon trading strengthened us financially, and now we are expanding into areas related to our core strength of chemical and technical textiles business.”

Many of the corporate benefactors of CDM money in Southern countries are the target of sustained local resistance from communities who have to endure the often life-threatening impacts of intensive, industrial pollution. In 2005, about 10,000 people from social movements, community groups and civil society organisations mobilised in Chhattisgarh, India, to protest at the environmental public hearing held for the expansion of Jindal Steel and Power Limited (JSPL) sponge iron plants in the district. The production of sponge iron (an impure form of the metal) is notoriously dirty, and the companies involved have been accused of land-grabbing, as well as causing intensive air, soil and water pollution. JSPL runs the largest sponge-iron plant in the world, which is spread over 320 hectares on what used to be the thriving, agricultural village of Patrapali. This plant alone has four separate CDM projects, generating millions of tonnes of supposed carbon reductions that could be imported into the ETS. The inhabitants of three surrounding villages are resisting a proposed 20-billion-rupee expansion that would engulf them. The CDM is not only providing financial assistance to JSPL in making this expansion, but also providing them with green credibility in being at the forefront of the emerging carbon market.

The CDM may even act as a disincentive for Southern governments considering climate-friendly legislation. Had it been mandatory for factories to capture and destroy HFC-23, they would not have qualified for CDM status, as the carbon funding would not have been ‘additional’.

John Kay, a financial journalist, wrote in the Financial Times that, ‘when a market is created through political action rather than emerging spontaneously from the needs of buyers and sellers, business will seek to influence market design for commercial advantage’, and this is what we have seen at every step in the design and implementation of the various rounds of emissions trading, and this is what we have to look forward to in the future. The Wall Street Journal confirmed last March that emissions trading would make money for some very large corporations, but don’t believe for a minute that this charade would do much about global warming. The paper termed the carbon trade old-fashioned rent-seeking. making money by gaming the regulatory process.

Carbon trading is by no means the only show in town, but somehow we have been lead to believe it is this or nothing. There are a whole host of regulatory measures, legislative steps, community responses and lifestyles changes that could be made that do not involve trading schemes of any kind, and the market-mania of carbon trading is distraction attention from, and even actively hampering the deployment of real progress towards addressing the climate crisis. In the UK, a leaked document revealed that the government was considering stepping back from its targets to develop renewable energy infrastructure, partly because there was concerns that this measure was interfering with the smooth running of the emissions trading scheme!

The concept that underpins the whole system of carbon trading and offsetting is that a ton of carbon here is exactly the same as a ton of carbon there. That is, if its cheaper to reduce emissions in India than it is in the UK, then you can achieve the same climate benefit in a more cost-effective manner by making the reduction in India.

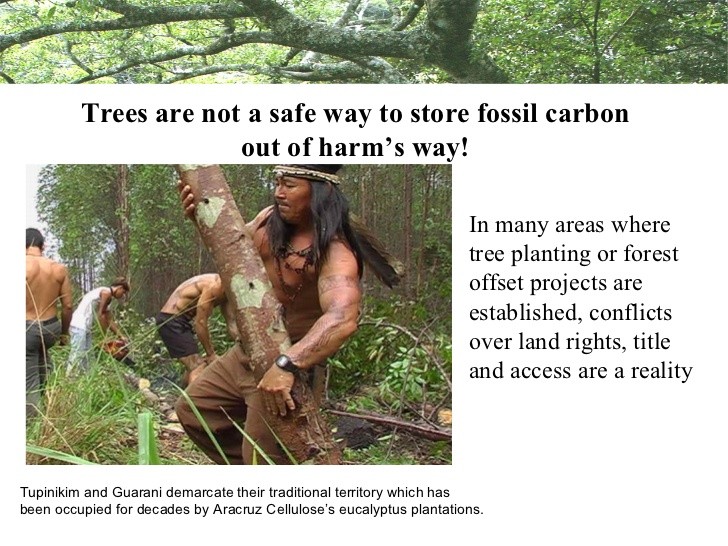

But, the seductive simplicity of this concept is based on collapsing a whole series of important considerations, such as land rights, North-South inequalities, local struggles, corporate power and colonial history, into the single question of cost-effectiveness. The mechanisms of emissions trading and offsetting represent a reductionist approach to climate change that negates complex variables in favour of cost-effectiveness.

So when the Dutch FACE Foundation plants trees in Kibale national park in Uganda to offset consumer flights, it ignores the fact that the land has been the site of violent evictions in the recent past and is still hotly contested by the people who once lived there. When companies buy carbon credits in the EU Emissions Trading scheme, the cheapness of the supposed emissions reductions is all that is important. But, any offsetting in Southern countries to justify emissions in Northern countries completely bypasses the issue of the extreme disparity in the levels of per capita carbon consumption and assumes that emissions reductions in the South can be treated like another colonial commodity to be extracted and traded.

Even within the cost-obsessed logic of the market, the use of carbon trading and offsetting goes against common sense. The point of the system is to provide opportunities for Northern companies to delay making the costly transition to low-carbon technologies. This is indeed, ‘cost effective’ in the short term, as its easier and cheaper to buy carbon credits rather than go about the complicated business of making those changes, but studies have shown time and again that the longer we delay making those changes, the more expensive and difficult it will be, in terms of society enmeshing itself even further in the web of fossil-fuel dependency, and of even more costly adaptation to the exacerbated impacts of climate change.

Waiting yet more years to learn further lessons from the next round of ineffective emissions trading is a luxury we don’t have. However politically unfashionable it may be, and however inimical it is to the business community, there is an urgent need to return to the tried and tested means that do deliver real results in terms of emissions reductions, such as stricter regulation, oversight and penalties for polluters on community, local, national and international levels, as well as support for communities adversely impacted by climate change.