Debt reckoning Real Deals

Post on: 16 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

A group of experts discuss bank debt, adjusting for ABL and the return of the dividend recap.

26 June 2013 by James Harris. Permalink .

The interviewees:

Jon Herbert. director of LDC

Anthony Gardner. managing director of structured finance at Palamon Capital Partners

Gareth Healy. investment director at Inflexion

Martin Morrin. managing director at RBS Invoice Finance

Paul Bail. managing director of RW Baird

Paul Shea. partner at Beechbrook Capital

Michael Crosby. partner at Proskauer

A number of private debt investors have raised funds recently, but in Europe the market is still dominated by banks. To what extent is bank debt readily available and is it being priced sensibly?

Healy: Generally it’s good. It has been slowly improving, although we found in the downturn it was still relatively easy to get finance for a good-quality asset. The overall quantum has gone up and lenders have been more aggressive. However, it does depend on the sector. Some banks are not interested in consumer or automotive, so it’s important to know which banks are comfortable with which sectors.

On the whole, pricing has stabilised at 4.5 or five per cent over Libor, but the real news is there is more innovation around unitranche and mezzanine, and therefore more flexibility.

Herbert: It’s a lot better than it was 12 months ago, and an awful lot better than it was 18 months ago, when we were still in the throes of the eurozone problems. If you look at the total cost of debt, it has never been cheaper than it is today.

Banks are reasonably cautious in my view but they’re getting more aggressive. Unitranche is obviously very helpful and that has become much more competitive than it was 12 months ago, when there were only one or two players. Now there is a handful, so there’s more competition.

Gardner: It’s difficult to generalise. For the bigger assets, and we have a few in our portfolio, we see very competitive pricing. There is a dramatic improvement in quantum and terms, but for assets with less than £10m (€11.7m) Ebitda, it’s challenging to get a competitive process in place. There are still not that many providers even though credit funds have been popping up with some regularity.

As a private debt investor that has recently reached a first close on your latest fund, would you agree with that Paul?

Shea: We’re different because we focus on companies with Ebitda of less than €10m. For deals over that size, we’d need a co-investor – it’s much more competitive and it’s difficult to generate the returns we’re looking for in those larger deals.

Crosby: We’ve set up a number of funds for US and European clients, who have successfully raised a fair amount of capital. Certainly the lower mid-market space allows for good pricing and real value-add from the bankers’ perspective. It’s a specialist niche market and not everyone can play in it, and that is where investors are more likely to see the most interesting returns.

A lot of capital for private debt funds has been raised; do you think some of these new entrants will struggle to meet their return expectations, especially at the more competitive larger end of the market?

Crosby: It depends on the structures and terms that debt funds manage to secure. If they are sensible long-term mezz investors who want to stay in this market for the foreseeable future and have a track record, they are going to accept lower pricing and lock in returns on a two-year basis, and boost returns by investing across the capital structure.

Some funds have greater flexibility to do that. I’ve represented a number of mezz funds that have done pure equity investments in the last 12 months. That trend is likely to continue.

We’re seeing a greater flexibility in funds documentation. It is becoming more common

to see the type of structures that you’d see at the likes of Apollo and KKR – global pools of capital that can be deployed in different sectors and across the capital structure to generate the best returns. We’ve already seen it in the US – it makes sense that it will be more common in Europe in the future.

Shea: Funds aren’t just competing on price, that’s one thing. It’s also a question of offering different products and having a swift investment committee process. Mezzanine and unitranche may seem more expensive but if you consider that these loans offer no amortisation and more flexible covenants, it’s a good product so naturally there’s a higher price.

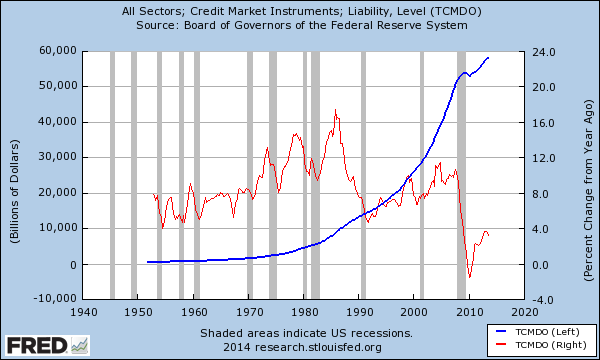

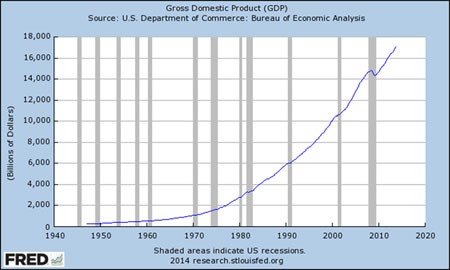

But as we have to raise funds in private markets, we don’t benefit from people printing money and giving it to us cheaply. Capital is a scarce resource. So what is the real cost of money? If the all-in cost of senior debt is four or five per cent, and real inflation is 2.5 or three per cent, people are making a return of 1.5 per cent or two per cent. Is that the return that investors should be getting for financing a leveraged buyout?

In our experience, the market cost of money is higher. What we offer is much more in line with where the risk return should be. As I said, the price of senior debt is artificially deflated. That’s having a number of knock-on effects like keeping companies alive with inefficient balance sheets, and it is stalling the future growth of SMEs.

A lot of big funds are coming in and looking to invest large amounts, such as £50m in one bite size. The question is how are they going to deploy that? It seems likely that returns on larger unitranches will be driven down to seven or eight per cent as these lenders compete with banks and each other.

Gardner: That raises an important point. The senior banks are not making money on the margins. They are making money on arrangement fees of four per cent, as well as the ancillary services such as hedging, forex and so on.

Healy: Banks need companies to do refinancings so they can charge high fees. In most LBOs, the minute anything changes, banks charge whacking great fees.

Are we moving towards the US market, where over 80 per cent of capital is institutional, or will some of these funds withdraw from the market?

Shea: We don’t cover the US market in too much detail but we understand that there’s a huge amount of liquidity there. As opportunities became scarcer, investors start to look to other markets. In Europe, they see there is a shortage of debt finance. The problem is they have to invest large amounts to shift the needle. Someone wants to deploy a billion dollars direct lending in Europe; I don’t know how they will do it, because you’ll need a lot of resources – people to originate and execute deals, and then manage the portfolio. It’s very costly to set up. It’s not an unlikely scenario that some of the funds that can’t deploy capital will close down. That said, I do think the number of institutional providers of debt finance in the European market will increase.

Herbert: It’s clear that the more sophisticated funds that have been around for a while are starting to partner with banks for precisely that reason. There is a significant challenge deploying capital in a market where the total volume of M&A is still weak. It makes sense to team up with banks, which clearly have greater distribution. I think we’ll see new structures as a result.

Bail: Private debt funds are finding it hard to deploy capital to the extent they want to. One of the ways is to partner with banks, which can take the senior debt and the risk that they’re comfortable with, while debt funds can get a decent return at a sensible price. From a bank’s perspective, if you believe capital is going to become scarcer and more expensive, and debt funds will encroach, why wouldn’t you team up with debt funds and make sure you protect your market share, get revolving facilities and perhaps some ancillary business, and hold on to your relationships?

We’ve talked about mezzanine and unitranche. Is appetite for ABL still strong?

Morrin: In terms of acquisitions, we’ve had a very strong 12 months. I think the ABL market is in a relatively healthy state. We’ve invested a lot in ABL at RBS in terms of building a solid team. That’s been a task we’ve been undertaking for the last three years and it’s paying dividends.

Have you had to adjust your offering to take into account some of the new market entrants?

Morrin: Slightly. It depends on the circumstances and that tends to be led by the sponsor. If it makes sense for all of the parties, we will adjust our position to participate. If it doesn’t, we won’t.

Shea: We’ve seen the asset-backed lenders come quite aggressively into the lower mid-market, taking the position that the banks have vacated. We completed one deal recently in which an asset-backed lender provided a facility and we did a mezzanine tranche behind that. We have some concerns about the commitment of ABL providers because in the standard documentation, they have the right to change the advance rate at any moment. Of course, they say they’d never do that, but they’re allowed to. It took us a while to get comfortable with what was being offered and get the right protections in place.

Herbert: We found we often came to a barrier because of the commitment point that Paul made, so we tend to only use ABL for re-financing purposes. For new investments, we’re not a distressed investor, and we find it very difficult to structure a deal with ABL for precisely the reason you make. Did you find a way around that?

Shea: It depends on the quality of the assets that are being used as collateral. If it’s an illiquid property in a remote location then replacement finance may be difficult to find. If it’s invoice discounting for a range of five supermarkets, then it’s a different refinancing risk. You can also mitigate the risk with support from sponsors, or maybe have another debt provider lined up. We are keen to support new lenders into the market and so are happy to find a way to get comfortable with their requirements.

Morrin: We’ve adjusted our position and I suspect the market has as well with regard to those commitments. You have to look at the security and the returns. We’re not generally pricing unsecured risk in those situations, we’re pricing secured risk. But I do think there has to be a balance between your commitment and your security. As the market evolves, what I’ve seen over the last few years is a focus on the security of the assets, but also the performance of the business. While we don’t want to be in a market where we’re covenant-heavy because it doesn’t play out well, you can structure so it’s covenant-light, where at least you can have specific points, so you can look at where you are in the cycle and the performance of that business, and decide whether it needs to be adjusted. In those situations, it’s in everybody’s interest to work together to do that.

Paul, what does the syndication market look like today?

Bail: The syndication market has been strong. What we’re seeing is a number of deals being done, but they are more focused on refinancing and leveraged recaps at the higher end of the market. There isn’t enough flow in new deals. You can tell there is huge demand because we’re seeing deals being repriced three to six months after being launched. That tells you there’s a lot of money that is looking to be invested. Investors are still hungry for yield, and they’re willing to take a bit of a cut in pricing.

Commentators are saying that the CLOs and CDOs are reaching the end of their investment periods so they want to get as much money out the door as they can. Clearly investment bankers and private equity players are seeing that as a great opportunity, and they’re making the most of that. The big issue is when those reinvestment periods do run out there will be a lack of liquidity in the market and that is going to be a big test for underwriting. There is a new fund that is being raised specifically to look at that maturity of debt and refinancing those deals, which is an interesting concept.

There is definitely an opportunity in the future. When the CLOs and CDOs are no longer there, there’ll be an opportunity to invest at a higher margin. Those are the basic dynamics in the syndication market. A major change in the last few years is the growth in the high-yield market, which has been responsible for around 50 per cent of refinancing deals, and that clears up capacity for the banks to invest elsewhere. Even as we speak, the high-yield market continues to fly. That said, that market can easily open and close. At the moment, it’s continuing to absolutely fly, and that’s helping. If you look at the maturity wall, it has been moving backwards and has been doing so consistently.

Herbert: How do you feel about loan underwriting in the mid-market, and I mean the proper mid-market?

Bail: That’s very difficult. If you’re a bank and you have £100m to underwrite, who are you going to sell it to? Other banks are going to demand the market fee. It’s difficult for one bank to stick its neck out, so club deals will continue to a large extent. Having said that, when you talk to some of the UK clearers they have quite demanding budgets, and they’re looking to see how they can put money to work. They’re more willing to look at underwrites in the mid-market than they were. In the future, the debt funds will see that as a great opportunity. Instead of four banks, sponsors may deal with just one debt fund.

What are you seeing in the syndication market from an ABL perspective, Martin?

Morrin: In our team, we focus more on getting the structure right and if it requires either a partner from a club perspective or a syndication, one of the benefits of using ABL is that it’s not as capital-intensive in terms of hitting hurdles, so it’s easier to achieve. Our experience of the syndications market is that it’s relatively healthy. We don’t struggle to find partners to execute deals. The more you do with partners, the better the understanding of other investors’ appetites. That’s fundamentally important. Last month, we closed a syndication for $1bn (€747m) in the UK alongside other banks. These things are being done. From my perspective, pricing isn’t the issue. The structure and risk appetite is the challenge.

Paul mentioned the impact of the high-yield bond market – do you think it’s here to stay?

Gardner: We’re not big users of high-yield bonds but we’ve just done one. The market is on fire, and pricing is very competitive. We completed a £300m deal that gives us a lot of flexibility. It’s the right product for that asset. We very nearly managed to get a high-yield bond issuance for another asset. We had done the prospectus, the roadshow, but the market opens and shuts very quickly, and that’s exactly what happened. Just as we were about to go to market, it shut.

Crosby: There aren’t many people who would look at the high-yield bond market and say it is sustainable. Everything that’s happening suggests there will be a reversion to the mean. At the moment it’s a bell curve where pricing is far out to the left, with a small shift back to what would be considered a more normal level.

There’s a long way to go and it seems likely that a lot of pension funds and other investors that are holding on to that kind of paper are going to experience quite a lot of pain in the future. An increase in high-yield pricing is going to have a depressive effect on the overall price of fixed income investments. The clear message is that high-yield pricing is unsustainable and we’re going to see a significant change. Some people are saying that it won’t change because of the low interest rate environment, but if you look at long-term pricing, something very strange is happening.

Do you think that the retail bond market will play a meaningful role for lower mid-market businesses?

Healy: There’s not enough evidence to know what’s really happening there. Possibly the closest thing to a mid-market buyout is the Alpha Plus schools deal, which was a £50m issuance. It looks like it priced at a massive multiple of Ebitda but it was backed up by a lot of property. Most retail bond issuers tend to have a story – either a consumer brand that people flock to or a big asset base.

Herbert: It’s not practical for M&A. You can’t go into a process with a retail bond to finance the deal, So you can only do it on a refinancing basis because the way of arranging it doesn’t fit with an M&A process.

Is the level of defaults likely to increase?

Bail: Defaults increased during the recession, but they’re generally quite stable now. If Europe goes into a big downturn, or there’s some kind of geopolitical event, that might change.

Healy: The real risk to a high-yield investor is not defaults but sentiment. The window opens and closes. Liquidity is very patchy, especially for retail bonds. If confidence changes it will be very hard to sell bonds, and prices will drop.

Shea: Cause and effect has changed. Rather than defaults going up, which in turn impacts activity, the market is so buoyant that defaults are artificially low because issuers are easily refinancing companies that ought to be restructured. Problems are being pushed down the road. When the liquidity goes because, say, the Fed stops printing money quicker than expected, or something we don’t know about happens in China, the market could stop. Something unrelated to the general credit quality of European companies will affect liquidity and once you can’t issue a high-yield bond quickly and refinance amortising bank loans, there will be a spike in defaults.

Dividend recaps have come back very strongly this year. Are they being widely used by mid-market companies?

Gardner: They are a very useful alternative to selling an asset. We all know it’s a difficult and lengthy process to sell assets at the moment. We’ve done a number in the last few years, including one where we took more than our investment capital out. It all rather depends on the asset and the extent to which the sponsor is taking money out.

It has become easier to have those discussions with banks, that’s for sure. Just 18 months ago it was out of the question, and even if it were possible, there was no way you’d be able to take more than the investment capital, so 1x was the absolute limit. It’s looking a little different now.

Herbert: LDC is pretty cautious about dividend recaps. We did a couple last year, and we’ve done one this year. They are very useful, but personally what I don’t understand is why it’s so difficult to sell assets when we’re all so keen to buy them. I keep scratching my head about that. Even though they have come back, it’s rare to take out more than the invested capital.

Healy: That always seemed irrational to me.

Herbert: As a former banker I don’t think that at all. If you look at the performance of recap portfolios for banks in the last cycle, they were materially worse than primary deals. You can argue that half a turn less leverage is too aggressive for banks. It should be at least a turn lower in my opinion.

Bail: There is a marked difference in how banks look at dividend recaps and how debt funds look at them. Banks looked at portfolios and saw the performance of dividend recaps. They won’t move away from those parameters easily. Debt funds can come and take a different view, and look at it as a new credit. They probably won’t leverage it up to the initial level of the deal but they can stretch it. They are more likely to look at skin in the game and take a more aggressive view of what money can be allowed back to the sponsor.

Shea: In the lower mid-market, it’s still pretty rare. We’ve had a couple of enquiries but have declined them so far. We have finite capital and plenty of primary opportunities to look at, which is what we prefer. If the right deal were to come along we would consider it, but at the moment new buyouts are more attractive to us.

Finally, we’ve talked a lot about the UK, but I’d like to talk about other European countries. Palamon invests across Europe – how much easier or harder is it to access debt in other markets, Anthony?

Gardner: In some markets, it’s extremely difficult to find acquisition finance. Here’s one recent example – we were looking to do a deal in Italy and we needed ¤12m, which is not a big number. We had to bring together four banks. Why? Partly because there are few dedicated acquisition finance providers in those markets. We had to turn to regional and local banks, some of whom would not normally work on these types of deals. We found ourselves contemplating a club deal of four banks for a small acquisition. It’s very tough to do that in a jurisdiction like Italy. Some of the bigger banks are still active but only for the jumbo deals, of which there are only maybe two per year. Smaller deals are out of the market. There are also very few deals in Spain. Doing deals outside the UK, it’s very important to have good relationships with local banks.

Bail: I’d agree. We’re working on something in Italy. We got some offers from banks but it’s extremely difficult to get banks in Italy together to form a club. In Germany, by contrast, I’d argue there is more debt available than in the UK. A lot of German banks are active in the mid-market leveraged finance space. The Nordic market has also been strong. Meanwhile, in France, unitranche has done very well.

Shea: We invest across Northern Europe and in Germany there seems to be a decent amount of bank provision. A lot of those banks had troubled balance sheets even pre-crisis, but they’re still lending freely.

Crosby: We’re still seeing a good deal of interest in Scandinavia and what we call the beer-drinking countries – the Benelux and Germany. We are seeing a renewed interest in places like Italy, Spain and even Greece, although the underlying difficulties of doing deals in those countries is still there. Investors are definitely looking at more exotic jurisdictions, especially Turkey. We’ve seen a number of enquiries from clients about credit rights and the extent to which investors can enforce their security in the country. Notwithstanding the current political difficulties, we see a longer-term trend of increased dealmaking in Turkey if current conditions continue in Europe.

Real Deals would like to thank RBS Invoice Finance, RW Baird, Proskauer and Beechbrook Capital for making this roundtable possible.