Information Technology and Productivity

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Table 5: Firm-Level Studies: Services.	19

Table 7: Growth Rates of Aggregate Output and Contribution of Factors	25

Table 8: Studies on Contribution to Consumer Surplus and Economic Growth.	27

I. The Productivity Paradox—A Clash of Expectations and Statistics

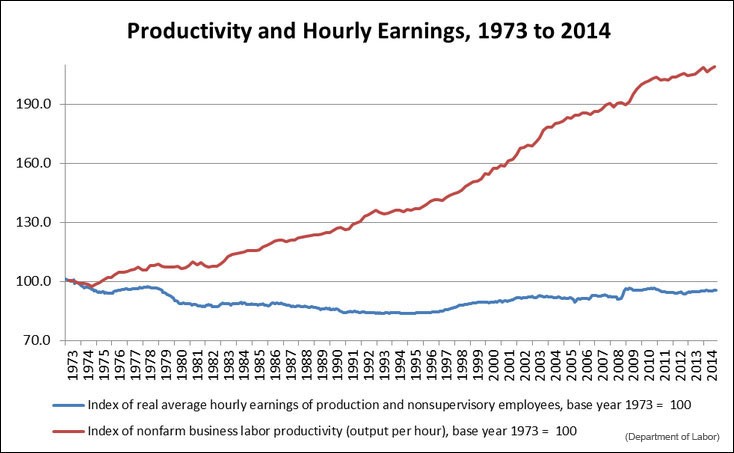

Over the past decade, both academics and the business press have periodically revisited the so-called productivity paradox of computers. On one hand, delivered computing-power in the US economy has increased by more than two orders of magnitude in the past two decades (figure 1). On the other hand, productivity, especially in the service sector, seems to have stagnated (figure 2). Despite the enormous promise of information technology (IT) to effect the biggest technological revolution men have known [Snow, 1966], disillusionment and even frustration with the technology are evident in statements like No, computers do not boost productivity, at least not most of the time [Economist, 1990] and headlines like Computer Data Overload Limits Productivity Gains [Zachary, 1991].

Interest in the productivity paradox, as it has become known, has engendered a significant amount of research. Although researchers analyzed statistics extensively, they found little evidence that information technology significantly increased productivity in the 1970s and 1980s. The results were aptly characterized by Robert Solow’s quip that you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics, and Bakos and Kemerer’s [1992] summation that, These studies have fueled a controversial debate, primarily because they have failed to document substantial productivity improvements attributable to information technology investments.

Now, after researchers such as Brynjolfsson and Hitt [1993, 1995], and Lichtenberg [1995] found firm-level evidence that IT investments earned substantial returns, the media pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Businessweek ’s proclamation of the productivity surge due to information technology, and Fortune magazine’s headline heralding the arrival of technology payoff represent the latest trend.

A growing number of academic studies also report positive effects of information technology on various measures of economic performance. As more research is conducted, we are gradually developing a clearer picture of the relationship between IT and productivity. However, productivity measurement isn’t an exact science. Our tools are still blunt, and our conclusions not as definitive as we would like. While one study shows a negative correlation between total factor productivity and high share of high-tech capital formation during 1968-1986 period [Berndt and Morrison, 1995], another study suggests that computer capital contributes to growth more than ordinary capital during the similar period [Jorgenson and Stiroh, 1995]. Hitt and Brynjolfsson [1994] report positive effects of IT based on output and consumer surplus measures. On the other hand, Landauer [1995] de-emphasizes the findings of recent studies and documents various cases of the trouble with computers. At this stage, the academic research results are inconsistent on a number of dimensions, including measures of performance, methodologies, and data sources.

Just as the business media’s premature announcement of a productivity paradox was out of proportion to the more carefully worded academic research, the current cover stories on the productivity payoff often overstate reality and overlook the limitations of the academic studies on which they were based. Although progress in this area of research has been quite substantial, a consensus about the relationship between IT investment and economic performance eludes us. More than a decade ago, one of the earliest surveys concluded that we still had much to learn about measuring the effects of computers on organizations [Attewell and Rule, 1984]. A more recent survey also reports a sobering conclusion: our understanding of how information technology affects productivity either at the level of the firm or for the economy as a whole is extremely limited [Wilson, 1995].

This paper seeks to contribute to the research effort by summarizing what we know and don’t know, by distinguishing the central issues from peripheral ones, and by clarifying the questions to be profitably explored in future research. Results and implications of different studies should be interpreted in the context of specific research questions. The question of aggregate economic performance differs from the question of firm-level economic performance. Data sources, and performance measures may also depend on the level of aggregation. Even within the same level of aggregation, results may depend on different measures of performance or research methods. While this review emphasizes economic approaches to both theory and empirics, it is hoped that the process of reviewing studies of the productivity controversy will serve as a useful springboard for examining other methodologies and the broader issues involved.

As a prelude to the literature survey, it is useful to define some of the terms used and to highlight some of the basic trends in the economics of IT.

Definitions:

• Information technology can be defined in various ways. Among the most common is the BEA’s (U.S. Bureau of Economics Analysis) category Office, Computing and Accounting Machinery (OCAM) which consists primarily of computers. Some researchers looks specifically at computer capital, while others consider the BEA’s broader category, Information Processing Equipment (IPE). IPE includes communications equipment, scientific and engineering instruments, photocopiers and related equipment. Besides, software and related services are sometimes included in the IT capital. Recent studies often examine the productivity of information systems staff, or of workers who use computers at work.

• Labor productivity is calculated as the level of output divided by a given level of labor input. Multifactor productivity (sometimes more ambitiously called total factor productivity) is calculated as the level of output for a given level of several inputs, typically labor, capital and materials. In principle, multifactor productivity is a better measure of a firm or industry’s efficiency because it adjusts for shifts among inputs, such as an increase in capital intensity. However, lack of data often renders this consideration moot.

• In productivity calculations, output is defined as the number of units produced times their unit value, proxied by their real price. Determining the real price of a good or service requires the calculation of individual price deflators, often using hedonic methods, to eliminate the effects of inflation without ignoring quality changes.

Trends:

• The price of computing has dropped by half every 2-3 years (figure 3a and figure 3b). If progress in the rest of the economy had matched progress in the computer sector, a Cadillac would cost $5.91, while ten minutes’ labor would buy a year’s worth of groceries.

• There have been increasing levels of business investment in information technology equipment. These investments now account for over 10% of new investment in capital equipment by American firms (figure 4, table 2).

• Information processing continues to be the principal task undertaken by America’s work force. Over half the labor force is employed in information-handling activities (figure 5).

• Overall productivity has slowed significantly since the early 1970s and measured productivity growth has fallen especially sharply in the service sectors, which account for 80% of IT investment (figure 2, table 4). However, there is some evidence of a rebound more recently.

• White collar productivity statistics have been essentially stagnant for 20 years (figure 6).

These trends suggest the two central questions which comprise the productivity paradox: 1) Why would companies invest so heavily in information technology if it didn’t add to productivity? 2) If information technology is contributing to productivity, why is it so difficult to measure it?

In seeking to answer these questions, this paper builds on a number of previous literature surveys. Much of the material in section II and III is adapted from a previous paper by Brynjolfsson [1993]. An earlier study by Crowston and Treacy [1986], identified 11 articles on the impact of IT on enterprise level performance by searching ten journals from 1975 to 1985. They conclude that attempts to measure the impact of IT were surprisingly unsuccessful, and attribute this to the lack of clearly defined variables, which in turn stems from inadequate reference disciplines and methodologies.

A review of research combining information systems and economics, by Bakos and Kemerer [1992], includes particularly relevant work in sections on macroeconomic impacts of information technology and information technology and organizational performance. Many of the papers that seek to directly assess IT productivity begin with a literature survey. The reviews by Brooke [1992]; Barua, Mukhopadhyay and Kriebel [1991]; and Berndt and Morrison [1995] were particularly useful. Most recently, the first part of Landauer’s [1995] book details research results surrounding the productivity puzzle. Wilson [1995] also provides a useful survey of twenty articles.

Although this review considers about 150 articles, it cannot claim to be comprehensive. Rather, it aims to clarify for the reader the principal issues surrounding IT and productivity, by assimilating the results of a computerized literature search of 30 of the leading journals in both information systems and economics, and by including discussions with many of the leading researchers in this area, who helped identify recent research that has not yet been published.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section summarizes the empirical research that has attempted to measure the productivity of information technology. Section III considers aspects of the productivity puzzle which remain unsolved in spite of recent studies confirming IT’s favorable impact on productivity. It classifies the explanations for the remaining paradox into four basic categories and assesses the components of each. Section IV concludes with summaries of the key issues identified and with some suggestions for further research.

II. Research on the Productivity Effects of Information Technology

Productivity is the fundamental measure of a technology’s contribution. While major success stories exist, so do equally impressive failures. (See, for example [Kemerer and Sosa, 1991; Schneider, 1987].) The lack of accurate quantitative measures for the output and value created by information technology has made the MIS manager’s job of evaluating investments particularly difficult. Academics have had similar problems assessing the contributions of this critical new technology, and sometimes this has been interpreted as a negative signal of its value.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, disappointment in information technology was chronicled in articles disclosing broad negative correlations with economy-wide productivity and information worker productivity. Several econometric estimates also indicated low IT capital productivity in a variety of manufacturing and service industries. More recently, researchers began to find positive relationships between IT investment and various measures of economic performance. The principal empirical research studies of IT and productivity are listed in table 1.