Tied to European debt crisis The Washington Post

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By Neil Irwin September 30, 2011 Follow @Neil_Irwin

The political intrigues in Brussels and Berlin over Europe’s debt crisis are as foreign to most Americans as the languages spoken there. U.S. exports to Europe don’t even amount to a fiftieth of what Americans produce. And American banks have at best a modest toehold in the European countries facing possible default.

But the waves of anxiety caused by the European debt crisis are taking a significant toll on the United States — not just palpitations in financial markets but darkening prospects for the broader U.S. economy.

That’s because developments in Europe, like never before, are influencing the judgments of key decision-makers in the U.S. economy: executives deciding whether to add workers or build a new plant, investors deciding where to place their money, even consumers deciding whether to take the plunge on a new house or car.

And today, when they look across the Atlantic, the world seems a lot less safe than it did yesterday.

The U.S. stock market was off sharply Friday, in part because of a discouraging report from Europe showing that German consumers had dramatically scaled back their spending because of fears about the debt crisis. The Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, which fell 2.5 percent on the day, ended the third quarter with its steepest quarterly decline since 2008.

“The world is now a very small place,” said Lynn Elsenhans, chief executive of the giant energy company Sunoco. While a slumping European economy has little direct impact on her company, she said the extreme volatility in world financial markets caused by the European crisis is making Sunoco executives more cautious about investing and hiring.

American Eagle Outfitters, which operates 935 clothing stores in the United States and Canada, has been weighing expanding into Western Europe, according to chief executive James V. O’Donnell. But he said Europe’s situation “gives me real pause for concern. Normally we would be in a big hurry to get to the market, but we’re not in a great rush now.”

On a larger scale, the European crisis also has applied the brakes to the U.S. recovery.

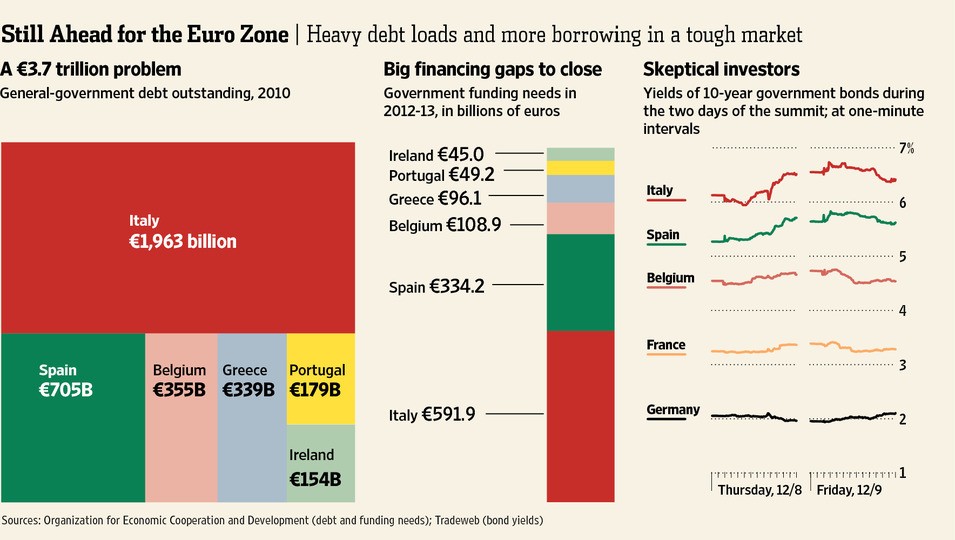

In the spring of 2010, as the U.S. economy was finally starting to emerge from recession with several months of steady growth, concern erupted over Europe’s ability to deal with the debt crisis, which began in Greece and spread to other countries. Global stock prices plummeted. The U.S. economy slowed sharply in the subsequent three months.

Once again this spring, the U.S. economy had regained momentum, recording healthy job growth. But as the European troubles worsened, U.S. job growth again slowed drastically.

The link between economic growth in Europe and the United States is now tighter than in the past. Economists at Citigroup found that the relationship between GDP growth in Europe and the United States was three times closer in the 2000s than in the decade before.

There are several direct ways that developments in Europe can affect the U.S. economy, notably trade. U.S. exports to the continent, while small relative to the overall size of the U.S. economy, still added up to $240 billion last year. That commerce could be endangered if Europe dips back into recession. U.S. multinational corporations, in particular, do extensive business overseas and could suffer real damage.

But Europe’s influence on the U.S. economy also reflects the psychology of global investors.

Increasingly, global markets move in sync, rising or falling together, depending on whether the day’s news offers reason for optimism or pessimism. For example, the U.S. stock market moved in the same direction as the German stock market on 86 percent of trading days this September, in contrast to 68 percent in September 2006.

“The banking sector problems in Europe affect their economic growth, and together that affects the United States. Then over on this side of the Atlantic you have increased risk aversion, and that slows the economy,” said Edward Truman, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “There’s a ping-pong between the real economy and the financial sector, back and forth across the Atlantic and around the world.”

Executives see those effects in the cost of borrowing money to expand their businesses. “The credit markets have really tightened up since things worsened overseas,” said Terrence O’Toole, co-managing partner of Tinicum Capital Partners, a private equity firm that owns companies ranging from makers of parts used in the computer industry to Spanish-language media properties.

And the impact of European turbulence is also apparent to executives in how their customers react to news day in and day out. “It’s a very interconnected world, and it’s an instantaneous effect,” O’Toole said.

The ups and downs of financial markets and ominous headlines from overseas affect customers’ confidence, he said, leading companies to be more cautious about placing new orders for equipment or taking out advertisements.

Most ordinary American consumers aren’t following the dilemmas of Greek debt as closely as corporate CEOs. But Americans do pay attention to their 401(K)s and the general tenor of economic news, and that can weigh on how wide they open their wallets at shopping malls.

“People who come into my stores aren’t thinking consciously about Europe,” said O’Donnell of American Eagle Outfitters. “But to the degree the news is bad, it has a bad impact on demand and weighs on people.”