More speculation about those oil speculators

Post on: 8 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

I normally leave it to folks like Dean Baker to beat up on the press. But I cant resist shining a bright light on todays story about oil speculators in the Washington Post. which has also been discussed by Mark Thoma and Tyler Cowen .

David Cho opens his story in the Washington Post with this bombshell:

Regulators had long classified a private Swiss energy conglomerate called Vitol as a trader that primarily helped industrial firms that needed oil to run their businesses.

But when the Commodity Futures Trading Commission examined Vitols books last month, it found that the firm was in fact more of a speculator, holding oil contracts as a profit-making investment rather than a means of lining up the actual delivery of fuel.

Lets start with some background. The CFTC issues a report each week that summarizes the number of open futures contracts in oil and a number of other commodity markets. The CFTC separates the holders of those contracts into three broad categories commercial, noncommercial, and nonreportable. Commercial traders are those who

report to the CFTC that they are

engaged in business activities hedged by the use of the futures or option markets.

So, for example, if your company has significant fuel costs, you would quite reasonably satisfy that definition of a commercial trader, regardless of whether the particular futures contracts you buy or sell this month are intended to hedge those costs. The CFTC specifically says further that it would classify as a commercial trader

a swap dealer holding long futures positions to hedge a short commodity index exposure opposite institutional traders, such as pension funds.

To an economist, any conceptual distinction between hedging and speculation is inherently problematic. When an oil refiner takes a position with futures contracts, it is unlikely to be ignoring its own guess as to where prices are heading. But making a bet based on such guesses seems to be the definition many people have in mind when they speak of speculation. On the other hand, when a pension fund manager takes a modest long position in commodities, that can reduce the overall variance of the portfolio due to the negative correlations between commodity price changes and other asset returns, which would most naturally be described as hedging against inflation risk. The idea that the motives of a given trader can always be classified as either pure hedging or pure speculation, and that the positions of commercial versus noncommercial traders reported by the CFTC give us meaningful information about those motives, strikes me as a very dubious proposition. Discovering a potential misclassification could hardly be the basis for becoming legitimately alarmed.

What else does Cho dig up? The article continues:

Even more surprising to the commodities markets was the massive size of Vitols portfolio at one point in July, the firm held 11 percent of all the oil contracts on the regulated New York Mercantile Exchange.

That does sound like a lot, though enough details are left out to make me wonder what is actually being claimed here. Surely Cho doesnt literally mean all the oil contracts, i.e. light sweet, Brent, heating oil, gasoline, and so on. If light sweet alone, are we talking about just futures, or futures plus options? Or is Cho possibly referring just to one very specific contract, such as the August CL futures contract? And were these positions held outright by Vitol or purchased on behalf of its clients?

Cho gets more quantitative a few paragraphs down:

By June 6, for instance, Vitol had acquired a huge holding in oil contracts, betting prices would rise. The contracts were equal to 57.7 million barrels of oil about three times the amount the United States consumes daily.

Again Id like to know if were including options somehow in this number. But more importantly, the claim that you can compare the number of notional barrels of oil implied by a futures contract if it were held to settlement with the number of physical barrels that the U.S. consumes repeats the egregious error committed by Michael Masters in his Senate testimony this May. You cant compare the outstanding NYMEX open interest with U.S. daily petroleum consumption numbers directly because they are measured in different units. Open interest is a stock it is measured in number of outstanding contracts at a particular point in time. Consumption is a flow it is measured in barrels per unit of time. You cant measure how many barrels of oil the U.S. consumes without specifying a time unit. We consume about 20 million barrels per day, or 14,000 barrels per minute, or 7.3 billion barrels per year. With which of these 3 numbers are we supposed to compare 57 million? Fifty-seven million sounds like a lot more than 14,000, and a lot less than 7.3 billion. You can make 57 million sound as big or as small compared with U.S. consumption as you want, because theres an arbitrary time interval associated with consumption that is not associated with open interest. If you want the futures volume to sound big, you compare open interest with daily consumption, as Masters and Cho both do.

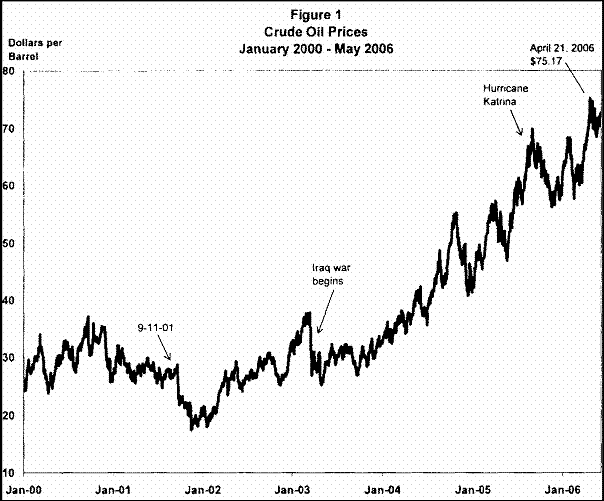

Cho was trying the best he could to convince us that unregulated speculation was the cause of this summers spike in oil prices.

But instead he convinces me that he really couldnt find much of a case.