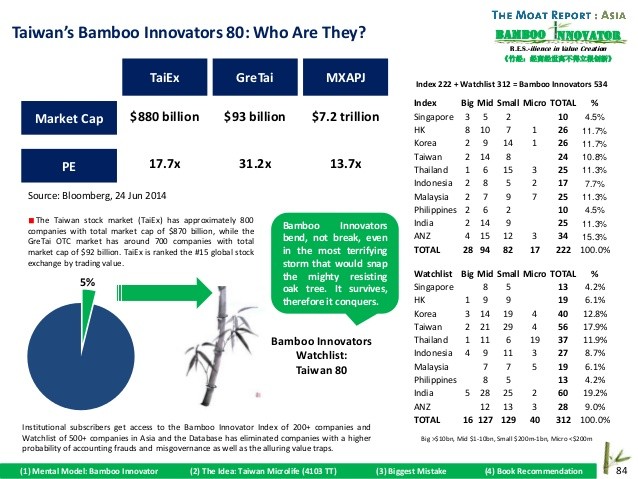

The Moat Report Asia_1

Post on: 30 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

The following article is extracted from the Bamboo Innovator Insight weekly column blog related to the context and thought leadership behind the stock idea generation process of Asian wide-moat businesses that are featured in the upcoming monthly entitled The Moat Report Asia. Fellow value investors get to go behind the scene to learn thought-provoking timely insights on key macro and industry trends in Asia, as well as benefit from the occasional discussion of potential red flags, misgovernance or fraud-detection trails ahead of time to enhance the critical-thinking skill about the myriad pitfalls of investing in Asia at the microstructure- and firm-level.

It was a sight to remember. Almost all hands shot up when asked whether they own a Chinese or Asian stock that has high net cash or net current asset in the balance sheet as a percentage of the market cap. High net cash or net current asset is a Graham-style net-net proxy for “cheap” value stocks with “margin of safety”. The liquidation value acts as the floor to protect downside risk against further price declines, thus providing call-option-like returns as mean-reversion works its magic to realize returns over time for the patient value investor.

That was a presentation made to a group of value investors in May 2010, just before our pilgrimage to Omaha for the Berkshire Hathaway AGM and nearly a year before the outbreak of the Chinese reverse merger scandal in America. There is no mean reversion back to their previous promising growth and valuation levels because the numbers were propped up artificially during good times and the studiously-assessed net-net assets with liquidation value have already been “tunnelled out” and expropriated. So are the audited financial statements of Asian companies unreliable and quantitative analysis of numbers irrelevant? We like to argue that it is the tools and technique need to be adapted to the Asian context. We will be highlighting in a series of articles dissecting both actual and potential companies that have fraudulent accounting and how we can detect them ahead of time.

Most Western-based research and fraud detection techniques focus on the principal-agent (PA) governance problem: the abuse by greedy and power-hungry managers who failed as “agents” in their fiduciary duty to create firm value for the “principal” who are dispersed shareholders. This is different from the principal-principal (PP) problem in Asia in which the abuse is by the controlling shareholder and hence are not adapted to the Asian context. Typical western-based tools on revenue and earnings management include:

- Abnormal accruals analysis: For example, when inventory and trade receivables growth is disproportionately larger than sales growth or when there is a deteriorating trend of Day Sales Outstanding (DSO) or Days in Inventory (DII), such observations point towards possible channel stuffing to book revenue from aggressive business practices or to questionable customers. When accruals turn out to be less persistent than cashflow, the reversal in accruals (e.g. inventory writedown, bad debts) in subsequent period result in negative stock returns, empirical findings that were made famous by accounting researcher Richard Sloan in his 1996 seminal paper that was adapted in various ways by practitioners.

- Remuneration analysis: Performance-based or EPS-linked bonus plans and perks are analyzed to assess whether they distort managerial incentives, motivating managers to act in ways that run counter to the best interests of shareholders, such as manipulating earnings to hit the performance targets to trigger payouts.

These typical tools are inadequate in analyzing Asian companies. As Gavin Grant, head of corporate governance and active ownership strategies at the powerful $740-billion Norwegian sovereign wealth fund NBIM puts it aptly at the IMAS Annual Conference in May 2011, in their decade-plus experience of investing in emerging markets and in Asia, they have learnt painfully that related-party transactions (RPTs) is critical in identifying governance risk in Asia as compared to the West. In Asia, as NBIM pointed out, the fundamental governance problem is opportunism by controlling shareholders through tunneling activities carried out via RPTs at the expense of public minority shareholders such as NBIM who suffer value expropriation. This opinion is later formalized in their influential “Discussion Note 14 ” published in November 2012. Both Harvard Law School and CNBC also pointed out in February 2013 the boldness of the influential decision by the world’s largest and most thoughtful fund to express its dissent on applying western-based Anglo-Saxon governance codes or rules for emerging markets and Asian corporates with a different governance structure.

There are four basic RPT ideas that are prevalently used by many listed Asian companies to escape fraud detection techniques such as the abnormal accruals analysis used by both institutional investors and auditors. A combination of the four ideas is usually employed:

- Deals Potion: Deals potion to extinguish fake receivables that were used to book artificial sales when the receivables are cancelled and the set-off are booked as Goodwill or Intangible Asset that are the premium paid on top of the net book value of the target companies in the “earnings accretive” M&A deal. Target companies acquired using cash are financed externally by debt or equity.

- Grand Capex: Announce some grand net-positive-value expansion projects and inflate capex which goes back as sales and expenses are capitalized to artificially inflate profit margins. Capex projects are financed externally by debt or equity.

- Roll-Away Loans or Advances: Non-trade or Other receivable are loans or advances (usually interest-free) to independent “distributors” or “business associates” which are RPTs that rolled over and never repaid until they are extinguished by either transactions (1) or (2) highlighted above or simply tunnelled out with sudden sales decline during “challenging times” when overall macroeconomic conditions deteriorate. Noteworthy is that the companies would sometimes classify these Other Receivable under Non-Current Assets as amount owing by “Subsidiaries”.

- The Big Push: Push expenses off the listed vehicles to related-party companies to boost artificially-high profit margins and ROE or ROA or ROIC. The listed vehicles are used as “fronts” or “setups” to raise capital from investors during good times or bull market or when the sector is “hot”. These expenses are usually distribution/logistics and selling, general, and admin (SG&A) expenses which are enormous in the geographically-diverse Asian markets. It has been estimated by various sources such as World Bank that logistics cost account for over 15 to 20% of GDP in many emerging Asian countries such as China, India and Southeast Asian nations Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines. For instance, an Asian consumer “brand” selling its “visible” products in supermarkets would usually shift the substantial expenses related to shelf-space placement to related-party “distributors” and achieve the high profit margins and ROE or ROA or ROIC that are attractive to investors.

Thus, one of the quick ways to operationalize the four RPT ideas highlighted above is to check for this possible accounting transgression identity or thumbprint:

DR Other (net) receivables + Other current assets (eg prepayment to “suppliers”) + Other non-current assets (eg amount due from “subsidiaries”)

DR Goodwill or Intangible Asset (if any)

CR Sales (artificial sales)

Since the accounting transaction does not involve trade receivables or inventory, typical abnormal accruals analysis in earnings management will not detect this identity. Also, nearly most databases such as Bloomberg or Factset does not have a separate Other receivables or Other current assets or Other non-current assets dataset for Asian companies that prompt us about their role in these four RPT ideas which value investors can otherwise automate them into our quant screens. The key idea is that revenue is booked only when goods and services are sold to trade customers either on cash or credit terms, NOT when factories are built or when loans and advances are made to “business associates”. But building factories and “loans and advances” result in immediate cash outflow which provide the opportunity for the cash to be easily routed to set-up companies and re-enter the listed companies to be booked as artificial sales.

Having taught accounting for two years at Singapore Management University (SMU) and published an empirical research paper on abnormal accruals (Why ‘Democracy’ and ‘Drifter’ Firms Can Have Abnormal Returns: The Joint Importance of Corporate Governance and Abnormal Accruals in Separating Winners from Losers ), I am personally critical that this may appear overly-simplistic to accounting experts and we are keenly aware of its limitations. But, as mentioned earlier, we will find eerily similar trends and patterns in many of the firms that turned out to be actual fraud cases and also in potential cases whose possible accounting transgressions have not yet unravelled during our decade-plus journey of value investing in the Asian capital jungles.

Case Study 1: Singapore’s Sino-Environment (Peak Market Cap >$850 Million)

Let us dissect the case of now-bankrupt Sino-Environment. a Chinese wastegas-treatment company listed in Singapore in June 2005 that was highlighted by many research houses for its “unique business model”. The securities house of Singapore’s OCBC, rated by Bloomberg as the “world’s strongest bank”, even highlighted the company on a July 24, 2008 report that it is one of “The Resilient Singapore Sevens”. OCBC and fund managers/analysts were excited by the “bulging orderbook” and the environmental issue of polluted air in China. Prominent independent directors are also proxy for good corporate governance. The market cap of Sino-Environment has since plunged from its peak of around over $850 million to zero. Below are the screenshots of the footnotes from the financial reports:

Step 1: Change in sales figures:

2006-07 = +RMB240 million

2007-08 = +RMB312 million

Step 2: Change in Other (net) receivables and Other current assets (Prepayments):

2006-07 = +RMB170 million

2007-08 = +RMB315 million

Step 3: Analyse the capex:

- In FY2008, there is a cash outflow of RMB103 million for “payment for production plant” that does not match the increase in the PPE figure in the balance sheet. This goes into Other current asset as “Prepayment”.

Step 4: Analyze the M&A deals:

- In FY2007, Sino-Environment acquired 60% of a company, with identifiable net assets of RMB89 million, for RMB266 million in cash. Thus, it recorded RMB177 million in Goodwill and net cash outflow from the acquisition is RMB62 million.

- In FY2008, the remaining 40% of the same company is acquired for RMB288 million and the difference between the consideration price and the identifiable net assets is RMB205 million.

FY2007: Notice how RMB176 million in Goodwill is very similar to the change in Other receivables and Other current assets of RMB170 million. Thus, any fake receivables that were used to book artificial sales are now set-off off as Goodwill and Intangible asset in the balance sheet. Also, the cash outflow of RMB238 million (RMB176 million + RMB62 million) possibly to “set-up” companies is potentially re-routed back to be booked as the change in sales for FY07 which is RMB240 million.

FY2008: Notice how the change in Other receivables and Other current assets of RMB315 million is similar to the change in sales of RMB312 million. The cash outflow for the “Grand Capex” and “Deal Potion”, with the corresponding accounting debit entry of Other receivables etc, is possibly routed to setup companies to enter as artificial sales in the listco. The company also raised another RMB710 million in a convertible bond issue.

Interestingly, when we wrote a short newspaper article in Business Times Singapore that was published on Nov 25, 2010 about the case of Sino-Environment, we also highlighted the company’s connection to HK-listed China Green (904 HK). The chairman of Sino-Environment Sun Jiangrong tried to siphon away assets to his private firm and later to a Chinese firm owned by his brother Sun Shaofeng, the chairman of China Green. From the figure below, we are surprised that our article perhaps has some small effects in revealing these RPTs – since Nov 2010, China Green has plunged over 90%.

Case Study 2: Singapore’s China Hongxing Sports (Peak Market Cap >$2.4 Billion)

Now that we are slightly familiar with the accounting transgression thumbprint left behind by the fraud perpetuators, we can go slightly faster in dissecting China Hongxing Sports, the Chinese sportswear brand “Erke” listed in Singapore in 2007 with a peak market cap of over $2.4 billion after raising RMB2.4 billion. Two joint auditors were involved and prominent independent directors were proxies for good corporate governance. Below are the screenshots of the footnotes from the financial reports:

Step 1: Change in sales figures:

2007-08 = +RMB840 million

2008-09 = -RMB890 million

Step 2: Change in Other (net) receivables and Other current assets (Prepayments):

2007-08 = +RMB858 million

2008-09 = -RMB1 billion

FY2008: Notice how the change in Other receivables is very similar to the change in sales. “Advances to distributors” has increased from RMB277 million to RMB1.1 billion to “facilitate the distributors in setting up 358 (FY07: 100) new stores in 21 (FY07: 20) provinces/ cities with the view of expanding the Group’s sales network.” These are essentially interest-free loans and upfront cash outflow that have no immediate impact on sales but provide an opportunity for tunnelling out cash to setup companies who are related parties and rerouted back to be booked as artificial sales in the listed Hongxing Sports. With strong sales growth registered in FY08 and $320 million net cash in the balance sheet, the CEO of the company commented in its annual report: “I believe that if we stay focused on our growth strategy, to continue developing new technologies and designs for our product range and strengthening our brand recognition and prominence, we will be able to ride out this economic downturn and emerge stronger supported by our strong balance sheet and cash position.”

FY2009: The Chinese controlling owner decide to stop “propping” up the listed vehicle and registered a RMB890 million decline in sales. Notice how the Other receivables decline by RMB1 billion and the “Advances to distributors” turned from RMB1.1 billion in FY2008 to become zero in FY2009 and the company claimed that this amount has been “wholly repaid”.

Case Study 3: HK’s Egana and Peacemark

The skeptics will point out that these Singapore-listed Chinese companies have a short listing history since they were mostly listed during the bull market from June 2005 onwards when the Shanghai index was 1,000 which reached the peak of 6,000 in October 2007. Let us quickly look at HK-listed Egana (48 HK) and Peacemark (304), two durable consumer “brand franchises” that were constantly screened out by many quant fund managers with lots of cash in their balance sheet but eventually went bankrupt in an abrupt manner. Egana was listed in 1993 while Peacemark was listed in 1994. Both grew to over a billion in market cap.

Similar to the accounting transgression thumbprint left behind by Sino-Environment and China Hongxing Sports, Egana tunnel out assets by converting and setting-off fake receivables into goodwill via acquisition (“Deals Potion”) and Peacemark tunnel out assets via loans to “business associates” (“Roll-Away Loans or Advances”). Both Egana and Peacemark are savvy fund raising machines and darling stocks as their growth story, simple-to-understand brand franchises and high cash in balance sheet make them highly popular amongst many prominent fund managers.

We are often asked how do we generate our ideas and how do we do our screenings. Is there a systematic and disciplined process and methodology involved? In coming up with the monthly in-depth stock idea in The Moat Report Asia highlighting an undervalued wide-moat business, the proprietary Bamboo Innovator search methodology takes a different screening approach and thought process, by first eliminating and rejecting ideas that don’t fit the mental model:

- Those with a higher likelihood of fraud, governance breakdown and asset expropriation;

- The alluring value traps without a resilient and innovative business model.

Thus, Asian companies with accounting transgression thumbprints such as Sino-Environment, China Hongxing Sports, Egana, Peacemark etc are eliminated in Step 1 of the screening process. This process combines financial data with a wide array of contextual information – including governance analysis, group structure and ownership, related-party transactions, money-go-round off balance-sheet activities, textual/linguistic analysis of the MD&A and news, the “emptiness” business model analysis – and looking through this lens to reach fresh insights in assessing firm value and performance.

There is a happy ending to the hands that shot up when asked whether they own stocks with high net cash or high net current assets as a percentage of their market cap. Some of them, after listening to our presentation in May 2010, shared with us that they had sold out of their compellingly cheap Asian stocks and avoided debilitating losses when the companies turned out later to be involved in accounting frauds Even Norway’s NBIM, the world’s largest and most thoughtful fund, is discovering the critical thinking and technique gap in misgovernance and fraud detection for Asian companies after over a decade-plus experience of investing in Asia; we hope fellow value investors and our subscribers are able to benefit from this hard-won investment insight too.