UBS Gets Whacked by Subprime Mess

Post on: 8 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Staid UBS was blindsided by the subprime dive, leading to big losses and layoffs, but investors are cheered by changes in top management

UBS, which was formed in 1997 when Union Bank of Switzerland was acquired by Basel-based Swiss Bank, has been known since that epoch-making deal as a steadier performer than its accident-prone Zurich rival, Credit Suisse (CS). But suddenly, buttoned-down UBS (UBS) looks like it has gone haywire. On Oct. 1 the bank disclosed that it was writing down $3.4 billion in losses largely due to ill-considered bets on the U.S. subprime market. This, the bank said, would lead to a loss of as much as $683 million for the third quarter when the bank reports its results on Oct. 30. UBS said it would cut about 1,500 jobs, or about 7%, of its investment banking workforce.

Marcel Rohner, who suddenly replaced Peter Wuffli as chief executive (BusinessWeek, 7/6/07) on July 6, also announced the departure of both Huw Jenkins, head of investment banking, and Clive Standish, the chief financial officer, who is retiring. Standish will be replaced by Marco Suter, a former chief credit officer, who had been serving as executive vice-chairman and as a close adviser to the chairman, Marcel Ospel. Suter will leave the board of directors and take up the CFO job as part of sweeping moves by the bank to tighten what seems to have been a flawed approach to risk, especially in the U.S.

Time to Rethink Investment Banking

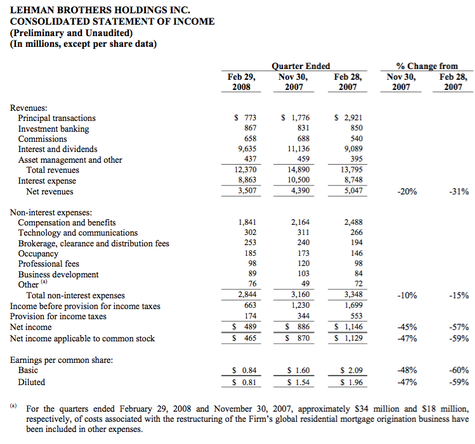

The news prompted a 3.5% rise in the bank’s shares, meaning investors think Rohner is making a serious effort to deal with shortcomings and is being candid about the extent of losses. In addition, European International Financial Reporting Standards accounting rules, with their strict mark-to-market requirements, may be accentuating the bank’s losses, according to Simon Adamson, an analyst at CreditSights, an independent credit research firm. Lehman Brothers (LEH) and Goldman Sachs (GS) recently reported better-than-expected results—but for June through August, not the July through September interval about which UBS is warning, when the impact of the subprime mess began to widen.

Still, the big losses and management turmoil raise questions about whether UBS’s efforts to compete with U.S. rivals such as Morgan Stanley (MS) and Goldman make sense. Once again there will be calls to ditch investment banking and trading—or somehow separate them from the reliably profitable private banking and asset-management businesses that constitute the real bread-and-butter of UBS (as well as Credit Suisse). It’s also questionable whether a major global investment banking and trading operation can be properly managed from the relatively small city of Zurich.

Now Rohner is taking personal charge of investment banking to bring it under control. Credit Suisse has already done much the same. Some 300 to 350 people on UBS’s troubled fixed-income side will be gone by the end of the year, Rohner said. At the same time, he stressed his commitment to investment banking—but even so, UBS is likely to pursue a less risky, less costly model. That may make it difficult, however, to retain top people. Already the bank has lost key operatives, including Kenneth Moelis, who built up the U.S. mergers-and-acquisition business.

Rohner also has brought in Joseph Scoby, who was running the $60 billion quantitative hedge funds business, to head risk management, an area where UBS had potential over-reliance on quite mechanical formulaic approaches, according to Rohner. An American educated at the Wharton School, Scoby came from O’Connor Associates, a well-regarded Chicago derivatives firm that Swiss Bank acquired in the early 1990s.

Reining In U.S. Operations

The latest announcements put Wuffli’s somewhat mysterious middle-of-the-night firing into clearer perspective. What’s emerging is an image of a bank that seems to have lost control of some of its operations, especially its fixed-income business in the U.S. In an interview posted on the UBS Web site, Rohner said the bank had an inventory of $19 billion in subprime residential mortgage-backed securities—90% or more of it rated AAA. He said he was writing down $1 billion on these instruments, which the bank is holding for a better day. He also said that the bank was taking a $900 million write-down on $4 billion of mortgage-backed securities that it was holding in what he called a CDO warehouse, waiting to be packaged up into CDOs (collateralized debt obligations) that are no longer salable.

The impression is that UBS, which has been slower than other banks to cash in on the boom in so-called fixed-income securities, moved in late and then got whacked. Adamson of CreditSights said in a note that UBS’s inventory of subprime notes is huge, presumably reflecting UBS’s rush to capture mortgage business and increase its franchise in the U.S. market. CreditSights also concluded that UBS has been less proactive and/or successful than its U.S. competitors in hedging such risks.

By comparison, CreditSights has a different take on Credit Suisse. The UBS rival said it expects net income for the third quarter to be plus or minus 20% of $1.2 billion. That, said CreditSights, means its asset write-down will be large but within expectations. For once, it is starting to appear a more stable investment bank than UBS.

Dillon Read Unit Implicated

In a revealing statement, Rohner said: Where I see the structural underlying problem is the way we focused a lot on very illiquid, long-dated risk, and at the same time let our balance sheet grow rapidly and provided our funding resource almost freely.…What has happened is that what was historically very safe and low volatility turned through the very serious market dislocation in the U.S. mortgage-backed securities market into a high-correlated credit type of exposure. That’s what happened, and this was not foreseen by our risk framework.

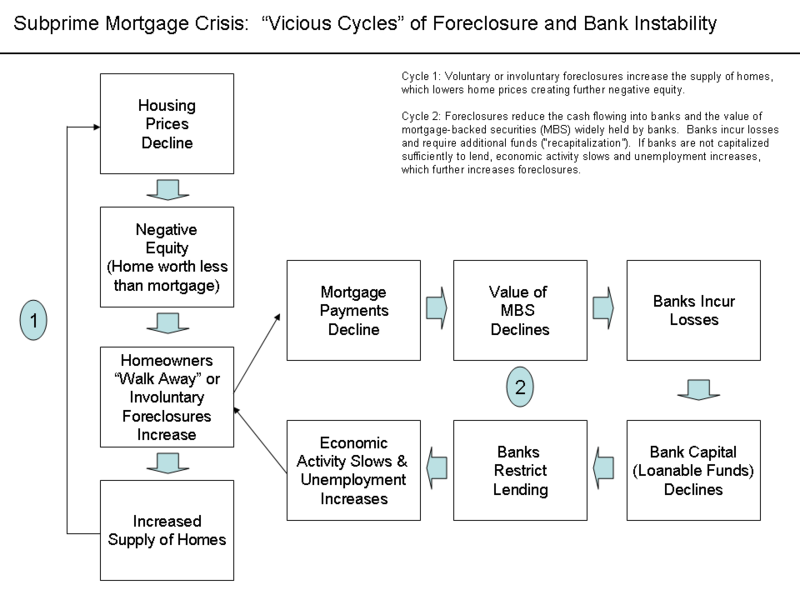

In other words, the bank’s models were not set up to anticipate what would happen if confidence was suddenly lost in these relatively new securities and they were no longer tradable. The origins of this debacle seem to go back to the formation of a hedge fund unit called Dillon Read Capital Management (DRCM) in 2005. This unit was managed by John Costas, the U.S.-based former chief of the investment bank.

The unit was set up as a way of retaining Costas and talented traders, who otherwise might leave for hedge funds. DRCM, which was supposed to manage a combination of UBS and client money, proved a bust in two respects. Cut off from the mother bank, the traders seemed to lose their touch, and DRCM was not very good at attracting outside money. Instead, it stripped talent out of the bank’s fixed-income department and contributed to huge losses.

Before his own ousting, Wuffli in May closed down DRCM (BusinessWeek, 5/3/07) and began folding its operations back into the main bank, with losses and restructuring charges then coming to $420 million. Those losses have grown, though the bank has not yet broken them out from the copious red ink in the rest of the fixed-income businesses. The bank also has taken losses on its relatively modest $13 billion leveraged loan portfolio. While the rumors flew, so far it looks as though UBS was rocked more by the subprime turmoil than anyone else.