Value Averaging Spreadsheet

Post on: 4 Май, 2015 No Comment

While the goal of most investors is to buy low and sell high, some of us have the uncanny knack of doing just the oppositebuying at the very peak and selling at the very bottom. The market moves up and down, and very few investors have demonstrated the ability to consistently predict where it is headed over a long period of time. For someone looking to commit a large amount of money to the market, the specter of another market correction can be a disturbing thought. However, history has shown that sitting on the sidelines can be even more destructive, as we miss out on the superior long-term returns of the stock market.

One way to counteract the fluctuations of the market, thereby reducing timing risk, is to follow a formula strategy that mechanically guides your investing. Perhaps the best-known formula plan is dollar cost averaging, whereby you invest a fixed dollar amount in an asset at equal intervals over a long period. As a result, more shares of a stock or mutual fund are purchased when prices are relatively low, while fewer shares are purchased when prices are relatively high. Over time, this strategy can lead to a lower average per-share cost, which, in turn, increases the rate of return.

In the August 1988 AAII Journal, Michael Edleson introduced an alternate concept to dollar cost averaging called value averaging. Instead of investing a fixed dollar amount each period, you set the value of your investment holding to increase by a fixed amount or percentage each period. If share price increases alone cause the total value of your investment to increase above the planned periodic fixed increase amount, you must sell shares instead of adding to the investment. This investment accumulation strategy, which Edleson expands upon in his book Value Averaging: The Safe and Easy Strategy for Higher Investment Returns (John Wiley & Sons, 2006), is more flexible than dollar cost averaging, has a lower per-share purchase cost, and tends to have a higher rate of return.

In this installment of Spreadsheet Corner, we revisit a value averaging spreadsheet developed in the July/August 2001 issue of CI by John Markese, former AAII president, and John Bajkowski, AAII president and former editor of Computerized Investing.

Dollar Cost Averaging Versus Value Averaging

Compared to dollar cost averaging, value averaging is a more aggressive approach because it forces you to invest more money when the market is falling and the total value of your holdings is decreasing. When the value of your holdings goes up, you invest less money buying the higher-priced shares, and there is the potential that you may need to sell shares.

Choosing an appropriate long-term time horizon is key to successfully implementing an averaging strategy. Choosing a longer horizon will help you avoid the potential disaster of investing a substantial portion of your portfolio in the market at its high point. At a minimum, take two yearsinvesting monthly or quarterlyto complete your move into the market. More patient investors may choose a longer period, perhaps as long as five years.

Investors who do not already have a significant pool of cash but do have cash periodically available are spared the temptation of rushing into the market all at once. While such investors are perfectly positioned for an averaging strategy, they may never start an investment program without a system such as this.

Lastly, the frequency of your investments must be taken into consideration. Investing often enough over a uniform time interval is important. Quarterly or monthly investments are reasonable. Investing more frequently, such as weekly, is probably overkill, while investing less often is too infrequent and possibly defeats the benefits of diversifying over time in an ever-changing market.

Comparing the Strategies

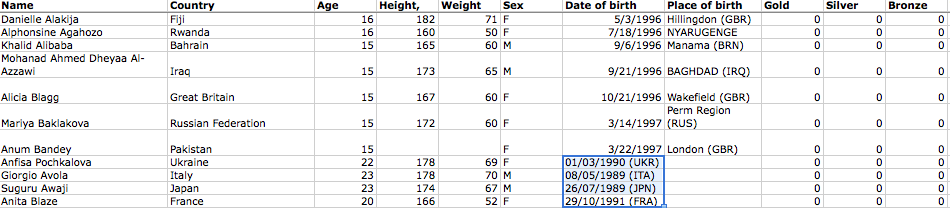

Table 1 compares dollar cost averaging to value averaging, illustrating the structure of each investment plan and highlighting their differences. We used the PowerShares QQQ exchange-traded fund (QQQQ). which tracks the NASDAQ-100 index, a listing of the 100 largest non-financial stocks listed on the NASDAQ Stock Market. The time period covered is the last 24 months, March 2, 2009, through March 1, 2011; the investment frequency is monthly. Keep in mind that these averaging techniques can be used to invest in individual stocks and closed-end mutual funds as well.

We ignored dividend and capital gains distributions to simplify the presentation, but for investors the reinvestment of all dividends and distributions should be part of any investment plan.

Table 1 uses a $1,000 initial investment coupled with a $500 monthly contribution for the dollar cost averaging approach: $500 is invested on the first trading day of each month at the prevailing price of the exchange-traded fund (ETF) .

For the value averaging approach, the same $1,000 initial investment is used along with a $500 monthly increase in value: The amount actually invested each month varies such that the total value of our investment increases by $500 each month; if the share price increases enough to cause the total value of our holdings to increase by more than $500 during the month, we would sell shares to hold the increase in value to $500 for the period. For example, in July 2010 QQQQ shares jumped in price from $42.54 to $46.51. To keep the increase in value for the month to $500, the following calculations must be made: At the beginning of August, before any changes were made to the portfolio, the investor held 211.57 shares of QQQQ at a price of $46.51 per share. Between July 1, 2010, and August 2, 2010, the price increased $3.97 per share ($46.51 $42.54) or roughly $840, $340 more than the planned $500 increase for the month. Therefore, 7.308 shares ($339.93 divided by $46.51) need to be sold.