The MortgageBacked Securities Mess

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By Peter J. Henning October 22, 2010 10:00 am October 22, 2010 10:00 am

Peter J. Henning follows issues involving securities law and white-collar crime for DealBook’s White Collar Watch .

While much of the focus lately has been on problems with home foreclosures, the greater threat to financial firms like Bank of America is likely to come from potential liabilities related to billions of dollars of mortgage-backed securities. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York and others are trying to force banks to buy back problem mortgage loans, and Bank of America has vowed to fight demands to take back loans that were not underwritten properly.

About White Collar Watch

Peter J. Henning, writing for DealBook’s White Collar Watch, is a commentator on white-collar crime and litigation. A former lawyer at the Securities and Exchange Commission’s enforcement division and then a prosecutor at the Justice Department, he is a professor at the Wayne State University Law School. He is currently working on a book, “The Prosecution and Defense of Public Corruption: The Law & Legal Strategies,” to be published by Oxford University Press.

Mary L. Schapiro. the chairwoman of the S.E.C. said earlier this week that “whenever there are suggestions that there may have been any kinds of issues with respect to disclosure, misrepresentations or omissions, we are always looking at that kind of conduct.” That means disclosures that companies made to their own shareholders will be looked at, as well as what was said about the value of the loans packaged into mortgage-backed securities that the banks sold to various investors.

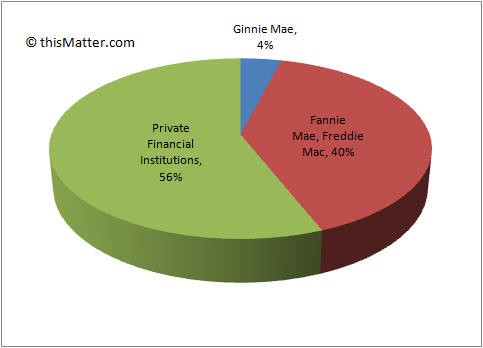

The mortgage-backed securities market was transformed from a small niche in the bond market into a trillion-dollar sector as companies like Countrywide Financial . later acquired by Bank of America, generated huge numbers of home loans that were quickly packaged and sold to investors to fund even more loans. When the housing market started collapsing in 2007, so too did the value of the securities sold, as more loans went into default and the terms of a number of mortgages were modified to avoid foreclosing on properties.

Some investors have challenged these mortgage modifications, which reduced the value of the mortgages in a securitized pool, by trying to force the lenders to take back the loans at full value.

Unfortunately, the servicing agreements for the mortgage-backed securities, often made by the banks that issued the securities, are quite protective of the issuer no great surprise there and provide few means for investors to challenge decisions that affect the pool of loans underlying their investments.

A recent decision from the New York State Supreme Court in a case that Greenwich Financial Services brought against Countrywide highlights how the roadblocks put in place in these servicing agreements prevent investors from suing the lender that put together the mortgage-backed securities. The court dismissed Greenwich Financials lawsuit, which sought to force Bank of America to buy back any mortgages that had been modified because mortgage modifications that reduced loan payments undermined the value of the securities.

Under the servicing agreement, an investor can sue for a breach of contract only if it has the voting rights to 25 percent of the securities in the trust created to hold the mortgage loans, and the New York court rejected the plaintiff’s argument that its complaint was in reality a class-action on behalf of all owners of the securities, so it did not need to meet the 25 percent threshold.

The S.E.C. will not face the same hurdle if it determines that an issuer of mortgage-backed securities misled investors about the risks or did not fully disclose potential problems if loans could not successfully go into foreclosure and the properties seized. An investigation of the banks that issued these securities could take months and involve millions of records, with the possibility that the S.E.C. would seek monetary penalties if it finds investors were misled.

The S.E.C. has already sued Goldman Sachs for its disclosures related to a fairly esoteric derivative security, and that case may provide a template for the types of case that the commission may pursue for banks that it accuses of misleading mortgage-backed securities investors even sophisticated ones about the risks from foreclosure problems and obligations to take back loans that were improperly issued.

An S.E.C. investigation may also send a signal to plaintiffs lawyers to consider pursuing private securities fraud class-actions on behalf of investors in the mortgage-backed securities. Although the servicing agreements limit the ability to file lawsuits alleging breach of contract, they would not limit the right of an investor to sue issuers and underwriters of the securities for fraud or misstatements in connection with the sales.

The main antifraud provision of the federal securities laws, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, applies to the sale of any security, and the right to pursue a remedy cannot be eliminated by a contract between the buyer and seller. In addition, some investors may be able to file claims under Sections 11 and 12(a)(2) of the Securities Act of 1933 for misstatements or omissions if a registration statement and prospectus were used in connection with the sale of the mortgage-backed securities.

One problem that investors may face in pursuing a private remedy is avoiding the statute of limitations for their securities claims. For a suit under Section 10(b), they have two years from discovery of the fraud or five years from when it occurred to file their claim, while Sections 11 and 12(a)(2) claims must be brought within one year of discovery and three years of the securities filing. This could limit claims to securities issued in just the last two years or so before the mortgage-backed securities market froze up, although any suits would still involve billions of dollars of securities.

There seems to be the potential for an almost unimaginable amount of litigation arising from the fallout from the collapse of the housing market. The problems with documents in foreclosure proceedings and the attendant government investigations may be just the tip of the iceberg if the S.E.C. finds misstatements and omissions were made in the issuance of mortgage-backed securities and investors pursue fraud claims against the banks that pooled mortgages and peddled them to investors.

Peter J. Henning