Use Breakup Value To Find Undervalued Companies_1

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By the time we hear the term breakup value mentioned about a company, things tend to be going pretty badly. It’s often brought up as a throw-in-the-towel response to poor performance, either by the company itself or simply in the price of the stock. However, the theories behind breakup value can be used to evaluate certain types of companies, regardless of their financial health. Any good stock analyst or fund manager will calculate a breakup value for any company that warrants it — namely, any publicly-traded company that operates in more than one distinct business and derives its value from multiple sources. Read on to learn how to calculate and evaluate this valuation measure for yourself.

What Is It?

Most generally defined as a sum-of-parts value, breakup value tells us how much a company would be worth to shareholders if it were stripped down and sold off in pieces. In a true company breakup, the assets are sold, the outstanding debt is paid off with the proceeds and whatever is left is then returned to shareholders. The middle ground that investors most often see is that some business lines are sold for cash, while others are spun off into new companies. For any business divisions that are spun off, the investor will typically get shares in the new company as compensation, or possibly a blend of stock and cash. (For more insight, see Conglomerates: Cash Cows Or Corporate Chaos? )

Events That Cause a Discussion of Breakup Value

- There is a liquidity crisis at the company: Even if only one division is running losses, the cash drain will affect the entire company and keep other divisions from getting the capital and attention they deserve. (For how to determine company liquidity, see The Working Capital Position .)

When Breakup Value Will Not A pply

Many companies, especially those with smaller market capitalizations. tend to be narrowly focused in their business efforts. Companies at this stage are still fighting for market share and looking to establish leadership in the industry. Investors shouldn’t expect these companies to branch out too far.

Using the Theories of Breakup Value

According to the efficient market hypothesis. the price of a stock should, in any given moment, reflect the sum of a business’s parts. In reality, there are many instances in which a company will trade at a discount to its breakup value. In fact, it is not uncommon for a stock to trade at levels below the breakup value for extended periods of time. (For more on this topic, read What Is Market Efficiency and Working Through The Efficient Market Hypothesis .)

Take Stock of the Company as a Whole

The best place to begin a breakup value analysis is by looking at the parent company as a whole. Get a feel for the overall market capitalization, cash and debt levels, and the relative sizes and functions of the operating divisions. Does one division contribute the lion’s share of revenue and earnings? Essentially, you’ll want to look at each division as its own company. If its stock traded on an exchange, what price would it have? The larger a company is (in terms of market cap), the more likely it is that it will have stock spin-offs should a breakup or divestiture occur. Smaller companies will tend to have breakups involving liquidations or cash sales, because the size of the different businesses might not be large enough to trade on the exchanges.

Whenever possible, you should look at competing companies to see what kind of price/earnings valuation range you could expect if a business division were broken out. Take a look at the stock prices of companies that do similar things. You’ll be able to see a pattern emerge in terms of valuation. From this point, you can comfortably apply an average valuation multiple to the business segment, provided that everything else at the company looks roughly equivalent.

To estimate earnings at the division, usually the best measure to use is operating earnings. as opposed to net earnings. Net earnings figures by operating division can be difficult to find because publicly available financial statements tend to only show consolidated results. Operating earnings get to the core of the business, which is the most important consideration at this point. In most cases, we can track down revenue, margins and contributions to income by looking at the company’s quarterly earnings statements (available via the SEC Edgar website).

Cash and investments are liquid assets and should be counted as such. But investors are also seeing more cases of companies owning stock in a peer or partner as a by-product of past relationship-building activities. Be sure to look through the balance sheet carefully so that you can count the value of any of these assets that would be sold off in the event of a breakup.

It is also helpful to read industry press releases to get a sense of what the going market rate is for similar businesses when they are sold.

Example — Time Warner

Time Warner Inc. a company with roots in traditional media, branched out into cable assets and distribution, which brought the company toward the technical forefront of the internet bubble in the late 1990s. As the market set new highs each day, in January of 2000 news broke of the largest corporate buyout in history — the AOL/Time Warner merger of 2000 (the combined entity has since consolidated its name as Time Warner). This merger has since become the poster child for all the excesses of that entire bull market. Here was AOL using its massively inflated stock to buy an old-line media company with what ended up being paper assets — $160 billion in paper assets, to be exact.

Time Warner investors suffered from this merger as much of the value of the merger was been literally wiped off the books. There are still real companies within Time Warner operating at a high level, but it has been difficult for investors to see this through the public backlash over the merger and deteriorating fundamentals at AOL.

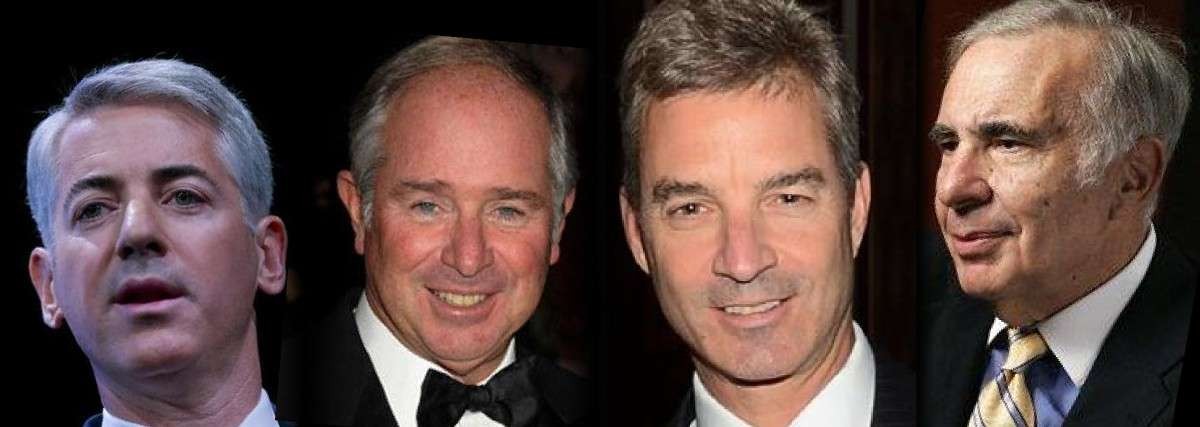

In 2005, Carl Icahn, an American financier with less than 4% of the outstanding Time Warner stock, began pounding the media circuit with calls for Time Warner to split up. As Time Warner’s stock languished at $16-$18 for the third year in a row, Icahn argued that the breakup value for the company was nearly $27/share, as outlined below:

Icahn’s breakup plan looked at Time Warner as four distinct businesses operating under one roof, and examined the scenario in which each was left as a stand alone company.