The Statement of Cash Flows

Post on: 23 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Indicates the sources and uses of a company’s cash

Your e-mail has been sent.

The statement of cash flows is the third principal financial statement (the others being the balance sheet and income statement) that any publicly listed company must make available to investors. It can be found in annual and quarterly reports and is generally audited by an independent accountant.

The cash flow statement shows how cash moves through a business. It reconciles net income, which is a non-cash GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) number, with the actual cash coming into or leaving the business. It shows what the company is doing with its cash, where that cash is from, and how much of it stays within the business at the end of the reporting period.

Unlike the income statement, the cash flow statement does not include non-cash items such as depreciation. This makes it useful for determining the short-term viability of the company, particularly its ability to pay bills. One of the most important features to look for in a potential investment is the company’s ability to produce cash. Just because it reports a profit on the income statement doesn’t mean it is generating sufficient cash. A close examination of the cash flow statement can give investors a better understanding of how the company generates cash and meets its obligations.

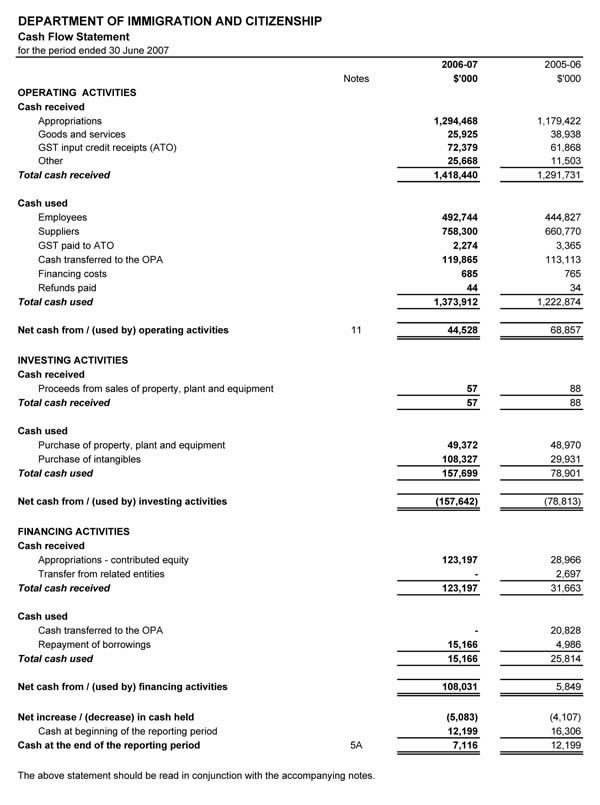

Parts of a Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement is divided into three principal segments: cash from operations, cash from investing, and cash from financing. Note that any negative number represents cash flowing out of the business (such as buying supplies), while any positive number is cash flowing into the business (such as cash collections from customers or taking out a loan)

Cash From Operations is cash generated from day-to-day business operations. This includes all of the cash inflows and outflows associated with doing the work for which the company was established. Most publicly traded companies present this section by adjusting net income to net out non-cash activities such as depreciation, amortization, and adjustments for accounts payable and receivable, among other items. At the end of this section is found net cash from operations, an important number in assessing the company’s overall health (see below).

Cash From Investing represents cash used for investing in assets, as well as the proceeds from the sale of other businesses, equipment, or other long-term assets. The purchase of property, plant, equipment, and other productive assets is classified as an investing activity. Generally, any item that is classified on the balance sheet as a long-term asset would be a candidate for classification as an investing activity.

Cash From Financing is cash paid out or received from issuing and borrowing funds, such as loan proceeds or amounts raised in a debt offering. This section may also include dividends paid, although this is sometimes listed under cash from operations.

The net cash from all three sections is then added up to calculate the net increase or decrease in cash during the period. The statement also shows the beginning and ending cash balance, which ties in with the cash and cash equivalents balance on the balance sheet.

Useful ratios and metrics

Several useful ratios derived from the cash flow statement are frequently used by analysts to help assess a company’s financial health. The most widely used metrics include the following:

Operating Cash Flow/Sales compares a company’s operating cash flow with its net sales or revenues. It gives an idea of the company’s ability to turn sales into cash, in other words, how well the company is at collecting on receivables. Growth in sales without a parallel growth in operating cash flow may indicate future write-offs on uncollectable receivables

Operating Cash Flow/Current Liabilities measures how liquid a firm is in the short run; meaning its ability to meet its short-term obligations. If the operating cash flow ratio is less than 1.0, the company is not generating sufficient cash to pay off its short-term debt — a potentially serious issue that could threaten ongoing operations.

Free Cash Flow. though not technically a ratio, free cash flow is calculated by subtracting capital expenditures from cash from operating activities. It indicates how much cash is left over from operations after a company pays for its capital expenditures (additions to property, plant, and equipment).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a cash flow statement and an income statement?

A cash flow statement shows the actual flow of a business’s cash, while an income statement shows accruals of income and expenses based on GAAP accounting. Managers have more flexibility in booking income and expenses on the income statement — and in determining earnings per share — since they can time the recognition of income and expenses and can accrue and depreciate over different time frames. But the cash flow statement simply shows cash in and out of the business, making it a more accurate picture of actual activity during the period.

What are “warning signs” to watch for when analyzing a company’s cash flow statement?

Negative cash flow, or negative cash from operations, is a sign that the company is relying on financing or asset sales to fund its operations — not a sustainable position in the long run. What’s more, an operating cash flow ratio (operating cash flow/current liabilities) of less than 1.0 is a warning sign that the company may not be generating sufficient cash to pay its bills. Also look for large changes in cash flow from period to period and how they compare with changes to the income statement. If net earnings are holding steady but cash flow from operations is declining, it could be a sign of problems ahead.