Risk in the Strategic Planning Process

Post on: 9 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Advertisement

The uncertainties of planning are well-documented in prose and poetry. The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry, wrote Robert Burns (in translation). When men speak of the future, the gods laugh, says a Chinese proverb. Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future, declared Niels Bohr. But you don’t have to be a philosopher to know that strategic planning is simultaneously important and daunting — and that planning for the future is no guarantee you’ll get the future you expect. It’s not unusual, in life or business, to invest a great deal of energy into a desired future state that simply doesn’t pan out.

While strategic planning has always been hard, it has been getting harder. According to Geoffrey Colvin’s October 2, 2006, Fortune article, Managing in Chaos, a recent study of S&P 500 companies showed that overall risk levels — risk to a company’s ability to achieve stable long-term earnings growth — has more than doubled since 1985. In that year, only 35 percent of the S&P 500 faced high risk and highly volatile long-term earnings growth. By 2006, that number had risen to 71 percent. During the same period, the number of companies enjoying low risk and volatility fell from 41 percent to 13 percent.

This rise of risk and uncertainty appears to be fueled by two major factors: speed and connectedness. In today’s technology-enabled business environment, conditions change rapidly, and organizations that don’t anticipate or respond in time can easily find themselves losing their competitive edge, market share, or worse. Furthermore, in a global, connected economy, changes or trends that occur in one industry or region can have a nearly instantaneous impact on companies in other industries and regions. In this environment, no company’s future is assured.

Failure: A Taboo Topic

Talk of failure is traditionally shunned in executive suites. The focus, instead, is placed on the upside of a company’s strategy and on the perceived need for unwavering commitment to execute that strategy. All too frequently, the brave (or foolhardy) individuals who question the viability of plans or raise the specter of risks are perceived as not being on the same page, or not being team players.

It’s high time that more organizations put failure on the table. Only by acknowledging and better understanding risks and uncertainties, as well as the key assumptions underlying their planning, can companies take the steps to manage their risks more effectively. And only by acknowledging the potential for failure can they understand and manage it. Consider, for example, a hedge fund that lacked adequate controls and bet heavily on its assumptions about low-probability risks. It did not monitor the effectiveness of its policies — or changes in its risk environment — and consequently went bankrupt. Similarly, domestic manufacturers that did not anticipate a change in consumer preferences lost billions when foreign competition filled the void. In both of these cases, enterprises with historically strong performance failed to imagine the prospect of failure and paid the price for that mistake.

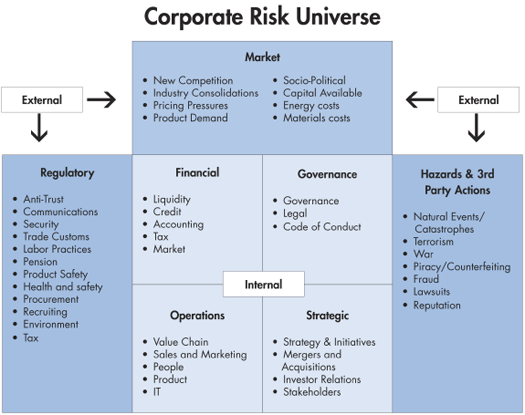

For businesses, the most common failure of imagination lies in not understanding or considering how the enterprise itself could fail to achieve and sustain revenue growth, how it could fail to improve its operating margins and the efficiency of its assets, or how it could fail to meet the expectations of its key stakeholders. Decision-makers who understand how the enterprise could fail can then decide whether to accept the risk of failure and figure out how best to prevent it, more readily detect it, and possibly correct it. A capacity to imagine and then prevent failure must be built into the strategic planning process. Organizations need to be intelligent about the risks they must take to gain and sustain competitive advantage (rewarded risks), as well as the risks they must avoid (unrewarded risks) to protect their existing assets (see Understanding Unrewarded vs. Rewarded Risk).

On Risk Intelligence

While most companies employ some form of enterprise risk management, only a minority are what we at Deloitte & Touche LLP would call Risk Intelligent Enterprises. Risk intelligence is the ability to think and learn about outcomes. It is how an organization gathers, analyzes, applies, and learns from information. Risk intelligence requires effective systems, accurate data, and timely reporting, but it enables organizations both to exploit strategic opportunities and to protect their existing assets.

Consider, for example, a company about to expand overseas. While emerging markets are brimming with opportunities, they are also fraught with risk. In many locations, these can include weak intellectual property (IP) protections, uncertain political environments, rampant corruption, and complex legal and regulatory regimes, to name but a few. Success in emerging markets requires an intelligent approach to managing the risks necessary for future growth while avoiding risks that have no upside potential. Based on a recently released Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Global Manufacturing study, Innovation in Emerging Markets, Risk Intelligent Enterprises keep their highest-value activities in more developed markets with better IP protections, while sourcing components and distributing production and data centers across multiple emerging markets. They also conduct rigorous and integrated risk assessments of supply chain, legal and regulatory tax, business continuity, intellectual property, security, and geopolitical risks before entering an emerging market. After entering a market, Risk Intelligent Enterprises perform risk assessments on a regular basis to catch early warnings of risk factors that may affect ongoing operations. As a result, Risk Intelligent Enterprises have higher confidence in their ability to manage risks.

Success demands excellent risk management as a core competency. Risk intelligence enables an organization to respond to rapidly changing circumstances with greater agility and resilience. Risk handled well becomes a source of competitive advantage; handled poorly, it can severely hamper a company’s prospects. The greater the risk, the less complacent an organization can afford to be.

Strategic Planning, Risk, and Decision Horizons

When it comes to risk-intelligent strategic planning, we have good news and bad news.

First, the good news. Although few organizations are where they want to be in terms of their risk intelligence, the work required to get there is not all new. Many midsize and large organizations are already working to align strategic planning with tactical and operational processes for budgeting and forecasting purposes. They can leverage this effort to better understand how various risks may affect their plans.

The bad news? In too many organizations, individuals who are responsible for strategic planning don’t have an integrated view of risk. The necessary intelligence may reside in specialist silos such as treasury, compliance, insurance, business continuity, operational risk, IT, internal audit, procurement, financial accounting, human resources, and engineering; as well as silos that represent distinct operational divisions within business units. This segregated intelligence is frequently not accessible to top-level decision-makers. In response, an increasing number of organizations are creating the position of chief risk officer to gain this portfolio view (but chief risk officers generally do not, it should be noted, actually manage the risks).

When organizations set out to incorporate risk considerations into the planning process, a range of time horizons must be taken into account. Specific business functions, for example, are focused on strategies one to three years out. Within a line of business, the time horizon extends to three to five years. At the corporate level, strategic planning stretches to five years or more. And at the board level, strategy should include the focus of the lower levels, in addition to being framed against a much longer time horizon — as far as 10 to 20 years into the future — to ensure shareholder value and the viability of the organization.

Uncertainty increases with each expanding time horizon. Managers generally have a higher degree of certainty, or confidence, about predictions for events that may happen in the next quarter or the next year. As they look further into the future, the degree of uncertainty grows dramatically. Moreover, as time horizons broaden, they demand a different perspective and different actions from decision-makers.

Line managers should direct their efforts to delivering on short-term commitments, and they should address operational, execution, and compliance risks. Their ability to plan and manage to key performance and risk indicators provides them with a timely means, as well as a clear responsibility, to escalate risks to others who need to know. At the next level, business unit leaders should concentrate on making tactical and strategic choices within the overall enterprise constraints and targets. The CEO should manage longer-term uncertainties, recognizing that this is where the company faces both the most opportunity and the most vulnerability. Finally, the board’s focus should be on the company’s strategic risk profile and overall business viability.

To help decision-makers at all levels better anticipate the future, a company needs an integrated decision-support framework that links key performance metrics with business and risk intelligence. In this way, existing business intelligence efforts can be leveraged with risk intelligence to support an integrated decision-support framework.

Daring To Ask What If?

Business plans typically focus on a desired future, and this desired future is underpinned by a set of reasonable assumptions. But each of these assumptions carries a level of uncertainty and risk. From a strategic perspective, it is crucial to have strategic flexibility and to identify a full range of possible futures — not just the most desirable. This can be accomplished through scenario planning activities that identify key assumptions and underlying drivers of change. Companies that don’t engage in rigorous scenario planning may fail to recognize when their fundamental business assumptions become invalid.

From the highest to the lowest levels of the organization, and across the entire span of time horizons, decision-makers must ask: What could cause us to fail? What would be the effects of that failure? How could this potential failure be prevented, detected, and corrected?

One of the best ways to integrate scenario planning into routine business operations is to piggyback it upon existing processes. Consider, for example, the case of a diversified manufacturer that used Six Sigma. When executive management and the board decided they needed to better understand the key risks to the enterprise, they chose to apply Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to their strategy and operational planning processes as a means to identify, on an ongoing basis, factors that might prevent the company from achieving its business objectives. The company also defined impact thresholds for each level of the enterprise, along with a set of escalation triggers. These thresholds determined how big a risk needed to be before it would get onto the board’s radar screen vs. executive management vs. line of business vs. a specific department or function.

The senior executives were already familiar with FMEA, and it took only minor modifications to adapt it to the entire enterprise. Now the analytical tool is part of every budgeting and planning process and quarterly review in this company. This manufacturer’s use of a common and readily understood tool greatly accelerated adoption of scenario planning throughout the organization.

By identifying the ways a function, a line of business, or the enterprise itself could fail, organizations can identify and assess previously unknown risks that could threaten strategic plans. What-if scenarios enable organizations to challenge their most basic assumptions, consider how resilient the organization might be when faced with those scenarios, and determine how agile the company must be should those basic assumptions change.

Far too frequently, when bad things happen, they happen much faster than anticipated and interact in unexpected ways. For example, when a recent undersea earthquake ruptured fiber-optic cables off the southern coast of Taiwan, a U.S. company’s communications with its suppliers in China and India were disrupted. Prior to the earthquake, the company hadn’t realized that it was exposed to this vulnerability. Consequently, the company is now developing a communications system across the Atlantic, as a backup to its current trans-Pacific system. By incorporating what-if scenarios into its regular strategic planning process, this company might have averted the substantial financial hardship the earthquake caused.

Toward Risk-Intelligent Strategic Planning

What will tomorrow’s customers want? What will competitors do? What unforeseen disasters, economic events, or legislative requirements will dominate the business environment? No one knows. Businesses do not plan or make decisions with perfect information; they manage with the best information that’s available. And in such uncertainty, no business can assume it is immune to failure. That’s why organizations should build in a systematic means of placing uncertainty at the core of strategic decision-making, looking at a wide range of causes and effects that could damage the company, and emboldening individuals to question assumptions at every level of the organization. Such an acknowledgement of risk does not make the enterprise risk-averse but makes it better prepared to deal with risk.

Consider a chemical company that wanted to better understand its sensitivity to a range of uncertainties. One of those uncertainties was a market downturn, which it saw as inevitable but unpredictable. The company incorporated into its strategic planning process an analysis of its sensitivity to price and volume decreases, commodity price fluctuations, technology shifts, competitive pressures, and supply chain disruptions. As a result of this analysis, the company determined that its cost structure would be uncompetitive. It migrated toward a cost structure that would provide more flexibility under a variety of scenarios.

The chemical company also determined that its product managers were acting in isolation, not sharing market information that could be valuable to others or could provide early warning of a market downturn, customer credit weakness, and vendor vulnerabilities. Market information was being collected on an ad hoc basis by each of the product groups, which required significant individual effort and resulted in inconsistency and inefficiency, as well as limited or nonexistent intelligence sharing. The company took actions to improve information sharing, including systematically collecting and distributing external market information that was common to all product groups, reactivating a cross-product group managers meeting, identifying and sharing internal performance information through improved reporting and use of dashboards prepared by the IT group, and undertaking a cost restructuring program to improve resilience and flexibility to adapt quickly to a variety of favorable and negative market scenarios.

Over the long term, organizations that are able to see strategic planning in the context of risk, as this chemical company does, and that are able to incorporate a risk-intelligent perspective into their planning processes, will be most adept at managing risks and achieving sustained success.

Understanding Unrewarded Vs. Rewarded Risk

Risk comes in two flavors: unrewarded and rewarded.

Failure to comply with payroll tax withholding and related reporting laws can have consequences, but there’s no extra credit for being exceptionally compliant. Similarly, it’s important to avoid disruptions to critical operations and systems, but doing so doesn’t earn a premium from investors; it simply meets their expectations. These types of risks are unrewarded risks. They can’t be ignored, but the primary incentive for tackling them is value protection.

The area of unrewarded risks has been the traditional domain of a few specialists in areas such as compliance, Sarbanes-Oxley, insurance, security, and internal audit. These functions are often removed from the mainstream of the business, and their job is seen as protecting the company’s existing assets so that executives can focus on the growth agenda (the real business).

Rewarded risks, on the other hand, are all about defining and delivering the upside — strategies to introduce new innovations or expand into new markets, for example. The primary impetus for taking rewarded risks is value creation. At the strategic level of the enterprise, rewarded risks are the domain of executive management and the board.

Risk-intelligent companies embed both rewarded and unrewarded risks deep within the corporate planning process.

Bob Ruprecht is a partner in the enterprise risk services group of Deloitte & Touche LLP. He can be reached at rruprecht@deloitte.com .