The higher they rise the harder they fall just as it was in the dotcom boom

Post on: 18 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it was the oft-repeated maxim of philosopher George Santayana. And investors may now be finding out that they ignored the story of the dotcom boom and bust at their peril.

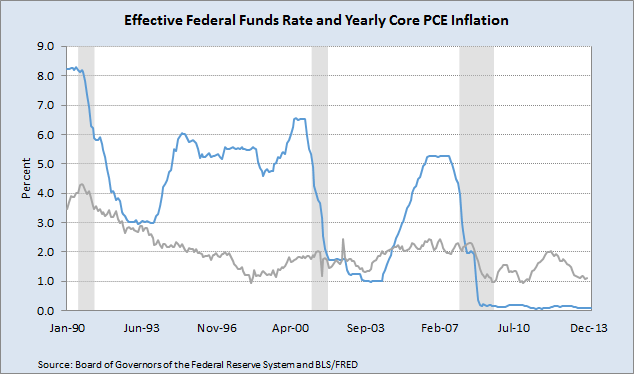

At the start of 2000, shares were at record highs, technology companies could do no wrong, and scores of loss-making internet businesses were racing to market at improbable valuations. But the bubble burst, partly thanks to the Federal Reserve raising interest rates. As a consequence, many companies that had neglected to worry about making a profit simply ran out of cash.

Fast forward to today, and we have seen a new wave of dotcom businesses join the market, even as the US central bank is beginning to rein in the supply of cheap money that has supported stock markets for the past five years. For the lastminute.com flotation of 2000, which turned out to be a perfect signal for investors to start selling, read Just Eat or AO World. or perhaps even lastminute itself, since its current loss-making parent, Sabre Corporation, is planning an imminent $5bn flotation.

For the Fed raising interest rates then, read the gradual trimming – or tapering in the vernacular – of its monthly bond-buying programme now.

So last week we saw the technology-heavy Nasdaq fall by 3.1% on Thursday, its biggest daily decline since 2011. The much-hyped tech stars were among the hardest hit, with Facebook falling 17% from its recent high in April and Twitter losing a quarter of its value over the same period.

In the UK, recently listed Just Eat, Boohoo and AO World were afforded hefty valuations when they made their market debuts, but now stand at or below their flotation prices.

There have been several explanations for the slide, from suggestions that investors were cashing in to pay taxes on their recent gains – also one of the reasons put forward for the March 2000 slide, as it happens – to a realisation that many company valuations were wildly out of kilter with reality.

Jim Reid at Deutsche Bank is probably on the money when he suggests much of the decline is due to the Fed: As it becomes ever clearer that the Fed is pretty much fixed in its determination to stop quantitative easing late this year, the oxygen that has fuelled the five-year bull market is slowly draining out … Those sectors that have done best since the bull market/high-liquidity period started are suffering in the recent correction.

There are other concerns of course. Russia’s actions in Ukraine are also creating uncertainty, with talk of troop buildups and the cutting of gas supplies indicating that the crisis could get worse before it gets better. China is showing signs of a slowdown in growth, albeit from high levels, and this is likely to knock back the global recovery and, in turn, company earnings. Again, businesses with the highest valuations are likely to suffer the most if they struggle to meet earnings forecasts in an economy that is slowing.

As Reid points out, the Nasdaq technology and biotech indices have soared 254% and 281% since the lows of March 2009. Over the same period the broader S&P 500 has risen 177%.

And the recent slump has reflected this. The S&P 500 has lost 3.1% since its peak earlier this month, while the technology and biotech indices are down 5% and 20% respectively.

The pattern is the same in the UK, with the FTSE 350 technology hardware index down more than 8% while the FTSE 100 has fallen by just 1.5%.

So we are not in a bear market: that is defined as a fall of more than a fifth from the most recent peak. And a few days of decline does not mean it is time to call the market turn. But the warning signs are there – and it is a foolhardy investor who pays them no heed while forgetting the past.

Diageo needs more bottle

The film Whisky Galore! sees crafty Hebrideans hide thousands of bottles of holy water from the authorities after a shipwreck disgorges a mountain of single malt. Next week, Scotland’s biggest whisky producer is likely to pull off a similar disappearing act when it comes to the question of independence.

Asked about the subject last year, the former chief executive of Diageo – maker of Bell’s and Talisker – said a go-it-alone vote would make no difference to any decision on investing north of the border. Scotch has been around for hundreds of years, it has seen all kinds of political changes. We’ll weather anything, said Paul Walsh. His successor, Ivan Menezes, has been similarly abstemious in his comments, despite the Scotch Whisky Association joining the debate last week.

Such a laid-back approach to a pivotal moment in Scotland’s future makes you wonder if the board has been nipping at its private Dalwhinnie supply. It is puzzling given the potential consequences of a yes vote on 18 September – an outcome gaining credence among some neutral observers. Standard Life, the Edinburgh financial services group, has warned that it might quit Scotland in the event of a breakaway, while BP said an independent Scotland would almost certainly see it face higher costs and an uncertain investment environment. Following the intervention this month of Glasgow-based industrial giant Weir Group, Diageo’s refusal to engage meaningfully is leaving a significant hole in the debate.

Voters should certainly ask Menezes for a more frank assessment of the economic ramifications. In order to succeed as a standalone economy, Scotland will need a vibrant export industry. With exports of around 3.5bn per year, whisky is second only to oil and gas in sending Scottish goods abroad, while it also supports more than 30,000 jobs in the country.

So Diageo’s insouciance in the face of the thorny monetary-union question is hard to believe. The company owes the country an honest answer on the independence question. Unlike the plot of Whisky Galore!. this is not a jolly caper.

That’s the way the pasty crumbles

Two years ago, David Cameron held one of his most surreal press conferences when a briefing about the London Olympics was hijacked by questions over the pasty tax – George Osborne’s ill-fated budget proposal to impose VAT on hot food.

I am a pasty eater myself. I go to Cornwall on holiday. I love a hot pasty, he said. As his defence of the threatened comestible gathered steam in front of startled hacks, Cameron added that he once bought one of the delicacies offered by the West Cornwall Pasty Company – I was in Leeds station at the time – only for it to transpire that the branch had in fact shut years before. But now that former Leeds footballer Danny Mills has been confirmed as one of the new owners of the chain, he will know where to open a new branch. There is at least one potential repeat customer out there.