Restricting Speculators Will Not Reduce Oil Prices

Post on: 8 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Craig Pirrong

Updated July 11, 2008 11:59 p.m. ET

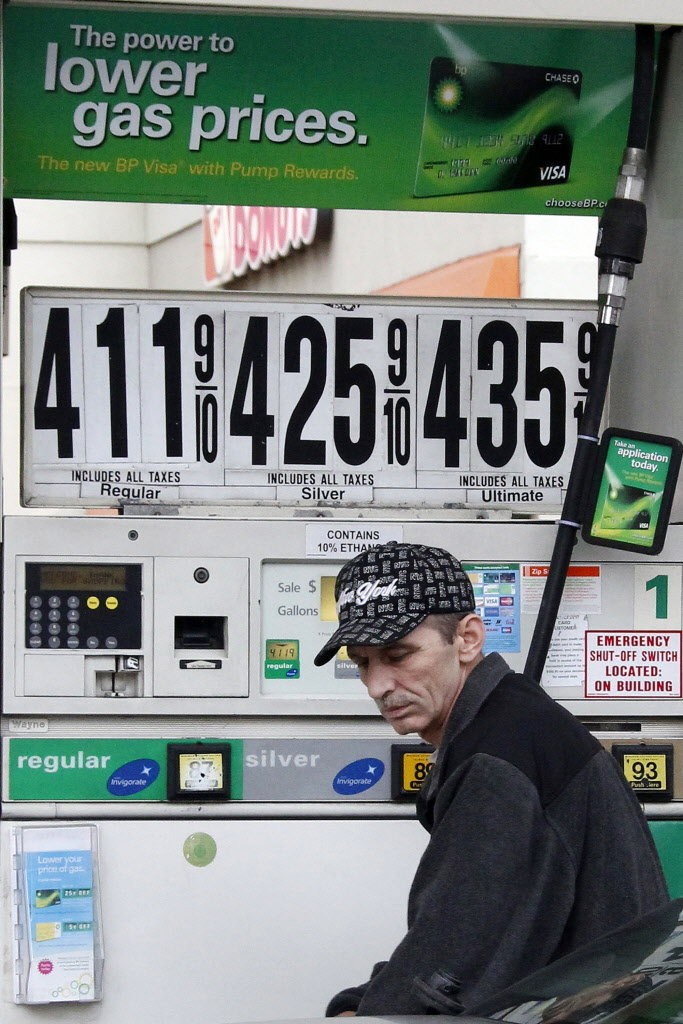

Commodity price shocks, like those currently rocking the oil market, inevitably lead to witch hunts. And speculators are typically among the first to be hunted down.

Many in Congress — including Sen. Joseph Lieberman (D. Conn.) and Rep. Bart Stupak (D. Mich.) — assert that oil market trading by financial institutions and investment funds has added as much as $70 per barrel to the price of oil. These charges are echoed by myriad others, including financier George Soros and Fox News personality Bill O’Reilly.

Mr. Lieberman wants to ban any pension fund or financial institution with more than $500 million in assets from participating in the futures markets. He also proposes limiting investment banks’ positions in futures-like swap contracts traded in the over-the-counter market.

Mr. Stupak, for his part, has introduced The Prevent Unfair Manipulation of Prices Act. He reportedly accused Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley of manipulating the markets — though he disclaimed knowledge of evidence of illegal behavior, and subsequently complained that he was misquoted.

But the wild assertions about speculation and manipulation are defective, and completely unsupported by reliable evidence. The proposals by Messrs. Stupak and Lieberman, not to mention others ricocheting around Capitol Hill, would not reduce prices. They would harm consumers and producers.

First, consider the charge that commodity prices are being manipulated. There are of course certain well-known forms of market manipulation — notably the corner or squeeze. Here a trader buys more futures contracts than there is commodity to deliver, and forces those that have sold to him — but who cannot deliver — to buy back their contacts at an exorbitant price. None of this has been observed in the oil markets in recent months. Even more to the point, manipulations of this sort typically have short-lived effects on prices. They cannot account for the extended run of high oil prices.

What about the impact of speculation more generally? The assertion here is that noncommercial market participants have increased their positions in these markets both absolutely, and as a fraction of the total number of contracts outstanding; that these speculators are buyers on net; that this speculative buying has increased by about as much as the increase in Chinese oil demand over the past five years; and therefore, that speculators have driven up demand for oil, and its price.

This argument represents a complete misunderstanding of futures markets.

For the most part, speculators do not demand physical oil the way thirsty Chinese refiners do. There is no evidence that speculators are accumulating large and rising inventories of physical oil. But to cause prices to be above their competitive level, speculators would have to take physical oil off the market — the way that governments have done in the past with agricultural products, amassing mountains of grain and cheese to prop up their prices.

What some speculators do instead is trade futures contracts that entitle them to take delivery of physical oil at a future date (say next August) at a price negotiated in the marketplace. But they almost never exercise the right to take delivery when the contract matures.

A speculator who anticipates rising prices buys a futures contract at the prevailing market price. If he is right, and the futures price rises, he can sell the contract at the higher price before contract maturity and pocket a profit; if he is wrong, and prices fall, he sells the contract at a loss. Buyers and sellers of these futures contracts almost never take delivery of the oil to implement their trading strategies.

Restricting these speculators won’t reduce the price of oil — but they are likely to make consumers and investors worse off. Futures and swap markets facilitate the efficient management of price risks, and speculators are an important part of that process. For instance, a producer of oil may want to lock in the price at which he sells his oil in the coming months in order to hedge against fluctuations in its price. He can do so by selling a futures contract at the prevailing market price. Similarly, an airline can protect itself against price increases next summer by buying today a futures contract that locks in a purchase price for next July.

Producers and consumers who want to hedge in this fashion cannot wave a magic wand to make the price risks they face disappear. The oil producer has to find somebody to sell to, and the airline must find somebody to buy from — and that somebody is often a speculator. Restricting speculation would increase the costs that producers, consumers (such as airlines), and marketers (such as heating-oil dealers) pay to manage their price risks by reducing the number of traders able to absorb the risks they want to shed.

These higher risk management costs would result in higher prices at the pump or the airline ticket counter for consumers, and less investment in new productive capacity — which would keep prices high into the future.

Participation in these oil markets by pension funds and other investors (a la Mr. Lieberman) is also not a problem. By adding commodity futures to their portfolios, i.e. by diversifying, these investors can reduce their risks without sacrificing returns, and without impacting physical inventories (or prices). Consumers are the ultimate winners when risks are borne as efficiently as possible in these markets.

The unprecedented run-up in oil prices is painful for consumers around the world. But the focus on speculation is misguided, and represents a convenient distraction from an understanding of the real, underlying causes of high oil prices — most notably continuing demand growth in the face of stagnant production, supply disruptions and the weakening dollar.

More restrictions and regulations of energy markets, in the vain belief that such actions will bring price relief, are counterproductive. They will make the energy markets less efficient, rather than more so.

Mr. Pirrong is professor of finance at the University of Houston.

See all of today’s editorials and op-eds, plus video commentary, on Opinion Journal .