Will The Readmission Rate Penalties Drive Hospital Behavior Changes Health Affairs Blog

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Will The Readmission Rate Penalties Drive Hospital Behavior Changes?

Since the development of the metric in 1984 by Anderson and Steinberg. inpatient hospital readmission rates have been used as a marker for hospital quality. A good deal of attention is now being paid to the new readmission rate penalties in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

While the penalties have garnered significant attention, it is unknown whether they will materially change hospital behavior. In this post, after reviewing the mechanics of the penalties, we take a close look at how they are likely to affect hospital incentives. We also suggest some refinements to the penalties that could help achieve the aim of reducing preventable readmissions.

How The Penalties Work

The readmission penalty in the ACA is based on readmissions for three conditions: Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Heart Failure, and Community Acquired Pneumonia. For each hospital, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) calculates the risk-adjusted actual and expected readmission rates for each of these conditions. Risk-adjustment variables include demographic, disease-specific, and comorbidity factors. The excess readmission ratio is the actual rate divided by the expected rate.

Simplifying a little, the aggregate payments for excess readmissions is summed for all three conditions over the past three years, then divided by total base operating DRG payments for the past three years to calculate the penalty percentage. Base operating DRG payments are IPPS payment less DSH, IME and outliers except for new technology. The total penalty is the penalty percentage times total base operating DRG payments for that fiscal year, provided that the total amount does not exceed 1 percent of base operating DRG payments in fiscal year 2013, a cap that increases to 3 percent in fiscal year 2015.

According to calculations by CMS, the overall penalty in 2013 is likely to be 0.3 percent of inpatient reimbursements, or $280 million, with 8.8 percent of hospitals receiving the maximum penalty.

Changes in hospital performance are predicated on these values being significant for hospitals. The natural benchmark to the penalties that providers face is the amount that hospitals earn from potentially avoidable readmissions. Readmissions in 2010 were estimated by CMS to cost Medicare $17.5 billion. Studies suggest the avoidable portion of total readmissions ranges from 5 percent to 79 percent, with the median being 27.1 percent.

Multiplying the excess readmission rate by the average hospital inpatient EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) margin of 2 percent suggests that the current profit from readmissions above the avoidable portion is about $95 million. Thus, the penalties appear to be greater than the profits. This will be increasingly true in the future as Medicare moves to more bundled payments for acute care or global payments on a patient basis. In such a payment system, there will be no profits for readmission, so the only financial consequence for the hospital will be the penalty.

Of course, behavior change is not binary changes will happen along a spectrum. Consider the fixed and variable costs for a hospital to address readmission rates. There are many fixed costs in reducing readmissions, including the need for electronic medical records (EMR), adding non-fungible labor for case management and discharge planning, and training employees in discharge planning. If the penalty on the hospital is high enough, the fixed cost inertia can be overcome. Related, legislation is helping to reduce the size of these fixed costs by incentivizing investment in EMRs.

For a hospital that has overcome the fixed costs, there are also variable costs necessary for reducing readmissions. These may include more nursing time per admission, additional supplies and post-discharge medications, and care coordination costs. Variable costs are potentially offset if beds are filled by another admission that generates higher margins.

Refining The Penalties

The interplay of the fixed and variable cost factors suggests that movement for hospitals will not start until the fixed cost is overcome, but once that threshold is surpassed, those readmissions most easily prevented will be taken out of the system. Rapid downward movement will then slow, as the net benefit shrinks for each patient. These types of costs suggest a policy modification of the economic incentives in the future: a sliding scale based on the number of readmissions to make each additional readmission increasingly more expensive.

Another important component of the readmission calculation is risk adjustment. Currently, the risk adjustment in the CMS penalty program includes only two demographic factors: age and gender. But studies suggest that higher readmission rates are linked with race and location. If we assume that lower-income populations face higher readmissions for reasons that are harder to prevent, the penalty will disproportionally affect hospitals that cannot realistically match their expected readmission rate.

To estimate the magnitude of this effect, we assumed that the readmission rate difference of 3.5 percentage points between minority and non-minority hospitals was purely structural. If a hospital which would otherwise be at the national average faces this type of difference, the calculated penalty would be 18 percent of revenue for those admissions. This would be inequitable and likely ineffective in reducing readmission rates, since it is targeting those readmissions that are unavoidable.

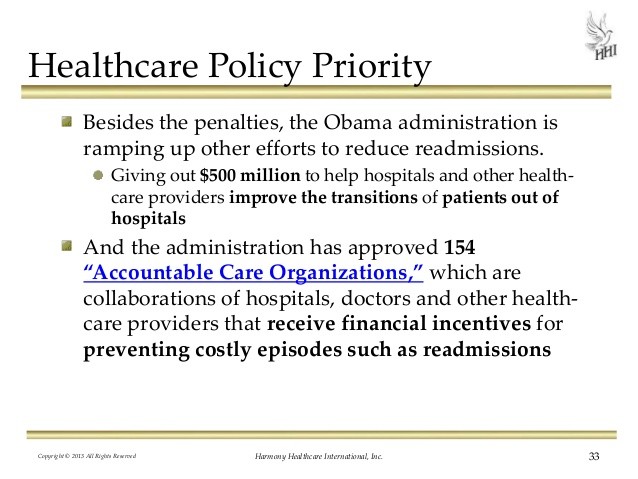

The extent to which hospitals reduce readmissions will depend on other factors as well. The organizational structure of the hospital for example, whether it is part of an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) and who leads the organization could matter a great deal. The fixed-cost base is much higher for hospital-owned ACOs than for physician-owned ACOs; parts of a hospital cannot be shut down, even if the bed is not filled. For this reason, hospital-owned ACOs may be less focused on readmission rate reductions in the short run, but more focused over time as they make capital allocation decisions.

Public perception, through increased transparency by efforts like Hospital Compare, may also push hospitals to change behavior. Studies show that hospitals have been shamed into improving mortality rates when they become measured.

In all, the new readmission penalty holds a good deal of promise. But to maximize benefits to patients, cost savings, and rate of improvement, future refinements are needed to better align incentives and adjust for more patient characteristics.

Editors note: The fourth paragraph of this post was edited to reflect the question from Austin Frakt and response by Nikhil Sahni in the comments section.

Don’t miss the insightful policy recommendations and thought-provoking research findings published in Health Affairs.