Value Investing Using The Enterprise Multiple

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Sooner or later, all investors face the question of how to value a business. Not how much a stock has been going up or how sales of a new product are progressing, but rather, What is this business worth given all the available facts? The textbook answer to how to value a business invariably boils down to the sum of discounted cash flows. If we estimate all the cash a business will throw off in the future and discount those flows back to the present at an appropriate rate, we arrive at the estimated value of a business.

Unfortunately, the practical answer to how to value a business tends to be quite different from the textbook version, primarily because the latter makes assumptions that are unrealistic outside the walls of the ivory tower. A discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation assumes, for example, that we (1) accurately estimate the cash flows of a business into perpetuity, (2) decide on an appropriate discount rate that accounts for both the time value of money and the risks inherent in a business, and (3) make the correct judgment about the impact of managements capital allocation choices. The latter may not seem like a component of a DCF valuation, but any DCF implicitly assumes that the free cash flow a business throws off each year is available to the owners. This is typically not the case, and management teams often end up destroying value by reinvesting cash at unattractive rates of return.

How to Value a Business in Real Life?

If discounted cash flow analysis provided a practical answer to how to value a business, investing would be akin to accounting: apply the rules, make some minor judgments, and you would know the value of a business. In such a world, market volatility would likely be quite a bit lower, as investors would be able to ascertain quite consistently the intrinsic value of businesses. Unfortunately, the three DCF assumptions outlined above have proven highly unrealistic in the real world. What confidence do you have in your estimate of the cash flows of a business one, three or five years out? Consider how often public companies surprise investors with quarterly earnings reports. The latter refer not to the future, but to a three-month period that has just concluded. If investors cannot even figure out what cash flows a business generated in a recently concluded period, can they really be expected to make estimates into perpetuity with any confidence?

The most successful practitioners of value investing have long abandoned DCF analysis as a practical valuation tool. Instead, they use several key valuation ratios. The latter are not simply mechanical measures obtained from a database of historical data. Instead, the valuation ratios typically used by great investors incorporate some level of judgment and forward-looking estimates. The difference to a DCF analysis is that the judgments applied to the following valuation ratios can be made with some confidence by the informed investor.

Valuation ratios are sometimes criticized as overly simple answers to how to value a business. Yet, if used correctly, valuation ratios represent one of the most powerful valuation tools available to equity investors. We highlight below the uses and misuses of each valuation ratio, as correct application of any financial metric can mean the difference between signal and noise. A general caveat that applies to all valuation ratios involves special situations or sum-of-the-parts investments. Valuation ratios tend to be most appropriate when valuing going concerns that are fairly monolithic.

How to Value a Business: Price to Normalized Earnings

Calculation: stock price divided by normalized EPS, or recent market value divided by normalized net income

Uses: The use of a normalized earnings figure overcomes some of the shortcomings of the basic P/E ratio, which typically relies on trailing earnings or consensus estimates of this years or next years earnings. Think of normalized earnings as the profit a company might be expected to generate in normal times, i.e. without the benefit of a particularly strong cyclical trend, or without the drag of temporary business underperformance. A mechanical way of estimating normalized P/E is the ten-year earnings average used in Robert Shillers P/E ratio, sometimes also called the cyclically adjusted price to earnings (CAPE) ratio. Other techniques include estimating mid-cycle earnings by examining the earnings trend through past cycles. For non-cyclical businesses, we may estimate normalized earnings as trailing earnings excluding special items. In order to determine the fair normalized P/E, we may examine comparable company valuations or invert the normalized P/E to arrive at the normalized earnings yield. We then compare the resulting percentage yield with prevailing interest rates and the yields available on similarly risky investments.

Misuses: The use of normalized earnings involved an element of judgment. If we get too excited about a business, we may overestimate normalized earnings, potentially prompting us to overpay for a business. On the other hand, if a business has seen negative news flow or analyst downgrades, we may feel tempted to use overly conservatives assumptions in estimating normalized earnings. This may make it difficult to adopt a contrarian stance against the herd. Another misuse of the normalized P/E ratio relates to the drawbacks of the earnings figure. Accrual earnings can differ materially from so-called owner earnings for some businesses, especially those that record large depreciation and amortization but do not have similarly large capital expenditures. In this case, the earnings figure would understate true profitability. On the flipside, some businesses accrue earnings long before the associated cash is received. Businesses may also have disproportionately large capex requirements. In both cases, GAAP or IFRS earnings may overstate owner earnings. Finally, for companies with large holdings of net cash, investors may wish to subtract a large portion of net cash from market value, while also subtracting associated interest income from net income. This will provide a more accurate view into the operating P/E ratio.

How to Value a Business: Free Cash Flow Yield

Calculation: free cash flow divided by market value (adjusted for net cash and special items, if appropriate)

Uses: When thinking about how to value a business, many value-oriented investors prefer free cash flow to accrual income. Free cash flow is typically calculated as operating cash flow minus capital expenditures. It tends to approximate Warren Buffetts notion of owner earnings, i.e. the earnings an owner could remove from a company each year without impairing the competitive position of the business. Value investors often use trailing free cash flow due to the lack of ambiguity involved. However, the use of normalized FCF may also be appropriate, especially when normalized cash flow can be estimated with some confidence and when it differs materially from trailing FCF. Cash flow yield is a percentage figure that can be easily compared to the yields available on competing investments.

Misuses: One of the key advantages of accrual income is the implicit adjustment for the timing of cash flows. If a business performs a service or ships a good in a certain period but does not receive a payment until a few days after the conclusion of the period, it seems appropriate to match up the provision of the good or service with the related cash inflow. Due to a lack of adjustment for the timing of cash inflows and outflows, free cash flow tends to be more volatile than net income. As a result, investors who rely blindly on FCF may either materially over- or underestimate business value. Another misuse of FCF is to assume that an FCF figure calculated by management is congruent with true FCF. Companies sometimes exclude certain items from their FCF calculation, thereby boosting the resulting number. As a result, its important to scrutinize any FCF calculation and decide for ourselves whether it makes sense.

How to Value a Business: Enterprise Value to EBIT

Calculation: (market value plus net debt) divided by earnings before interest and taxes

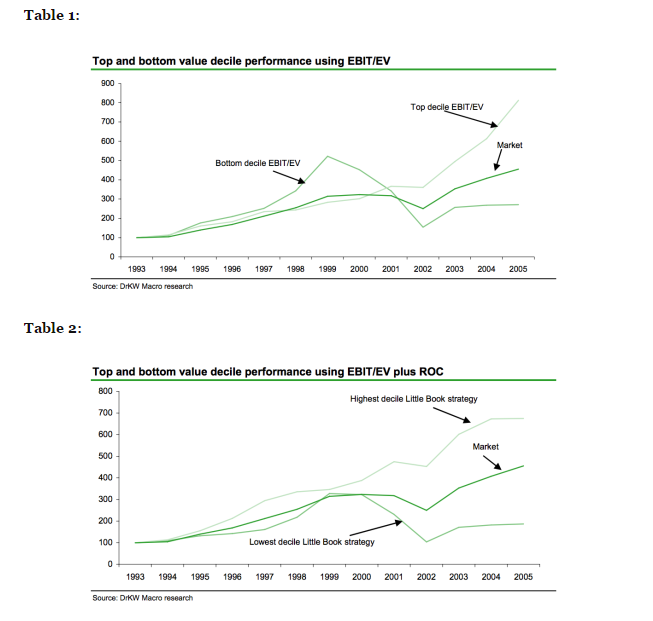

Uses: As with net income and free cash flow, we use EBIT as a measure of the profitability of a business. The key advantage of EBIT is the normalization of earnings to exclude the use of financial leverage and the impact of taxes. This makes it easier to compare valuation ratios across companies with different levels of leverage and different tax rates. Income tax rates tend to be mean-reverting. When we use EBIT instead of net income, we implicitly punish companies with abnormally low tax rates, while paying greater attention to businesses that may temporarily be paying an unusually large amount of taxes. Eliminating financial leverage by excluding interest expense while at the same time using enterprise value instead of market value lessens the need to consider financial risk when comparing the equity valuations of businesses. We therefore implicitly punish companies using large amounts of debt, an appropriate stance for most value investors.

Misuses: In the enterprise-value-to-EBIT formula, the elimination of interest expense in the denominator is balanced by the addition of net debt in the numerator. However, no similar offset is made for the elimination of income tax expense. As a result, our estimate of fair enterprise value as a multiple of EBIT should typically be considerably lower than our estimate of fair equity value as a multiple of net income. As value investors, we may only rarely be willing to pay a double-digit multiple of EBIT to own an enterprise. The multiple should be even lower when it comes to another popular measure of earnings, EBITDA. Finally, in the case of financially distressed companies, we may not be able to dismiss leverage simply by using enterprise value instead of market value. When a business is in danger of equity dilution or bankruptcy, it makes sense to switch to a scenario-based rather than a multiple-based valuation approach.

How to Value a Business: Enterprise Value to Revenue

Calculation: (market value plus net debt) divided by trailing net revenue

Uses: When thinking about how to value a business, the use of enterprise value to revenue represents a crude measure that is useful mostly in conjunction with other valuation ratios or as a mere indicator of potential undervaluation. Rarely will the EV-to-revenue ratio give us a high-conviction point estimate of the value of a business. Instead, it may nudge us toward businesses that could be undervalued on a normalized earnings basis, i.e. assuming future margin expansion. Companies with the lowest EV-to-revenue ratios tend to be those with the lowest profit margins. Frequently, these are businesses that have little margin expansion potential, such as distributors or retails, for whom low margins are part of the business model. However, occasionally, an EV-to-revenue screen will throw up businesses with temporarily depressed margins. If we can gain confidence that margins will revert toward their historical mean, we may be able to make a compelling valuation case. The latter will typically involve the use of a normalized P/E multiple or normalized FCF yield.

Misuses: Investors in fast-growing industries sometimes use EV to revenue as a key measure of business value. If a fast-growing business is not yet earning money, or earning very little money, using revenue as the primary input may be the only way to justify a valuation meaningfully above zero. The fact that revenue may be the only available financial measure does not automatically justify its use, however. Another caveat applies to businesses that earn low margins as a matter of course. Most grocery retailers will typically maintain low EV-to-revenue ratios. Yet, those low ratios will not necessarily signal a discount to fair value.

How to Value a Business: Enterprise Value to Gross Profit

Calculation: (market value plus net debt) divided by trailing gross profit

Uses: This ratio is quite similar to enterprise value to revenue, with the likely benefit of excluding low-gross-margin businesses from consideration. We therefore eliminate a key drawback of the EV-to-revenue ratio: the inclusion of businesses such as distributors, grocery retailers, and low-value contract manufacturers.

Misuses: The drawback of this ratio versus the EV-to-revenue measure is that we give up a component of the margin improvement potential implicit in an EV-to-revenue screen. Specifically, we no longer look for companies with temporarily depressed gross margins. Rather, the companies that rank highly on an EV-to-gross-profit screen likely exhibit normal or even above-normal gross margins.

How to Value a Business: Price to Tangible Book Value

Calculation: recent market value divided by (shareholders equity minus goodwill and other intangibles)

Uses: Price to tangible book value differs fundamentally from the valuation ratios shown above. Tangible book value relies on balance sheet data rather than income statement or cash flow data to help us figure out how to value a business. Income and cash flows are generated from the use of tangible and intangible assets, making the amount and quality of such assets relevant to a valuation exercise. Value-oriented investors often conservatively use tangible book value instead of total book value as a way of disregarding intangible assets that may have become impaired. The latter is frequently the case with companies that trade at bargain-basement valuations. While in a pessimistic scenario goodwill and intangible assets may need to be written off completely, tangible assets can typically be sold at some percentage of their carrying value. Cash and receivables may be worth close to their balance sheet values, while inventories and equipment may require material write-downs. Companies that trade substantially below tangible book value may be undervalued, at least according to net worth as based on generally accepted accounting principles.

Misuses: The use of price to tangible book value will not be appropriate in the case of high-quality businesses that employ little capital. Investors who rely on tangible book value as a primary measure of value will consistently pass on businesses with the most attractive reinvestment characteristics, as such businesses will very rarely be available at prices approaching tangible book value. Another misuse involves highly leveraged businesses, as distressed equities frequently trade at a discount to tangible book value. However, when the capital structure of such companies is viewed in totality, the discount to carrying value becomes much smaller. Occasionally, leveraged equities will offer no bargain investment opportunity regardless of the magnitude of the discount to tangible book value.

How to Value a Business: Market Value to NCAV

Calculation: market value divided by (current assets minus total liabilities)

Uses: This is the second balance sheet-based valuation metric on this list and also typically the most conservative measure of the value of a business. The use of net current asset value (NCAV) will usually tell us little about how to value a business. However, if we wish to estimate the worst-case value of an equity, i.e. assuming liquidation or something close to that scenario, NCAV may prove quite useful. The father of value investing, Ben Graham, is credited with showing how to use NCAV in our search for so-called deep value equities. By buying companies for less than NCAV, we assemble a portfolio of businesses that may not lose us money even if the need to be liquidated. On the other hand, if their business operations improve, we enjoy significant upside potential. An advantage of using NCAV versus tangible book value is the treatment of leverage. By subtracting total liabilities from current assets, an NCAV-based screen will typically eliminate heavily indebted companies, leaving us with financially sound investment candidates.

Misuses: NCAV is almost never an appropriate way of valuing a business. In most cases, an NCAV-based valuation will understate true value by a large margin. As such, NCAV should not be applied to going concerns with some value beyond their tangible assets. Even in the case of capital-intensive businesses, NCAV will be inappropriate except in the case of low-return or money-losing businesses.

How to Value a Business: Going Beyond Valuation Ratios

Valuation is at least as much art as it is science. I would be remiss not to acknowledge the soft factors that enter into any valuation exercise. Numerous excellent books have been written on valuation, including Aswath Damodarans Investment Valuation . so clearly this article is too short to be comprehensive. I deliberately focused on valuation ratios as one of the answers to the question of how to value a business.

Virtually all investors utilize valuation ratios in some way as part of their investment process. Knowing the major uses and misuses of each valuation metric becomes crucial to making the right investment choices. As such, I hope youve found this article a helpful guide. To see most of the above valuation ratios applied in real-life screening for value ideas, enter The Manual of Ideas Members Area .