The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Technical Analysis

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

The Efficient Market Hypothesis has been at the center of a debate in the world of finance since its articulation in the 1960s. Eugene Fama is widely credited with the hypothesis, although its early origins can be traced back to the French mathematician, Louis Bachalier. The hypothesis relies on Fama and Samuelsons work on the Random Walk Hypothesis which states that stock market prices evolve according to a random walk and thus stock market prices cannot be predicted.

The hypothesis has been at the heart of modern finance and concepts tied to it continue to be vital ingredients in widely used financial models including the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and the Black-Scholes model (widely used to price derivative instruments).

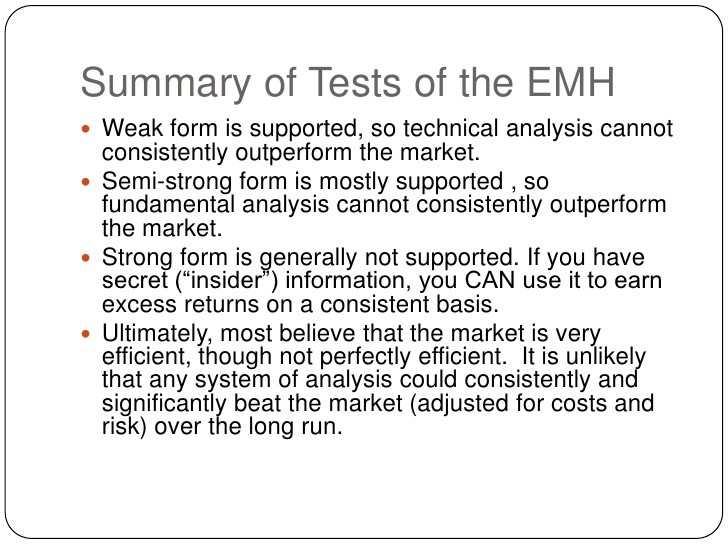

The Efficient Market Hypothesis most consequential claim is that prices reflect all available information. The implication of this assertion is that if current prices fully reflect all information, the market price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value and no investment strategy can be used to outperform the market.

Despite its widespread acceptance in modern finance, the hypothesis has faced continued criticism. The majority of early arguments were primarily technical in nature. They would focus on asymmetrical information and excess volatility as evidence of market inefficiency. Others pointed to theoretical flaws such as the lack of incentive provided to market participants to gather and act on new information if in fact all information was instantaneously absorbed into the price of a security.

However, the theory continued to gain traction. Several academic studies found evidence of Brownian motion in stock market prices, supporting a key premise of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Further studies focused on the role of market participants and Burton Malkiel provided tests that suggested a monkey throwing darts at a board with stock names on it was as likely to outperform the market as a wall street professional!

More fundamental criticisms of the Efficient Market and Random Walk Hypothesis have been articulated since the emergence of behavioral economics. Behavioral economists have displayed evidence of a laundry list of human biases, inconsistent with the premise of the efficient market hypothesis. Examples include a comfort in crowds or herding (Huberman and Regev, 2001), overconfidence based on little information (Barber and Odean, 2001), miscalibration of probabilities (Lictenstein, 1982) and evidence of regret (Clarke, 1994).

One of the greatest financial operators of our times offers more deep-rooted criticism that moves the debate on from correlation to causation. He points primarily to the difference between natural sciences and social sciences, to point to the instability of the equilibrium itself and the corresponding futility behind the ritualistic belief in market efficiency. In the crisis of global capitalism. George Soros wrote

Economic and social events, unlike the events that preoccupy physicists and chemists, involve thinking participants. And thinking participants can change the rules of economic and social systems by virtue of of their own ideas about these rules. The claims of economic theory to universal validity become untenable once this principle is properly understood.

While the book itself was aimed at broader implications of market failures on society, Soros makes further observations about markets that cannot afford to be ignored by academicians. For instance, he says that

Looking at currency markets, I discerned that prevalence of vicious and virtuous circles in which exchange rates and the so-called fundamentals that they were supposed to reflect are inter-connected in a self-reinforcing fashion, creating trends that sustain themselves for prolonged periods until they are eventually reversed.

Interestingly, Soros doesnt limit his observation of cycles to speculative financial markets alone, but extends his critique to essentially articulate the basis of the business cycle. He says

Studying the banking system and credit markets in general, I observed a reflexive connection between the act of lending and the value of the collateral that determines the crediworthiness of the borrower. This gives rise to an assymmetrical boom/bust pattern in which credit expansion and economic activity gather speed gradually and may come to an abrupt end.

What Soros articulated is the gap between financial theory as presented at universities across the world, and financial theory as market practitioners see it. Interestingly, Eugene Fama has himself acknowledged the inadequacy of the Efficient Market Hypothesis in a strict sense.

You have to tell me something about risk and something about expected returns, and then I can determine whether returns actually deviate from that. Market efficiency cannot be tested independent of some model of equilibrium. This makes these two concepts sort of inseparable twins.

The equilibrium in risk markets isnt a stable mechanism. Thats where technical analysis comes in. Infamously referred to as sharing a pedestal with alchemy by Burton Malkiel, Technical Analysis or the study of price (patterns, trends, cycles, waves, momentum) more closely represents a practitioners understanding of the economic world.

Participating in a competitive marketplace requires an outlook that is often at odds with theoretical economics. The implication isnt that practitioners need to reject economic theory, but they do develop parameters within which they can interpret a dynamic process. So, for instance, a technician may spend his time studying the flow of funds, measuring market sentiment, studying price momentum or arriving at answers on where we are in the business cycle.

The implications of rejecting the Efficient Market Hypothesis in the academic community would be fairly profound. Perhaps, it would even lead civilization to build robust systems that arent built on the assumption of human infallibility. Whats more consequential for market participants, however, is to recognize, as Henry Ford once said, you cant learn in school what the world is going to do next year.