Why A Mortgage Is Not Actually An Inflation Hedge Itself But Can Provide Access To Investments

Post on: 26 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Why A Mortgage Is Not An Inflation Hedge

While a mortgage is often viewed as an inflation hedge, due to its fixed (at least with a conventional mortgage) payments that don’t change even if inflation arises, the reality is that a mortgage alone isn’t really a hedge that benefits from inflation. It’s not necessarily a harm, but it’s not a benefit, either.

To understand why, imagine for a moment that someone has a $500,000 house, and decides to take out a $400,000 30-year (fixed) mortgage at 4%. To avoid getting into a future cash crunch, the individual then takes the $400,000 in proceeds, and uses them to buy a series of laddered bonds that have a comparable yield to secure each mortgage payment as needed. This “perfect” asset-liability matching effectively immunizes against any risk that a change in interest rates could adversely impact the situation (assuming there are no bond defaults).

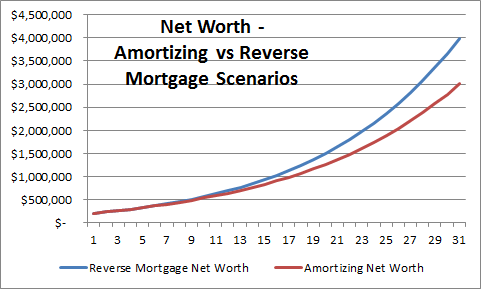

Now imagine that after engaging in this strategy, inflation really does spike higher. Suddenly, inflation is running at 7%. Intermediate-term interest rates jump close to 10%. Within the span of a decade, the value of the house itself has doubled to $1,000,000 (just keeping pace with inflation). Given this “surprise” inflation event, the chart below shows the individual’s current financial situation, comparing the scenario with a mortgage (which would have amortized down to a remaining balance of about $315k) versus the alternative scenario without ever bothering to get the mortgage.

As the results reveal, the presence of the mortgage itself, with the mortgage payments managed by a bond portfolio at similar interest rate to cover the requisite payments, is not worth anything more than the scenario that eschews the mortgage and just keeps the property itself. Either way, the net worth is exactly the same. It doesn’t matter whether inflation and interest rates rise or fall, the outcomes are always identical (at least on a pre-tax basis, but generally on an after-tax basis as well, assuming bond interest is taxable and mortgage interest is deductible).

It’s Not How Much You Borrow, But What You Buy “On Mortgage” That Counts

Of course, the caveat to the scenario above is that the proceeds of the mortgage were used to acquire a portfolio of bonds that would immunize the mortgage payment obligation. If the funds were used for a different kind of investment, the outcome can be quite different.

For instance, imagine instead that the proceeds were used to invest in a portfolio of TIPS bonds, with what (at the time of this writing) would be a real yield close to 0%. If inflation is only 2%, the bond portfolio is actually undermined by the mortgage overtime, as the debt effectively “compounds” at 4% while the bonds only yield 2% (or in practice, the individual would have to liquidate an increasing quantity of TIPS bonds to cover the mortgage payments since the interest alone is insufficient). On the other hand, if inflation again spikes to 7% instead, suddenly the TIPS bonds are providing more than enough nominal yield to cover the mortgage payments (or technically, TIPS principal would be increasing by enough that fewer and fewer TIPS bonds must be sold). Either way, the real estate itself is assumed to grow at the rate of inflation. The end result after a 10-year period of time – now there is a significant difference between the high- and low-inflation scenarios.

As these scenarios reveal, while the presence of the mortgage itself doesn’t matter (as noted earlier), how the proceeds are allocated does. In reality, the outcomes are not actually dictated by the presence of the mortgage itself, but the decision to use (fixed rate) financing to purchase an investment that itself generates a lower or higher (nominal) rate of return. In other words, the outcomes are not actually driven by the mortgage itself as an inflation hedge, but using the mortgage proceeds to buy an inflation hedge “on mortgage” .

Likewise, if the portfolio was used to buy equities (which also function at least indirectly as an inflation hedge as rising inflation ultimately lifts nominal earnings and stock prices), the high-inflation scenarios may perform better than the low-inflation scenarios, but not because the mortgage itself was an inflation hedge, but because a loan was used to purchase an actual inflation hedge (hopefully with enough expected return to justify the mortgage-leverage risk !).

Similarly, if the mortgage is acquired with the hopes of leaving funds liquid to be reinvested in bonds in the future at higher rates (if rates rise enough, future bonds could actually pay more than a current mortgage rate at a similar level of risk), the scenario is still one that will succeed – or not – by the returns that can ultimately be obtained by the portfolio. In essence, this means that the use of the mortgage becomes a form of call option that will be “in the money” if rates rise enough to exceed the borrowing rate. The outcome may be better in high-inflation scenarios, but only because it causes the option “investment” to pay off, not as a function of the mortgage itself. On the other hand, if inflation (and rates) do not rise, this “interest rate call option” approach can become highly unfavorable as well; in fact, as with most forms of leverage, just as a mortgage can magnify the positive outcomes of inflation hedges, so too can it magnify the negative outcomes if inflation does not come!

A Personal Residence As A Hedge Against (Rent) Inflation

In some situations, the reality is that there is no portfolio to match to the mortgage at all; the loan was necessary just to purchase the real estate in the first place.

Notably, though, even these situations, where a personal residence is often viewed as a “dormant” asset (since it doesn’t provide an ongoing cash flow or income yield), the residence is actually still functioning as an inflation hedge. Not merely because the price of the real estate itself will tend to move in line with inflation, but because owning a personal residence actually does have an implied cash flow yield – in the form of the rental payments that are not being paid from cash flow.

Thus, for instance, if rents rise unexpectedly (or begin to inflate rapidly), owning real estate insulates the owner from any direct exposure to a higher rent obligation – which is especially valuable in situations where rental increases outpace wage growth. Or viewed another way, the residence pays a “yield” in the form of covering the equivalent of rental living expenses, and that yield is automatically implicitly indexed to inflation; if/when/as inflation lifts up, the amount of rent replaced by ownership of the residence automatically has risen as well.

Even in these scenarios, though, the reality is that the “benefit” of owning a residence to hedge against the impact of inflation on rents is actually a function of owning the residence. not a function of having a mortgage. As shown earlier, for those who can afford the choice of having a mortgage or not, there is no benefit to the mortgage itself (except to the extent its proceeds are invested favorable). On the other hand, in this context a mortgage can be valuable as a path to an inflation hedge; in other words, once again the mortgage itself wasn’t an inflation hedge, but it was used to buy one!

Wages As An Inflation Hedge

It’s also notable that in situations where there is no separate portfolio or (material) assets and the mortgage is necessary to purchase a residence in the first place, the reality is that the mortgage will only eventually be paid off by (future) wages. And to the extent that inflation rears up, the mortgage will become increasingly easier to pay.

Even in this scenario, though, the key factor is still not that the mortgage is an “inflation” hedge, but that wages and the ability to work is. If inflation does rise up, the mortgage may get “cheaper” relative to income and easier to pay, but not literally because the mortgage depreciated in value; instead, the real driver is that wages will (tend to) rise in line with inflation, and it’s the wages-as-inflation-hedge that improve the outcome. After all, if someone is unemployed and has no other source of income, it’s pretty easy to see that inflation or not, it’s difficult to pay the (nominal) mortgage payments at all; inflation doesn’t make the mortgage any cheaper in future dollars if there are no inflation-adjusting future dollars coming in to pay with in the first place! And if there are, the benefit is the inflation-adjusting income source, not the mortgage itself!

The bottom line, though, is this: despite often being celebrated as an inflation hedge, having a mortgage itself does not actually function as such. A mortgage may free up assets to invest into an inflation hedge, or used to purchase a residence that functions as an inflation hedge, or be paid for with wages that are themselves inflation-hedged. But in the end, those outcomes are dictated by the inflation-hedging benefits of how the mortgage or its proceeds are used, or how it will be paid for… not by the mortgage itself! And as with any leverage, the outcomes can cut both ways, with mortgage leverage magnifying both the positive and negative scenarios!

So what do you think? Do you consider a mortgage to be an inflation hedge, or is it actually about how the mortgage funds are used? Have you ever recommended the use of a mortgage as an inflation hedge? Should more focus be given to how mortgages are used to gain access to inflation hedges?