The Subprime Color Line

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Rich people don’t particularly mind talk about helping poor people — unless that talk starts linking the wealth of the one to the poverty of the other. Suggest that link and the cheerleaders for grand fortunes go apoplectic. How dare you intimate, they will huff, that the wealthy get wealthier by exploiting the poor!

This sort of bombast can be intimidating. But we can’t let ourselves be intimidated, not if we want to understand how our society really operates. Some phenomena that impact our lives, we need to remember, simply make no sense unless we contemplate the ongoing interplay between rich and poor.

Take, for instance, the mess around subprime mortgages.

That’s just what United for a Fair Economy has done inForeclosed: State of the Dream 2008 . this Boston-based group’s latest annual analysis of how fares the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

This newest State of the Dream zeroes in on the subprime crisis for a single powerful reason. This subprime lending debacle, as the report bluntly puts it, has caused the greatest loss of wealth to people of color in modern U.S. history.

And this awesome loss of wealth to people of color, Foreclosed patiently details, has its roots in the reckless behavior of people in power suits — from mortgage brokers and bank executives to Wall Street underwriters and hedge fund managers.

These players created a financial house of cards that offered fabulous rewards for turning a mortgage tool intended to be used sparingly and discerningly to help people with poor credit into a ruthlessly hawked con game disproportionately and systematically aimed at people of color.

All this unfolded virtually overnight. In 1994, subprime lending — the making of high-interest loans to households considered too risky for conventional mortgages — amounted to a mere $35 billion market. By 2005, subprime mortgages had become a $665 billion bonanza.

In 1998, only one out of every 10 new mortgages ranked as a subprime. By 2006, nearly a quarter of all new mortgages would be subprimes.

What drove the demand for these subprime loans? Above all else, inequality. The vast transfer of income and wealth up the American economic ladder since the 1970s, Foreclosed relates, had left working households with stagnating incomes — and affordable housing in short supply. Developers were too busy building mansions to worry about ordinary families.

The higher profit margins that come with building expensive homes, Foreclosed points out, have made the affordable housing market less attractive for private home development companies.

In deeply unequal early 21st century America, no new affordable Levittowns would arise to offer working families entry into the middle class. Instead, mortgage brokers steered families into high-interest, high-commission subprime loans. The more they steered, the more they raked in.

But the raking — note Foreclosed authors Amaad Rivera, Brenda Cotto-Escalera, Anisha Desai, Jeannette Huezo, and Dedrick Muhammad — went far beyond the brokers.

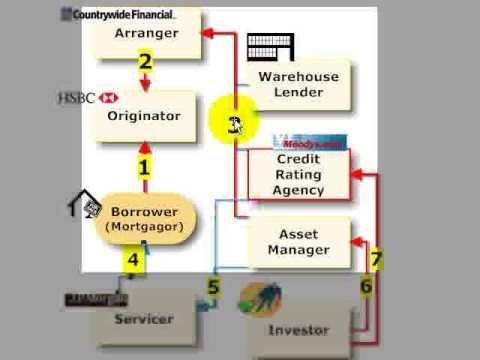

Banks and other finance firms securitized the subprime loans. They bundled them up into high-yielding investments for hedge funds and the like, creating, in the process, powerful incentives to cajole — by any means necessary — still more families into taking out subprime loans. The financial industry’s great subprime money-making machine needed to be fed.

Foreclosed introduces us to the tricks of the subprime trade: the pre-payment penalties, the teaser rates, the interest-only loans, and, most of all, the calculated targeting of asset-poor communities whose members were eager to acquire homes.

In most cases, these would be communities of color. Almost half of all African-American households with mortgages, Foreclosed notes, now hold subprime loans.

Huge numbers of these loans have already — or will soon — go bad, a turn of events that’s leaving homes vacated and neighborhoods ravaged, tax bases eroded and municipal budgets decimated. Communities are suffering. And the power suits?

Big banks on Wall Street are writing off billions in bad loans. Some executives have lost their jobs. But they’re exiting their suites with billfolds flush.

Former Citigroup CEO Charles Prince, for one, walked off with a package valued at over $29 million. At Merrill Lynch, chief executive E. Stanley O’Neal departed with $161 million.

Angelo Mozilo, the CEO of Countrywide Financial, will take away $115 million in severance from the subprime debacle. That’s on top of the $650 million Mozilo has pocketed over the past decade.

So what can be done? Back in the middle of the 20th century, Foreclosed reminds us, the United States taxed the rich — at rates well over double today’s rates — to help fund programs that offered families safe, low-cost home loans.

Those families would be overwhelmingly white. The great wealth-building programs that created the modern American middle class all discriminated, directly or indirectly, against African-American households, and since the end of legal segregation, Foreclosed bserves, we have not seen any comparable federal mass investment in homeownership that would benefit disenfranchised people of color.

Foreclosed proposes a variety of new programs — funded by higher taxes on the wealthy — that could remedy this historic deficit.

Wealth taxation and wealth development, says the report, need one another.

The challenge facing our nation, Foreclosed sums up, is not a lack of wealth but a destructive distribution of wealth. Over the last 40 years, the U.S. economy has shifted from one that was producing a strong middle class, to an economy that serves the richest among us almost exclusively and concentrates wealth among the wealthiest in society.

To fix the subprime mess, Foreclosed helps us understand, we need to concentrate on ending that concentration.