The 2008 Oil Price Shock Markets or Mayhem

Post on: 6 Июль, 2015 No Comment

The 2008 Oil Price Shock: Markets or Mayhem?

James L. Smith

November 6, 2009

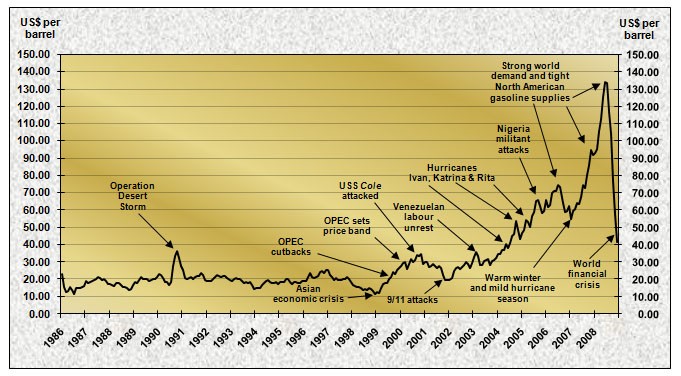

World oil prices rose from $50 per barrel in early 2007 to $140 per barrel in the summer of 2008, before falling to $40 per barrel by the end of that year. Can this dramatic price shock be explained by market fundamentals—shifts in worldwide demand and supply for oil—or were speculative forces at work?

20Photos/Energy%20and%20Climate/oil_drilling_silhouette_325.jpg /%

Why did oil prices spike in 2008, and what role (if any) did speculators play?

Perhaps a useful starting point is to observe that, while 2008 exhibits an extraordinarily large price swing, volatility in oil prices is ordinarily quite high because the underlying demand and supply curves are so inelastic. Demand is inelastic due to long lead times for altering the stock of fuel-consuming equipment. Supply is inelastic in the short term because it takes time to augment the productive capacity of oil fields. Price volatility provides incentives to hold inventories, but since inventories are costly they are not sufficient to fully offset the rigidity of supply and demand.

The steep ascent in the price of oil between 2004 and 2008 coincided with the first significant decrease in non-OPEC supply since 1973 and an unprecedented surge in global demand. Although OPEC members responded by increasing their production, they lacked sufficient capacity after years of restrained field investments to bridge the growing gap between global demand and non-OPEC supply.

Even seemingly small shocks may have large effects. Can they help explain the spike in oil prices in the first half of 2008? It was definitely a time of significant upheavals, some with the potential for sustained disruption of supplies. In February 2008 Venezuela cut off oil sales to ExxonMobil during a legal battle over nationalization of the company’s properties there. Production from Iraqi oil fields, of course, had still not recovered from wartime damage, and in late March saboteurs blew up the two main oil export pipelines in the south—cutting about 300,000 barrels per day from Iraqi exports. On April 25, Nigerian union workers went out on strike, causing ExxonMobil to shut in production of 780,000 barrels per day from three fields. Two days later, on April 27, Scottish oil workers walked off the job, leading to closure of the North Forties pipeline that carries about half of the United Kingdom’s North Sea oil production. As of May 1, about 1.36 million barrels per day of Nigerian production was shut in due to a combination of militant attacks on oil facilities, sabotage, and labor strife. At the same time, it was reported that Mexican oil exports (tenth largest in the world) had fallen sharply in April due to rapid decline in the country’s massive Cantarell oil field. On June 19, militant attacks in Nigeria caused Shell to shut in an additional 225,000 barrels per day. On June 20, just days before the price of oil reached its historic peak, Nigerian protesters blew up a pipeline that forced Chevron to shut in 125,000 barrels per day. Each of these events clearly registered in the spot market. It is not implausible to believe that, arriving in quick succession, they contributed heavily to the rapid acceleration in the spot price of oil.

Although the rising price of trend of 2004 to 2008 is consistent with changes in market fundamentals—surging demand and falling supply—the spectacular ascent especially in the first half of 2008 created widespread suspicion that “speculators” were responsible. But neither hedging nor speculation in the futures market exerts any significant effect on current (spot) oil prices. There are two main reasons: (1) due to the law of one price, the futures price must converge to the spot price as the expiration date draws near, and (2) virtually all futures contracts are settled for cash, which means that every futures contract purchased by a trader is subsequently sold by that same trader before the contract expires. Buying pressure is offset by selling pressure and no oil ever changes hands.

Finally, we might ask whether price fixing, rather than speculation per se, might be responsible for the dramatic increase in price. OPEC does engage in price fixing, and oil prices would not have reached $145 per barrel if OPEC had not previously restricted investment in new capacity. But OPEC did not actually take any positive action in 2007 or 2008 that precipitated the price spike. OPEC aside, there is no evidence of price fixing on the part of anyone else, which includes both speculators and the oil companies.