The Firm and Financial Statement Analysis

Post on: 29 Май, 2015 No Comment

1.4 Understanding the Firm and Financial Statement Analysis

Financial statement analysis is a set of techniques to analyze the financial performance of a company, to assess its strengths and weaknesses, and to compare it to other firms in the same industry. It provides information about the past and current performance of a company. It is also used to project the future performance of a company. It is used by the company’s managers to improve performance, by analysts who provide recommendations on the company’s stock, by the company’s creditors who decide whether to lend money to the company, and by the shareholders of the company who are interested in the current performance of the company and in whether the company will continue to be profitable. A necessary condition for successful financial statement analysis by an financial analyst is to first understand the business. In the “Conceptual and Practical Skills” topic below we illustrate step-by-step what is really required to understand the business. Item 1 in the 10-K is an invaluable source of information for this purpose. This is because in this item the firm gets to describe their business model and strategy. In this section we work through the operational steps required for unlocking this information from a 10-K. In turn this information provides a framework for interpreting the results from a financial statement analysis.

Financial statement analysis uses the uses the financial reports of a company as its main input. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) describes the objective of financial reporting as follows:

“…… to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to present and potential equity investors, lenders, and other creditors in making decisions in their capacity as capital providers. Capital providers are the primary users of financial reporting. To accomplish the objective, financial reports should communicate information about an entity’s economic resources, claims to those resources, and the transactions and other events and circumstances that change them. The degree to which that financial information is useful will depend on its qualitative characteristics.”

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) adopts a similar, but slightly different, approach:

“…to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful in making decisions about providing resources to the entity and in assessing whether the management and the governing board of that entity have made efficient and effective use of the resources provided. The reporting entity concept is intended to further this objective.”

Conceptual and Practical Skills

Valuation Tutor works directly with company filings. This includes gaining an understanding the language, the aggregations and the classifications actually used by public firms when presenting their accounts. For example, Valuation Tutor lets you quickly compare the current major annual and/or quarterly financial statements filed by some subset of companies that you specify from the SEC’s interactive data.

In terms of developing your conceptual skills in relation to these filings we take the perspective of investors, and so our focus in on understanding how publicly traded companies create value for shareholders. An essential tool in understanding how a company creates value is financial statement analysis, which involves studying the financial reports of a company and learning how to extract information from financial reports.

We start with some basics. A company is owned by its shareholders. In return for investing in the company, the shareholders expect a return. This return can come in the form of dividends, stock repurchases, or capital gains. The higher the return, the greater the value created by the company.

A quote attributed to Warren Buffet asserts:

“Never invest in a business that you do not understand.”

Today this quote is in danger of becoming a cliché, however if you apply the conceptual framework in figure 1, you will gain insight into the quote’s intended original meaning. That is, understanding a business starts with understanding a firm’s business model and then learning how to identify and evaluate a firm’s business strategy. Figure 1 summarizes this process and includes two important tools designed to help you achieve this objective by helping you to gain insight into how business strategy is formulated, communicated and evaluated. These tools are “SWOT” and “Balanced Scorecard” analyses.

Figure 1: Understanding the Business

Overview of Understanding the Business

First, the business model describes how the company builds shareholder value. In order to become better acquainted with the business model we will represent in terms of Porter’s Value Chain which depicts the set of primary value adding activities required by the model. Second, a firm’s business strategy, which describes how a firm implements it’s business model, can also be understood relative to the firm’s value chain. In this case the business strategy identifies which value adding activities are emphasized relative to others. This may imply that some of these activities are outsourced or even eliminated relative to competitive rivals.

Identifying and understanding a firm’s business strategy from an analyst’s perspective, is not easy. In the following sections we approach this problem by providing a set of operational steps that if followed, provide rich insights into identifying and understanding a business from this perspective.

First, it is useful to perform a “SWOT” analysis. That is, an analysis of the Strengths and Weaknesses which are internal to a firm, and an analysis of the Opportunities and Threats that are external to the firm. The external analysis requires an assessment of the degree of competitive rivalry faced by the firm. A SWOT analysis is a key component for formulating strategy because it forces management to consider both the internal and external environments that the firm’s business model is implemented in. Just as SWOT is useful for identifying and formulating a firm’s business strategy, a Balanced Scorecard analysis is a useful tool for communicating and evaluating a firm’s business strategy. We now illustrate these important steps that need to be taken in order to understand a business.

Step 1: The Business Model

The first step is to understand what a company does to create shareholder value. This is called the business model. For example, a company could decide to produce cars, computer chips, or operate retail stores. This information is disclosed in the company’s annual report; and in the United States a publicly traded company must file such a report with the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC’s website summarizes the filing requirements as follows:

“The federal securities laws require publicly traded companies to disclose information on an ongoing basis. For example, domestic issuers (other than small business issuers) must submit annual reports on Form 10-K, quarterly reports on Form 10-Q, and current reports on Form 8-K for a number of specified events and must comply with a variety of other disclosure requirements.

The annual report on Form 10-K provides a comprehensive overview of the company’s business and financial condition and includes audited financial statements.”

www.sec.gov/answers/form10k.htm)

Here are three examples that cover retailing, manufacturing and services, taken from 2010 10-K filings:

• “Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (“Walmart,” the “company” or “we”) operates retail stores in various formats around the world and is committed to saving people money so they can live better.”

• Intel Corporation: “We develop advanced integrated digital technology, primarily integrated circuits, for industries such as computing and communications. Integrated circuits are semiconductor chips etched with interconnected electronic switches. We also develop computing platforms, which we define as integrated hardware and software computing technologies that are designed to provide an optimized solution.”

• IBM Corporation. “The company creates business value for clients and solves business problems through integrated solutions that leverage information technology and deep knowledge of business processes. IBM solutions typically create value by reducing a client’s operational costs or by enabling new capabilities that generate revenue. These solutions draw from an industry leading portfolio of consulting, delivery and implementation services, enterprise software, systems and financing. “

You can see that each of these companies state quite precisely what they do; one operates retail stores, Intel produces computer chips (integrated circuits) and computing platforms and IBM provides innovative solutions that exploit cutting edge technology to their clients.

Representing the Business Model as a Value Chain

An important concept, due to Porter (1985), is called the value chain which is defined from the firm’s business model. This tells you the sequence of activities the company performs so you can see what the firm does; this lets you see where it is weak and where it is strong. For example, think of a bookseller. Given their assets (e.g. the store), the activities will consist of buying books from publishers (procurement), internal operations (receiving the books, putting them on the shelves, paying bills), marketing and sales (advertising, store displays, helping people find books), and customer service (special orders, returns). The activities help you decide what to look for when identifying their business strategy and evaluating their performance. In this example, some the important business ratios are fairly evident: return on assets is a broad measure of profitability, and clearly you would be interested in the average number of days it takes for inventory to turnover.

In Porter’s original formulation a typical chain was depicted as follows:

Since Porter’s original formulation of the Value Chain in 1985, there have been many technological innovations including the emergence of real time databases that have had a profound impact upon value chains. As a result, information flows drive today’s value chains and technology is applied to squeeze out efficiencies that were not available in 1985. For example the rise of Supply Chain Management (SCM) and Customer Relationship Management (CRM) techniques, that exploit real time access to information throughout the entire chain, make the entire chain very dynamic. This has led to some activities initially classified by Porter as support activities, becoming primary activities for some businesses.

For example, in SCM procurement is a primary activity. Similarly, it has also led to the chain truly becoming a “chain.” For example, CRM is designed to maintain ongoing relationships with clients so the links form into a chain. We now consider two examples illustrating these points.

Earlier part of the Item 1 10-K descriptions were provided for IBM and Wal-Mart. Consider, Wal-Mart first. Porter’s generic description is applicable with the following modifications:

Figure 2, A Value Chain for Wal-Mart

Supply chain management is critical to Wal-Mart and as such there is an extended relationship with Suppliers that is linked via databases. Similarly, the Procurement activity is key to Wal-Mart for supporting everyday low pricing. This is reinforced in Wal-Mart’s 10-K when describing their executive officer titles (Item 4):

“Executive Vice President, Chief Information Officer. From February 2003 to April 2006, he served as Executive Vice President, Logistics and Supply Chain.”

On the other hand Customer Relationship Management is important to IBM and their value chain will look very different to Wal-Mart. For example procurement is not an important activity to IBM.

Figure 3: A Value Chain for IBM

Becoming acquainted with the company’s Business Model at the above level is an important necessary step that facilitates identifying and understanding a company’s business strategy. The best starting place for becoming acquainted with a firm’s business model and business strategy is the firm’s 10-K, and Valuation Tutor makes this immediately available to you by entering the stock ticker.

Once you are able to represent a firm’s business model in terms of a value chain you are now in a position to become acquainted with the firm’s business strategy.

Step 2: Business Strategy

The second step is the business strategy. This summarizes how the company intends to implement its business model to create shareholder value. One way you can think of the difference between the business model and the business strategy is that the model is what it wants to do to create shareholder value and the strategy is how it plans to do it. An important part of the strategy is how it plans to compete with other companies and as such, the degree of competitive rivalry a firm faces is the major driver of the design of a firm’s business strategy. For example, business strategy is not important to a gold miner whereas it is most important to a Wal-Mart, Intel or an IBM as again the 10-K report reinforces. For our three examples Item 1 contains the following:

• Wal-Mart: “We earn the trust of our customers every day by providing a broad assortment of quality merchandise and services at everyday low prices (“EDLP”) while fostering a culture that rewards and embraces mutual respect, integrity and diversity. EDLP is our pricing philosophy under which we price items at a low price every day so our customers trust that our prices will not change under frequent promotional activity”

• Intel Corporation: “We design and manufacture computing and communications components, such as microprocessors, chipsets, motherboards, and wireless and wired connectivity products. Our platforms incorporate software to enable and advance these components. We strive to optimize the overall performance of our products by improving energy efficiency, seamless connectivity to the Internet, and security features. Improved energy efficiency is achieved by lowering power consumption in relation to performance capabilities, and may result in longer battery life, reduced system heat output, power savings, and lower total cost of ownership. Increased performance can include faster processing performance and other improved capabilities, such as multithreading, multitasking, and processor graphics. Performance can also be improved by enhancing interoperability among devices, storage, manageability, utilization, reliability, and ease of use.”

For the case of IBM they explicitly discuss strategy in Item 1 of their 10-K, under the heading Strategy:

IBM Corporation: STRATEGY

“ Despite the volatility of the information technology (IT) industry over the past decade, IBM has consistently delivered superior performance, with a steady track record of sustained earnings per share growth. The company has shifted its business mix, exiting commoditized segments while increasing its presence in higher-value areas such as services, software and integrated solutions. As part of this shift, the company has acquired over 100 companies this past decade, complementing and scaling its portfolio of products and offerings.

IBM’s clear strategy has enabled steady results in core business areas, while expanding its offerings and addressable markets. The key tenets of this strategy are:

• Deliver value to enterprise clients through integrated business and IT innovation

• Build/expand strong positions in growth initiatives

• Shift the business mix to higher-value software and services

• Become the premier globally integrated enterprise

These priorities reflect a broad shift in client spending away from point products and toward integrated solutions, as companies seek higher levels of business value from their IT investments. IBM has been able to deliver this enhanced client value thanks to its industry expertise, understanding of clients’ businesses and the breadth and depth of the company’s capabilities.

IBM’s growth initiatives, like its strengthened capabilities, align with these client priorities. These initiatives include Smarter Planet and Industry Frameworks, Growth Markets, Business Analytics and Cloud Computing. Each initiative represents a significant growth opportunity with attractive profit margins for IBM. “

Again, the three strategy descriptions illustrated above for Wal-Mart, Intel and IBM, are fairly simple: one strives for consistently low prices, one strives to improve performance, and the third innovates and transforms these innovations into providing solutions for their clients. It is clear that if each of these entities perform these tasks well and better than their competitors, they will build shareholder value.

Business Strategy and the Value Chain

Observe in the previous topic on Business Model that the set of major value adding activities are identified, but there was no attempt to identify what relative weighting was placed on each of the activities. For example, consider the following value chain that is equally applicable to two competitive rivals, Coca Cola and PepsiCo:

Figure 4: Value Chain for Coca Cola and PepsiCo.

From a business strategy perspective prior to the fourth quarter of 2010 these two companies placed very different weights on these activities. Coca Cola outsourced Outbound Logistics whereas Pepsico retained outbound logistics. This difference abruptly changed when Coca Cola announced on February 25, 2010 that it had agreed to acquire the North American bottling plants. From the perspective of the above chain this placed weight upon Outgoing Logistics plus it also placed increased weight upon Sales and Marketing because now Coca Cola had much quicker access to local information and flexibility to match regional promotions run by PepsiCo in local supermarkets and other outlets.

From an operational perspective, Business Strategy can be defined directly in terms of the activities on a value chain. In particular, strategies tend to fall within one of three types. A firm may choose to perform:

i. Different activities to their rivals

ii. The same activity in different ways

iii. Choose not to perform an activity

For the case of our Coca Cola and PepsiCo example, prior to 2010 they competed in terms of iii. but this placed Coca Cola at a disadvantage to PepsiCo in terms of their marketing and sales. That is, they lacked the flexibility and the real time information provided from controlling the bottling and distribution operations at a regional sales and promotions level. Post the acquisition, the competitive strategy intensified with respect to Marketing and Sales activity ponce Coca Cola has control over these elements of the value chain.

Similarly, for the case of i, above, Amazon and Wal-Mart are competitive rivals but Amazon places total emphasis on the world wide web and cloud computing whereas Wal-Mart places their major emphasis on “bricks and mortar.”

For the case of ii, Wal-Mart and Target are competitive rivals and both emphasize “bricks and mortar.” However, these two entities perform the same activities in different ways. Wal-Mart emphasize every day low pricing and Target emphasize shopping experience.

Finally, we have already seen that IBM has shifted away from producing from highly commoditized products (e.g. PC’s) towards providing innovation solutions to their clients consistent with their advertising theme of “making the world work better.” That is, they chose not to perform certain activities in their current business strategy.

The above examples, are designed to illustrate how the value chain lets you represent both the business model and the business strategy of a firm. For the case of the former all major value adding activities are required and identified. For the case of the latter the relative importance of the links must be identified. Once you are familiar with the firm at this level then you are able to interpret the results from financial statement analysis in a much more meaningful way.

But first, there are two other important dimensions to business strategy as indicated in Figure 1. These are formulating strategy and evaluating strategy.

Formulating Business Strategy and SWOT Analysis

A strategy cannot be formed in a vacuum, and its effectiveness will depend on various factors, both internal to the firm and external to the firm. One way to think about these factors goes by the acronym SWOT: “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats.” Remember that a financial statement only reflects what happened in the past and thus by the time a competitive threat facing a company actually starts affecting the financial statement, it may be too late.

For example, historically IBM was a major driver of the development and marketing of typewriters. In 1933 Thomas J. Watson, Sr. IBM’s founder and first president, purchased the production facilities, tools and patents of a small early producer of typewriters, a company named Electromatic. IBM was only 20-years old at the time and it put its development, production and marketing know-how into perfecting an electric typewriter. This ended up revolutionizing the typewriter industry.

Over time technology and the competitive rivalry changed and this resulted in IBM selling it’s typewriter division in 1990 to Lexmark whilst it still had some value. The importance of SWOT is to help management make strategic decisions even when they result in a major direction shift for the company. Just as Thomas J. Watson in 1933 made a bold strategic move based upon his assessment of future developments, under John Akers IBM made a significant strategic mode in eliminating this division in 1990. But then IBM was thrown into turmoil by the revolution that took place with PC’s and the back office linking PC’s in the early 1990’s. IBM suffered because it’s then strategy failed to emphasize customer relationships. This all changed with the arrival of Louis V. Gerstner Jr. as the first CEO hired from outside since Thomas J. Watson, Sr. Again this resulted in a major strategic shift for IBM. For the case of Gerstner he shifted IBM’s emphasis back to the customer resulting in large amounts of shareholder value being added to IBM.

IBM is not an isolated example. Another more recent example of external threats and strategic responses is the electronic book reader. Once these became widespread after Amazon popularized it’s Kindle, traditional booksellers could be out of business very quickly. This actually happened for the case of Borders whereas Barnes and Nobel was able adjust their strategy to embrace this new model.

SWOT analysis is designed to avoid this type of worst case scenario by identifying threats and reformulating strategy. The Internal Analysis that arises from SWOT usually result from traditional financial statement analysis. The External Analysis components of SWOT often result from Porter’s Five Forces Framework, described in the next topic.

What is SWOT Analysis?

• Internal Analysis

• S trengths: What are the firm’s comparative advantages over others in the industry?

– Best product, cool products (strong consumer ratings), 1 st mover advantage, strong balance sheet, strong innovation, strong CEO e.g. IBM’s L.V Gerstener Jr first CEO hired from outside of IBM since Thomas J. Watson Sr.

• W eaknesses: What are the firm’s comparative disadvantages relative to others.

– Is it too dependent upon a CEO when they stand down (e.g. KO’s Roberto C. Goizueta 1981-1997, Steve Job’s Apple), weak balance sheet, weak product lines (bad consumer ratings), little innovation

• External Analysis

• O pportunities: external opportunities for growth

– IPAD (Apple and Microsoft – the latter passed it over after developing it first)

• T hreats: external threats in the environment that can result in negative growth

– Smart Phones which has nearly knocked out Nokia, e-readers which did bring down Borders

• External Analysis often starts from Porter’s Five Forces Framework, described next.

External Analysis and Porter’s Five Forces Framework

This was first presented in 1979 in a Harvard Business Review article titled: “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy.” It identified the following forces as driving competition among firms in a given industry. These forces are:

Figure 5: Porter’s Five Forces

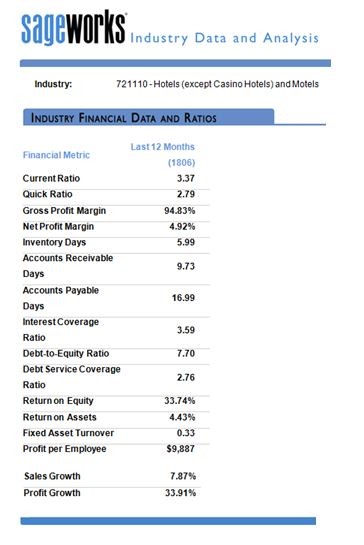

Together the first four forces determine the Competitive Rivalry within an Industry. Porter argued that collectively these five forces determine the ultimate profit potential of the industry and the essence of business strategy is dealing with competitive rivalry. This in turn means that these five forces plus the business strategy should be reflected in profitability measures for industries as reflected in aggregate financial statements. Valuation Tutor allows you to perform this type of analysis across sectors and industries for a wide ride range of profitability measures.

The above discussion has been aimed at developing your skills for identifying and understanding a firm’s business strategy. In the next section we introduce a tool that is used to communicate and evaluate a firm’s business strategy.

Business Strategy and the Balanced Scorecard Analysis

Another technique that is designed for both communicating and evaluating a firm’s business strategy is called the “balanced scorecard.” It takes a broader view and looks at both financial and non-financial measures. It looks at a company from four perspectives: financial (items like earnings), customer satisfaction, business process (which includes the activities performed by the firm), and “learning and growth” which tries to measure innovation (and therefore is a way to think about the future prospects of a company). The Balance Scorecard explicitly considers how the firm’s business strategy impacts upon these four perspectives.

Figure 6: The Balanced Scorecard

The balance scorecard represents business strategy in terms of four perspectives:

• “Financial ” perspective requires looking at measures that are relevant to the valuation of the company by shareholders.

• “Customer ” perspective requires the identification of performance metrics that measure the company’s success in meeting customers’ expectations viewed from the customer or outsider’s perspective

• “Process ” perspective refers to the internal activities performed by a firm – business efficiency

• “Learning and Growth ” perspectives refer to employee and informational activities requiring innovation and continual improvement.

Combined this allows for both the communication and evaluation of a business strategy at different levels of the organization and in this capacity is a popular topic in a management accounting course. Management accountants design a comprehensive set of performance measures (both financial and non-financial) to measure the impact of the business strategy upon the different parts of the organization.

From an analysts’ perspective this provides a useful framework for assessing the effects of a business strategy. This is because the effectiveness of a business strategy will eventually show up in the financial statements and supporting notes to the accounts.

For example, consider a firm that produces a great product but poor customer service. After some time, you would expect this to be reflected in sales. Similarly, a company that does not invest in learning and growth will eventually lose competitive advantage, and this will be reflected in its financial performance.

In our earlier example, for Coca Cola pre and post the acquisition analysts will be evaluating the impact upon three of the above four dimensions. First, the new strategy has placed more emphasis upon the Process dimension and evaluating the business efficiency of this dimension becomes important. In turn this allows more emphasis to be placed upon the customer because of the greater access to information and flexible scheduling at the regional level. This will be reflected in sales and marketing. Finally, at a combined level the overall effects of this investment decision will be reflected in the financial dimensions.

The above discussion makes clear that a full evaluation of a company cannot take place with just one year’s financial reports; how various ratios change over time is also important. In financial statement analysis, looking at performance across time is called “horizontal analysis.”

Step 3: Financial Statement Analysis

This leads us to the two main questions posed in the book:

• How do we measure how well they are performing in these tasks, i.e. how successful are they in implementing their business model?

• How much value are they creating, i.e. what is it worth?

These are answered in two ways: the first uses financial statement analysis, the second calculates an intrinsic value for a company using valuation models. An overview of valuation models is in the next section. In this section, we focus on financial statement analysis.

Let us start with measuring performance. One way is through financial statement analysis, which actually encompasses different methods, including ratio analysis, common size analysis, and activity analysis. Ratio analysis involves studying the financial reports of a company to understand its strengths and weaknesses. It lets you analyze a company’s performance along multiple dimensions. For example an important ratio in financial statement analysis is return on assets, or ROA, defined as profits divided by total assets. Total assets are defined as everything the company owns that can be used to produce income, and therefore measures the resources that are available to the company’s managers. ROA measures how productively the assets are being converted into profits. Ratios such as ROA also provide a basis for comparing companies.

There are many forms of ratio analysis. The origins of ratio analysis can be traced back to bank lending, which used such as the current ratio (which measures the company’s ability to pay back its short term debt). At the beginning of the 20th century, the DuPont model became a popular way to analyze performance; it consists of decomposing ROA into three sub ratios. Ratios are typically classified by what they are trying to measure. For example, liquidity ratios (such as the current ratio) measure the ability to pay back short term liabilities. Solvency ratios measure the ability to pay back long-term debt. Profitability ratios (such as ROA) measure how well the company creates profits from its operations. Activity analysis ratios (such as the inventory turnover ratio described below) measure how well the company is managing its resources.

A ratio such as ROA is a broad measure. You could also look more deeply into how the profit (also called the net income) is created from the total assets. One ratio that gives you deeper insight is called the degree of operating leverage, which measures how sales are converted into profits. Analysis of working capital provides more insight; it deals with short term operations. For example, you could look at the inventory turnover ratio, which tells you how quickly you are selling products. Other ratios give you insight into how it might perform in the future. For example, the current ratio tells you something about a company’s financial strength; it measures the ratio of current assets relative to its liabilities. If you have too many liabilities relative to your assets, your future prospects may not be as bright as those of other companies. Interestingly, this was one of the earliest ratios used by U.S. commercial banks in the 1890’s when they requested financial statements from companies wanting to borrow money (see Horrigan 1968).

In summary, ratio analysis provides you with a way of measuring performance and also provides a way to compare performance across firms. But the ratios cannot be interpreted in a vacuum; it is important to know the business model (what the company does) and the strategy (how it plans to do it). For example, consider a web design company and a retailer, who have very different business models. For the retailer, it makes sense to want a high inventory turnover; you do not want products sitting on a shelf or in a warehouse. But for the web design company, there is no real inventory that is being sold. So comparing these two very different companies along this dimension is not very useful.

Common Size and Activity Ratio Analysis

Financial statement analysis encompasses other techniques as well. These include Common Size Analysis and Activity Analysis. Vertical Common Size analysis re-expresses the major financial variables to make them comparable across companies by adjusting for size. For example, suppose company 1 has $1b in assets and another has $10m in assets. Simply looking at their earnings would not give you much information. But if you divide earnings (and all other variables, such as sales) by assets, you can get a more meaningful comparison of the companies. In fact, recent research has shown that investment divided by total assets can tell you a lot about stock returns and how stocks prices react to earnings announcements made by firms (Chan, Novy-Marx, and Zhang (2010) and Wu Zhang and Zhang (2009).

Horizontal Common Size analysis is similar, except that it adjusts for time by re-expressing the variables in terms of a base year. So current variables are then percentage changes from the base year, and this lets you see how fast different variables are growing. This is especially useful in evaluating the effects of a change in business strategy.

In any analysis of a company, business strategy matters. Consider a luxury retailer, who sells a few high price items during a year, and a discount retailer, who sells lots of inexpensive products. Both are retailers, but they have different business strategies. And we expect their ratios to reflect that: one should have a higher profit margin than the other. If the luxury retailer has low profit margins (profit divided by sales revenue) and low inventory turnover, it is not performing very well. We expect the discount retailer to have a low profit margin (after all, that’s what discount means!) but to make it up in volume, i.e. have a high inventory turnover.

So how do you know what to look for? This can be complicated. After all, the operations of a large multinational company can encompass many different activities. How do you think about the business model and strategy of such a company in a manageable way?

Over the years, different methods have been developed for broadly classifying models and strategies. These methods give you a framework for thinking about a company without having to work through every detail of the company’s operations. We cover some of these in Chapter 4, and give you a brief overview here.

Major Firm Decisions

Having decided on a strategy, a company carries it out by making different types of decisions. In the case of our bookstore, there are many such decisions. For example, should you focus on more expensive hard cover books (which generate more profits per book but sell fewer copies) or on paperbacks? How much should you spend on employee training so they can help customers? Should you advertise or rely on people walking by? How many discounts should you offer? Should profits be used to expand or be paid out to the owners? Should you borrow from a bank to finance operations or only use the owner’s capital?

These are all strategic decisions. Usually, they are separated into three categories:

· The investment decision: any decision that has to do with allocating resources. For example: whether to invest in a new computer system that can make tracking inventory and sales more efficient.

· The financing decision: how to pay for operations and expansion. For example: borrowing from a bank, issuing bonds, issuing shares.

· The dividend decision: how much of the profit to pay to shareholders

In Chapter 4, we will describe these decisions and their relationship to the business strategy of different companies. But we should mention that in recent years, more and more attention is being paid to another important decision: the risk management decision. Pretty much every business model entails some risk. These risks come from several factors, including general economic factors such as a slowdown or expansion of the economy, global events such as wars, financial factors such as changes in interest rates or exchange rates, and technological changes. But by thinking about the risks that matter most to your business, you can decide what risks you do not want to take. A simple example is using financial derivatives to hedge interest rate or exchange rate risk. A more complex example is to locate your manufacturing plants in different countries to diversify the risk of political upheavals.

The results of the decisions a company makes are reflected in their financial statements. In Chapter 3, we introduce tools used by analysts and management to analyze the performance of the firm’s investment decision. In Chapter 3, we study how the market “values” the firm’s investment decisions. This links the internal assessment to the external assessment; you could think you are doing well, but investors may not agree. Chapter 3 also introduces ratios that result from the firms financing and dividend decisions, and in Chapter 5, we again look at how the market views these results.

The primary ratio that reflects the investment decision is the Return on Assets (ROA), defined as the ratio of Net Income to Total Assets. This basically measures how much profit is being generated by the assets.

The financing decision is reflected in what is called the Financial Leverage Ratio (FLR). This is the ratio of Total Assets to Shareholders Equity. The latter measures the capital of the firm “owned” by the shareholders, formally defined as the difference between Total Assets and Total Liabilities. If the Financial Leverage Ratio is high, then a relatively small percentage of the assets are owned by the shareholders, and so the rest of the assets have been obtained by borrowing.

The product of ROA and the Financial Leverage Ratio is called the Return on Equity (ROE); it is the ratio of Net Income to Shareholder’s Equity, and therefore measures how much profit is being generated per unit of the capital of the firm that is owned by the shareholders.

The dividend decision is reflected in the Retention Ratio (RR), which is the percentage of earnings that is retained by the firm. One minus the Retention Ratio is called the Payout Ratio, and is the percentage of earnings that are paid out as dividends.

The three decisions come together in the definition of what is called Fundamental Growth (or Accounting Growth):

Fundamental Growth = ROE * RR

In Chapter 4, we will explain what this is in detail, but for now, note that it can be written as:

Fundamental Growth = ROA * FLR * RR

This quantity therefore reflects all three decisions.

In turn, each of these ratios can be decomposed further, providing more insight into the effectiveness of a firm’s strategy. These include Working Capital Ratios, Cash Management and Liquidity Ratios, Activity Analysis of Operations, Profitability Ratios, Solvency Ratios. The details of all these, and their interpretation in light of a company’s business strategy, are the focus of Chapter 4.

In summary, the financial statement analysis part of Valuation Tutor proceeds as follows. In Chapter 2, we show you how to get company filings from the SEC site, and explain the various financial statements. In Chapter 3, we develop the ratio analysis, complete with examples and a detailed explanation every calculation performed by Valuation Tutor. This reconciliation is critical to understanding some of the nuances that arise and some of the assumptions and judgments that have to be made in the analysis.

Chapter 4 focuses on the interpretation of results to help you understand how ratio analysis can be used to evaluate and compare firms. Finally, Chapter 5 extends the analysis to price based ratios. This chapter asks how the market view performance along the dimensions identified in Chapter 3. This is important for what is called relative valuation. The most popular price based ratio is the Price to Earnings (P/E) ratio, which measures how “valuable” the earning of a company are. But there are many other ratios as well, and you will see how to use them in Chapter 5.