The Impact of the ‘SayonPay Vote on the CEO Evaluation Process

Post on: 9 Май, 2015 No Comment

The Impact of the ‘Say-on-Pay Vote on the CEO Evaluation Process

Since the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) became law in 2010, one of the hottest topics in the boardroom has been the requirement that most publicly traded companies include in their annual meeting proxy statements a shareholder advisory vote on the approval of the compensation paid to the company’s named executive officers for the past fiscal year.

Called the “say-on-pay” vote, this vote has caused public companies and their advisors to take a closer look at executive pay practices, as shareholders now have the opportunity to voice their objections to those pay practices in a meaningful way.

This article analyzes the impact that the “say-on-pay” vote may have on a particular aspect of executive pay practices, namely the board of directors’ evaluation of the chief executive officer. Specifically, we provide recommendations for conducting, and following through on the recommendations provided by, the CEO evaluation to minimize a company’s potential exposure to “say-on-pay” litigation.

‘Say-on-Pay’ Derivative Lawsuits

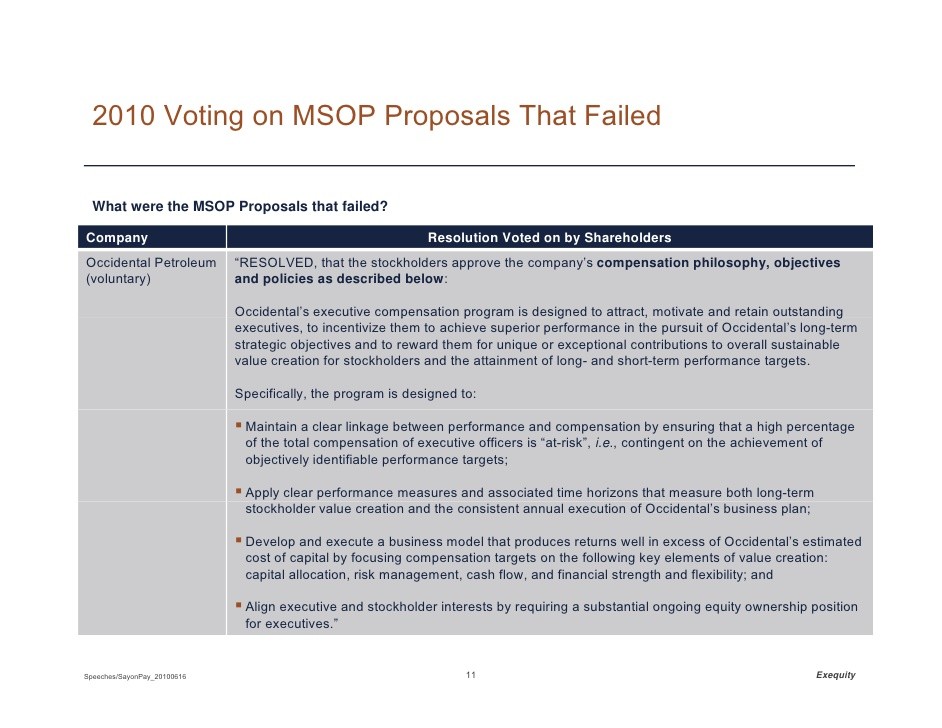

Dodd-Frank provides that the “say-on-pay” vote is of an advisory nature only and specifically disclaims any new or enhanced director fiduciary duties arising from these advisory votes. Nonetheless, at least nine companies to date are facing state law derivative lawsuits following failed “say-on-pay” votes. Other companies with failed “say-on-pay” votes have received demand letters that may result in a derivative lawsuit being filed if a settlement is not reached.

The plaintiffs in these actions generally allege that the company violated its “pay-for-performance” philosophy for compensation by increasing executive compensation in the face of poor corporate performance and that the board of directors disregarded the negative advisory shareholder vote in failing to rescind the increased executive compensation. In some instances, the plaintiffs also allege that the negative shareholder vote itself was sufficient to rebut the presumptive protection of the business judgment rule.

Although many commentators predicted that “say-on-pay” lawsuits would be frivolous, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio recently refused to grant a motion to dismiss filed by the defendant Cincinnati Bell’s officers and directors in the first derivative “say-on-pay” lawsuit.

This has raised a concern that the business judgment rule may not provide as much protection at the pleadings stage for the compensation decisions made by the directors subject to these derivative lawsuits as many had assumed. If the presumptive protection of the business judgment rule were successfully rebutted in a trial, the burden would be on the defendant directors to prove that their compensation decisions and actions were appropriate.

In addition to the pending “say-on-pay” claims, various factors could lead to more failed “say-on-pay” votes, and thus more “say-on-pay” litigation, next year, including a declining stock market and a potentially greater willingness in the second year of “say-on-pay” to fail a company, in the case of institutional shareholders, or to recommend a negative vote, in the case of proxy advisory firms. However, companies can make several changes to the CEO performance evaluation process to help minimize the possibility of a “say-on-pay” derivative lawsuit and position the company more favorably to defend against such a lawsuit.

Formalize the Evaluation Process

The CEO performance evaluation process can take many forms, including interviews of or questionnaires completed by directors, and/or interviews of the CEO and of his or her direct management reports. The process may be overseen by the chairman of the board (if the role of CEO and chairman are separated), the lead director, or the chairperson of the corporate governance committee. The CEO and the directors should agree in advance upon the formal measures on which the CEO will be evaluated, and the measures should be informed by the company’s current strategy, goals, and position in the marketplace, as well as the current corporate environment in which the company is operating.

Establishing and implementing a consistent, formalized, and robust evaluation mechanism to evaluate the CEO’s performance has several benefits for a company’s executive compensation practices.

First, by formally evaluating CEO performance on a regular basis, the board of directors has the ability to build a documented history of CEO performance. This history may strengthen the case for a CEO compensation decision based on longer-term performance despite a “blip” in the company’s performance due to market conditions or other exigent circumstances. Such a history can not only bolster the board’s defense that it has complied with its fiduciary duties in a “say-on-pay” lawsuit, but can also help support the company’s recommendation that the shareholders approve the “say-on-pay” vote if it is articulated clearly and well in the proxy statement.

Second, by conducting CEO performance evaluations on a regular schedule, the board of directors sets a positive “tone at the top” that management performance is regularly tracked and that strong performance is incentivized through pay increases and bonus compensation.

Additionally, by considering the criteria used to evaluate the CEO’s performance with the “say-on-pay” vote in mind, the board has the opportunity to develop an evaluation approach that considers not only financial metrics that may directly impact the shareholders in the short term, but also non-financial areas that benefit the company over the long term. These non-financial areas could include, for instance, creating an acquisition strategy for the company or developing effective executive succession plans.

Align the Performance Metrics

The compensation committee of the board of directors should play a key role in the CEO evaluation process, beginning with the committee’s clear articulation of the company’s “pay-for-performance” compensation philosophy. This philosophy should include details about how the committee measures executives’ performance, focusing on the ways in which strong performance is rewarded and weak performance can be penalized. The compensation philosophy should guide the structure of the company’s compensation plans and programs, the corresponding executive evaluation process, and the resulting compensation decisions.

While the corporate governance committee may officially “own” the CEO performance evaluation process, the compensation committee should be actively involved in the development of the performance measures on which the CEO will be evaluated so that those measures are aligned with the performance measures set under the company’s various executive compensation plans. For example, subjective performance goals within a long-term or annual cash bonus plan should be linked with the strategic and operational measures on which the directors are measuring the CEO’s performance.

Actually Link Compensation to Performance

Once the CEO performance evaluation process has been completed and the results compiled, those results should be reviewed closely and used by the compensation committee to make compensation decisions, including whether to grant a base salary increase, a discretionary bonus, or all or a portion of an annual cash or long-term bonus award to the CEO.

The impact that evaluation results should have on compensation decisions will depend on the company’s individual circumstances. For example, a compensation committee in a position to emphasize performance over all other factors could consider its default position to be that salary increases or certain bonuses will not be paid to the CEO when specific performance metrics set forth in the performance evaluation are not achieved. While this example will not be a practical or desirable outcome of the performance evaluation process for every company, it is important from a “pay-for-performance” perspective that the evaluation process be more than a symbolic exercise; it should significantly impact the committee’s compensation decision-making process.

Communicate Basics to Shareholders

Avoiding a negative “say-on-pay” vote is the surest way to lessen the likelihood of a derivative lawsuit, so it is important to understand what will drive the voting recommendations of Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and other proxy advisory firms, which are followed by many institutional investors. ISS develops policies each year to guide its proxy voting recommendations, and ISS’ evaluation of executive compensation proposals is driven by a set of global principles.

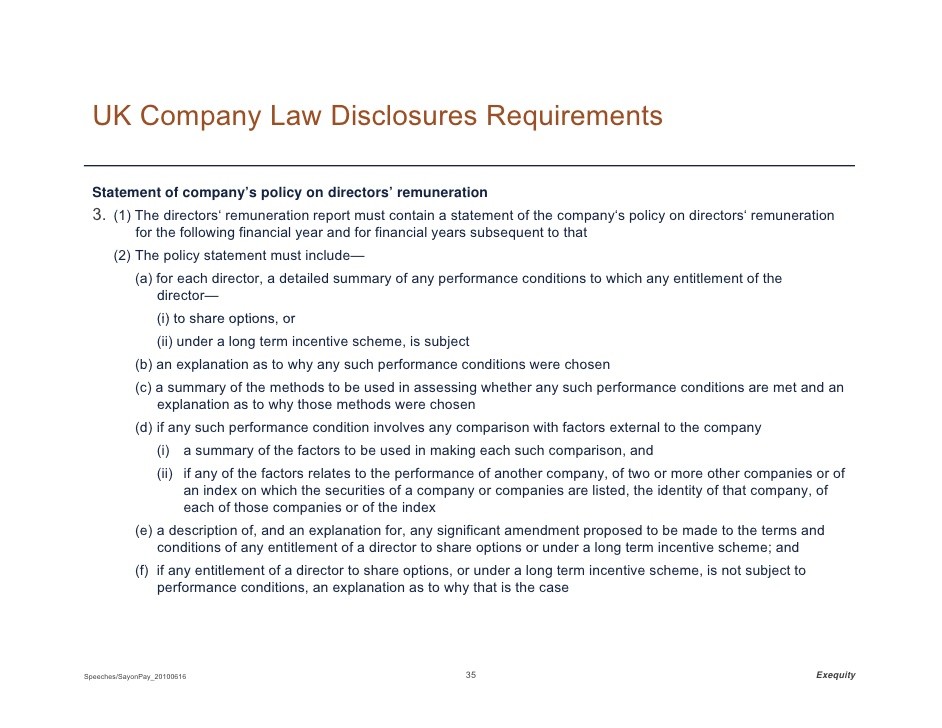

One principle from ISS’ 2011 Proxy Voting Guidelines Summary is that to receive ISS’ support for an executive compensation proposal, companies should “[p]rovide shareholders with clear, comprehensive compensation disclosures.” ISS explains that “[t]his principle underscores the importance of informative and timely disclosures that enable shareholders to evaluate executive pay practices fully and fairly.” Accordingly, companies should ensure that the “pay-for-performance” compensation philosophy developed by the compensation committee is clearly articulated to shareholders and others.

The Compensation Discussion & Analysis (CD&A) and the supporting statement for the “say-on-pay” proposal in the proxy statement are perhaps the most important communications in connection with say-on-pay. While companies have not traditionally highlighted the CEO performance evaluation process as part of their compensation practices in CD&A, the description of how the CEO’s performance evaluation is conducted, including the linkage of his or her performance evaluation metrics to the performance measures utilized under the executive compensation plans, can play an important role in the discussion of a company’s “pay-for-performance” philosophy.

Know What Is Discoverable

In general, if CEO performance evaluations are relevant to a pending litigation, they are discoverable. Even so, there are a variety of steps that can be taken to reduce the likelihood that these evaluations will have to be produced.

For example, some companies choose to involve an outside compensation consultant or other third party advisor in the CEO performance evaluation, who will in turn conduct surveys of directors, a CEO’s direct management reports, and others, and then compile a summary report of the findings for the review of the chairman, the lead director, or a committee of the board. In this situation, the individual reviews are not in the possession of the company, but rather a third party, which means it is more difficult for them to be produced in any litigation.

The third party consultant is also likely to have a simpler document retention policy than a publicly traded company, making it more probable that the individual evaluations will have been destroyed in the normal course long before any litigation occurs.

Any summary report is likely discoverable in litigation if the third party advisor is not an attorney or law firm, as no attorney-client privilege would attach to the report. Having the board retain an attorney or law firm to be involved in the evaluation process, including preparing the summary report, can bolster an argument in litigation that the attorney-client privilege attaches to the survey results, precluding discovery if successful.

If the company is conducting the evaluation process in-house, it should review that process to try to reduce the chances that “raw” survey results will be discoverable. It may be possible for some or all of the individual surveys of the CEO’s performance to be done orally so that only summaries would exist in writing.

It would also be advisable to implement a document retention policy covering such evaluations whereby the actual survey results themselves are not retained once the summary report is prepared and delivered, if such a policy would be consistent with the overall document retention strategy of the company. The company should also review who has access to the survey results and attempt to limit access to the extent possible to reduce the chances that results will remain in someone’s computer even though all results were to be destroyed under the company’s document retention policy.

Finally, all of those involved in the CEO evaluation process should be reminded at the outset that the individual survey results may end up being discoverable in litigation and, consequently, constructive comments (both positive and negative) are preferred and comments of a personal nature should be avoided. These strategies help to ensure that instances of one-off survey responses inconsistent with the overall summary of survey results won’t be discovered and used out of context in derivative litigation to challenge compensation decisions.

Conclusion

There is no silver bullet that will allow a company to avoid a derivative “say-on-pay” lawsuit. While Dodd-Frank purports not to alter the fiduciary duties of a company or its board of directors, the reality is that the heightened shareholder scrutiny resulting from advisory “say-on-pay” votes means that directors are well-advised to reconsider the processes by which they make executive compensation decisions to support the exercise of their fiduciary duties. Thoughtful use of CEO evaluations can play a positive role in enhancing communications concerning executive pay with shareholders and other stakeholders and in lessening the likelihood of negative “say-on-pay” outcomes.

By Jessica Lochmann Allen, Michael Schultz, and Steven Vazquez

Jessica Lochmann Allen is a partner in Foley & Lardner LLP’s Milwaukee office, and is a member of the firm’s Transactional & Securities Practice. Ms. Lochmann practices general corporate and business law, with an emphasis in securities law, corporate governance, and mergers and acquisitions. Michael Schultz is an associate in Foley & Lardner LLP’s Boston office, and is a member of the firm’s Private Equity & Venture Capital, Commercial Transactions & Business Counseling and Transactional & Securities Practices. Mr. Schultz practices general corporate and business law with an emphasis on venture capital transactions, corporate governance, and mergers and acquisitions. Steven Vazquez is a partner with Foley & Lardner LLP’s Tampa office, and is a member of the firm’s Transactional & Securities and Private Equity & Venture Capital Practices. Mr. Vazquez’s practice focuses on securities offerings and other securities matters, corporate governance, mergers and acquisitions, and venture capital transactions.