What happens if Greece leaves the euro

Post on: 9 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Live feed Show

Order by

- Newest first Oldest first

9.01am: The Greek prime minister George Papandreou’s pledge to put the bailout package for his country’s beleaguered economy to a referendum has thrown the eurozone into crisis and will dominate today’s G20 meeting in Cannes. Overnight, the question of the bailout deal has morphed into a more fundamental question about Greece’s membership of the eurozone.

Photograph: Maurizio Gambarini/EPA

Angela Merkel (left), the German chancellor, and Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, have issued an ultimatum to Greece to agree the deal or leave, making it clear that they would favour insulating other vulnerable and larger economies such as Italy over throwing everything at saving Greece. Merkel said last night.

We would rather achieve a stabilisation of the euro with Greece than without Greece. but this goal of stabilising the euro is more important.

Meanwhile, Papandreou has suggested that the referendum question would be about membership of the euro rather than the terms of the bailout, a vote that he is far more likely to be able to win. Polls in Greece have shown that 60% of the population are against the terms of the bailout — which includes new austerity measures — but 70% are against leaving monetary union. The referendum has triggered a dramatic split in his government that is increasing the threat to his position by the hour.

Professor Ken Rogoff, the Harvard economist and former chief economist at the IMF, told BBC Radio 4 today that the Greeks are going to end up defaulting hugely no matter what, adding:

The odds that they will be gone from the euro within a few years are very high.

No country has every left the euro before and there are no provisions about how they might go about it.

What happens if Greece is either forced or chooses to leave?

Throughout today, I’m going to gather expert opinion to build up an image of the scenarios under which they might happen and assess the potential fall-out for Europe and the global economy. Can you help?

Leave your comments below the line, email me at polly.curtis@guardian.co.uk or tweet @pollycurtis .

My colleague Graeme Wearden is live-blogging all the breaking news about the eurozone crisis here .

Andrew Sparrow is live-blogging from the G20 meeting in Cannes here .

10.04am: I’ve been speaking with Alan Clarke, an economist at Scotia Capital. I asked him what the impact of Greece leaving the euro would be. He said:

It’s uncharted territory. Either way you look at it, it’s bad. It’s not a soft-option for Greece. They are spending about 8% on GDP more than they are receiving in taxes. If the population aren’t happy with another 100,000 lay-offs and reject the deal, the government won’t be able to borrow and pay anyone.

For the eurozone it’s bad. A lot of the EU banks are exposed to Greece, the initial ESFS deal said they would lose 21% of value of holdings, now it’s more like 50%. if it’s the whole hog of 100% that would have serious implications for EU banks. It would look like [the bankruptcy of] Lehman Brothers if banks go bust particularly if you have contagion. You have serious risk of bank failures. Take cover. There would be 110% chance of recession if Greece goes bad.

Unlike Lehman’s we’ve had a lot of warnings of this. It’s been going on more than a year. Mervyn King has stated that contingency plans have been prepared. It would take the sting out, some of the shock factor. But we saw how the stock markets deteriorated at talk of the referendum. We’ve seen sharp falls in business confidence throughout Europe. Greece is small but it’s the trouble maker of the eurozone. The damage it’s doing to more significant countries such as Italy is immeasurable. My glass is half empty on this.

PMB Paribas is exposed to Greek debt by around €5bn. France and Germany are in the most vulnerable positions. RBS was exposed but I think Mervyn King told the UK select committee that contingency plans were in place. Although UK banks are not huge directly exposed, indirectly they will be affected and that’s hard to unravel and assess the risk we face.

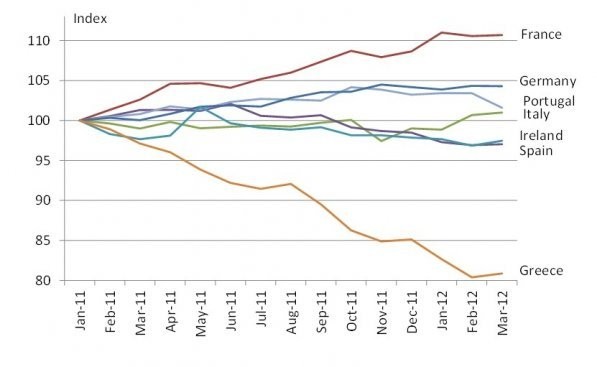

My colleagues on the Guardian’s datablog compiled this back in June documenting the banks that are exposed to Greek debt. It shows that after Greece, France, Germany and Belgium’s banks are most vulnerable. The table below shows the banks most exposed as of June this year.

Photograph: David Jones/PA

I’ve just looked up the evidence that Mervyn King (left) gave to the Treasury select committee that Alan Clarke mentions; you can read it here. He makes clear that there have been contingency plans put in place by the UK government but doesn’t go into the specifics. He says:

If you look at the provisions for liquidity insurance that we have put in place for our own banking system, they are radically different from the ones that were in existence in the summer of 2007, when the financial crisis began. We learnt from that experience, and we have put in place now special auctions for liquidity, which we can introduce immediately if we need to.

Larry Elliott, the Guardian’s economics editor has just filed this in which he explains the European politics behind the possibility of a Greek exit from the euro — and raises the possibility of the break-up of the eurozone.

10.46am: The National Institute for Social and Economic Research has published a paper today looking at the various scenarios for Greece, one of which is its leaving the eurozone. Dawn Holland and Simon Kirby write:

In such circumstances, devaluation is certain, and explicit default is also likely. This would lead to lower interest payments on government debt, and lower asset prices could also result in capital inflows. Under such a benign scenario, output would rise, perhaps quite sharply, much as it did in similar circumstances in Argentina in 2001-02. On the other hand, there are very large downside risks (in particular, the difficulties of full currency redenomination, and the possibility of forced EU exit) that were not present for Argentina.

I asked Dawn Holland to expand on this a bit for me, and she gave me a slightly more optimistic view, but not much.

Argentina was a dollar based country and they reintroduced the peso in 2002. They converted all bank deposits into the new currency overnight. There was a massive disruption, capital flew out of the country. But over time capital began to flow back in. They had a relatively successful outcome. The Argentinian case is the best possible outcome with capital flowing back in.

You would expect this new currency is going to devalue massively. In Argentina it devalued by 200%. If this happened in Greece it would devalue by at a very minimum 50%, we think. For people outside of Greece paying in euros or other currency suddenly Greek assets look relatively inexpensive and people could start to invest. There is risk attached to that, but if devaluation is big enough, you can expect investors to see this as a profitable place and put their money in. That’s the best outcome.

The worst case is that the risks are too great, nobody puts money in, and Greece is completely cash strapped. They won’t be able to pay back their debts. If we don’t get foreigners stepping in to buy up the domestic businesses, then Greece’s economic outlook is much worse off.

But the point of getting your own currency is that you can just print the money to pay off your debts. If they had their own currency and central banks they could just print the money for their debts. In the short term you can do that. That leads to high inflation and it’s not really viable for any longer period of time.

I think things would be a lot worse off to leave to monetary union. But if you look at the Argentinian experience there is a potential outcome which would put Greece in a better position. I wouldn’t write that off. There’s no guarantees that we will end up in that position and risks are so high. It’s a very high risk strategy.

The risks are: inflation, devaluation, banking collapse. But that’s possibly going to happen now anyways. Once the policy is on the table as something to debate, it is very likely we will see a run on the Greek banking system. Anyone with savings in euros in a bank is going to take them out. The banking system could freeze up way before we get to a referendum in December. The euros that are already out there in cash will remain in euros if Greece leaves the EMU. People will hold on to their euros as long as possible fearing devaluation of a new currency. No one will spend money they don’t have to spend. That will mean a complete collapse of the economy is very very likely — even at the suggestion of exiting the euro.

12.16pm: In September, economists at UBS published research on the possible consequences of a euro break-up. You can read the whole thing here (pdf). It looks at a hypothetical exit of a country, or break-up of the eurozone, rather than the specifics of what were to happen if Greece leaves. But it’s a very useful insight. The main points (paraphrased from the report) are:

• There are no provisions to expel a country without amending the Maastricht treaty and to secede is incredibly complex. Negotiating an exit would require re-writing an EU-wide agreement and re-writing the treaties of the EU, which in turn requires referenda in several member states. Any single government could veto the move. The paper concludes that leaving legally does not seem to be a viable option. An exiting country would have to leave the EU and though it could later apply to re-enter, the other member states who would be seriously disadvantaged might not let them.

• If a weak country (such as Greece) were to leave they risk: sovereign default, corporate default, collapse of the banking system and collapse of international trade. They conclude (unlike the NIESR economists above) that there is little prospect of devaluation offering much assistance by way of inward investment — partly because disgruntled neighbours might not inclined to invest. They estimate that a weak euro country leaving the euro would incur a cost of around €9,500 to €11,500 per person during the first year and €3,000 to €4,000 per person per year over subsequent years. That equates to a range of 40% to 50% of GDP in the first year. A strong country would risk 20-25% of their GDP in the first year by leaving.

• A country that leaves the eurozone is likely to default on its debts (with consequences for the wider banking system) and its domestic banking system is at risk of collapse as people withdraw their money to avoid a devaluing new currency.

• Monetary union break-ups rarely occur without mass civil disobedience and even civil wars, the paper warns.

By the way, we temporarily lost our comments due to a technical hitch. Apologies for that. Any more problems do email me at polly.curtis@guardian.co.uk .

1.04pm: In the comments @Ldexter questions the impartiality of the UBS report. Both UBS and Scotia Capital, who give the more pessimistic views, of course have vested interests here. I was pointed towards the UBS research by economists at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and felt it was valid to mention particularly as it has the best analysis I’ve been able to find on the legalities of leaving the eurozone.

Also in the comments, @congregational points us towards this paper (pdf) conducted by the Monetary Authority of Singapore in 2007 assessing all monetary union exits since the second world war. It concludes that actually many of those 60-odd economies studied recovered relatively quickly, although it also says the trend was for more stable economies to leave monetary systems. Greece can’t really be described as stable. The report, written by Professor Andrew K Rose of Berkeley University, California, concludes:

I find that countries leaving currency unions tend to be larger, richer, and more democratic; they also tend to experience somewhat higher inflation. Most strikingly, there is remarkably little macroeconomic volatility around the time of currency union dissolutions, and only a poor linkage between monetary and political independence. Indeed, aggregate macroeconomic features of the economy do a poor job in predicting currency union exits.

2.12pm: Some more views on what might happen if Greece leaves the eurozone:

Dr Spyros Economides a political scientist at the London School of Economics with a research focus on Greece and the EU, said he thinks that Greece leaving would be a disaster and dismisses the arguments put forward by some on this blog that a cheap drachma would give Greece an economic advantage in the global economy. He said:

We’ve seen no credible alternative of what happens if it returns to the drachma. Some economists ague that having the drachma back would allow Greece to be more competitive on the international stage. In economic theoretical terms that’s all well and good, but I don’t know what they produce to allow that? People say the tourism. but there are limits to how much the tourism industry can expand and absorb. What can we say that Greece produces or exports that allows it to be more competitive?

You can talk in economic terms but fundamentally this is a political problem for Greece. Bad-faith, ill-will, untrustworthiness, these have all cropped up for Greece since the eurozone crisis started. What credibility does Greece have in terms of attracting investment? It will be very, very difficult. Cheap currency will attract some commercial concerns, but it’s no guarantee that anyone will take it seriously.

In fact [if Greece leaves] all those funds that are being pumped in to rescue Greece could be put into investigating in a firewall around Italy. That could save the eurozone. Saving the eurozone is about political will. It’s convincing the electorate and taxpayer in every member state that we have to do this because it’s in the future interest of us and our successor.

His colleague, Dr Vassilies Momastiriotis. a senior lecturer in the political economy of south eastern Europe, told me that he does not believe that Greece will leave the eurozone, saying he expects a political resolution to the problem, but if it did:

The eurozone would survive but there would be a big shock for the banks. There are preparations to shore up the banks and the costs of the defaults. But the further consequences would be in economical and political sense disastrous. I think it would be hugely politically disabling, and that’s more important than the economic sense. Greece would end up with a more nationalist agenda as inflation speeds up and poverty rises. There is going to be much more support away from the centre of the political spectrum.

The government will have to step in and nationalise the banks, the banks are of course going to default on their current debts. There would be a total collapse of the economy. Devaluation, very high inflation, an increase in unemployment. Greece would go bankrupt. The country will be able to print more money to pay its bills but that money won’t be worth anything.

The aftershock for the eurozone will be lower than previously expected for other countries. If the eurozone was the thing that caused Greece to exit then it would mean that the eurozone had failed to support ailing countries. If Greece walks out on eurozone, it was the inability of Greece to follow through. It will be Greece’s failure rather than eurozone’s failure. If the eurozone had failed people would be asking could it guarantee keeping Italy or Portugal in?

2.34pm: The Guardian’s correspondent in Spain, Giles Tremlett. has just alerted me to this (pdf) very relevant paper by the Economist Intelligence Unit. an FAQ on what would happen in the case of the break-up of the eurozone. It makes the following points, relevant to our question:

• There is no formal way for a country to leave the euro, meaning it would have to default on its terms of membership or other countries could effectively expel it by withholding support. Either way is messy.

• It says there is a major risk of contagion. If there is one departure from the euro other weak countries will follow, triggering the breakdown of the eurozone.

• It describes the consequences for those leaving the euro as numerous and unpleasant. A bank run would be likely, prolonged bank holidays would be required to prevent the banking system collapsing and after assets held in banks are converted to the new currency their value would dramatically depreciate.

• For countries that remain in the euro, it says: The most immediate and dramatic impact of a fracturing of the eurozone would be massive losses on domestic bank lending to governments and companies in the countries that had left. This would require major public intervention, possibly on an even larger scale than in 2008. In turn, this would add considerably to sovereign debt levels in Germany, France and elsewhere. Exports throughout the eurozone would decrease.

• If the eurozone broke up there would be a deep recession throughout Europe. The EIU report also suggests that this recession could stretch to the US and even China.

3.12pm:

Verdict

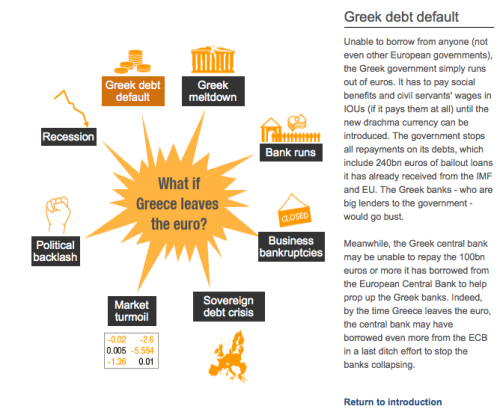

There is no formal way for any country to leave the euro without amending the Maastricht treaty requiring national referendums in several member states. Greece could default and leave, or other members could withhold funds to force it out. Neither method is strictly legal and both are very messy.

Once out, Greece would convert its euros to a new currency. which would immediately and rapidly devalue as the central bank printed money to service its loans and pay its workers’ wages and other bills. Preceding that there would almost certainly be a run on the Greek banks as people attempted to take their money out in euros to prevent them losing out through inevitable devaluation. One estimate by economists at UBS suggests a country such as Greece could lose 50% of its GDP in the first year of leaving the euro.

Economists argue that there is a scenario where a cheap new currency would give Greece an economic edge on its competitors. However, others point out that it could also be treated as a pariah state by its neighbours who might reject a fast buck on principle. Others argue that Greece has nothing to export, and its capacity for tourism is limited.

Across Europe, banks exposed to Greek debt face the risk of its defaulting on its payments to them. France and Germany are particularly exposed and could be forced to bail out their banks more than in 2008.

In the worst-case scenario, there is a threat of contagion prompting other weak countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland) to leave the eurozone, meaning the euro would collapse. Exports across the eurozone would decrease and there would be a recession that could spread across the world to the US and China. However, there is also an argument that if Greece leaves unilaterally, rather than being forced out, it will be seen as the failure instead of the eurozone, which would also have more money to put into protecting Italy, the bigger economy and therefore risk.

For the UK, economists estimate that the 50-50 chances we now face of a double dip recession would increase to 70% if the euro crisis isn’t resolved. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research suggests growth won’t return to its pre-recession peak before 2014, the slowest recovery since end of the first world war.