The Dangers Of Deleveraging

Post on: 29 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

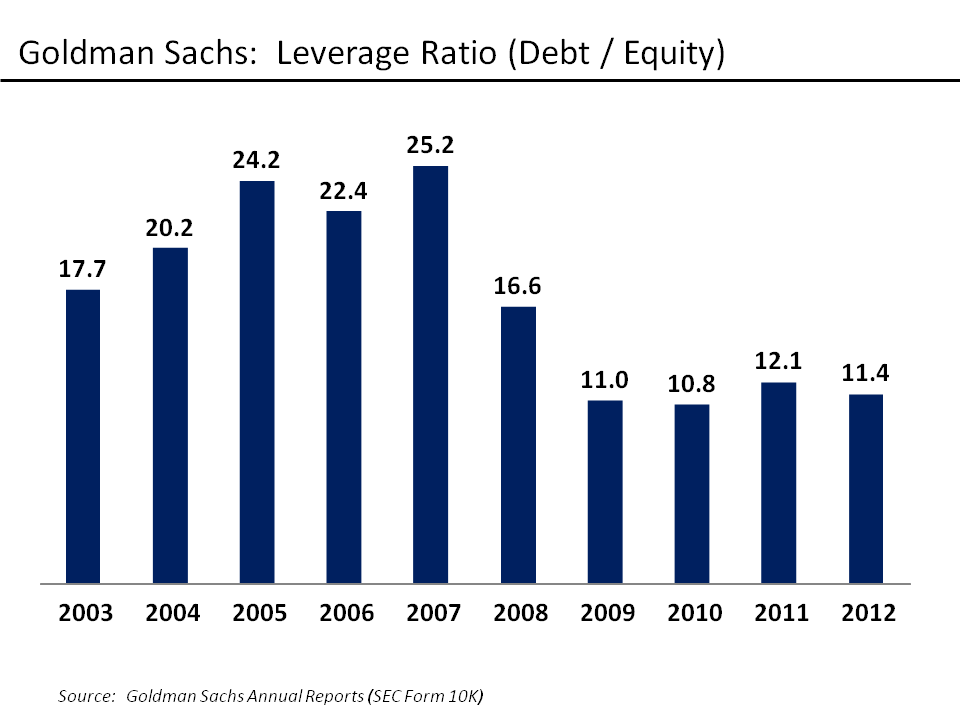

The U.S. economy is powered by consumer spending. This should come as no surprise, based on the number of ads you see playing on television, the plethora of malls dotting the country, or the deluge of credit card applications spilling out of the mailbox each week. Consumption as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has skyrocketed from a low of 49% in 1942, to a staggering 71% in 2010. Funding this feeding frenzy increased household debt as a percentage of disposable income to 128% in 2008, with middle income households adding the most debt. Business in the financial sector, especially broker dealers and real estate lenders, were also highly leveraged .

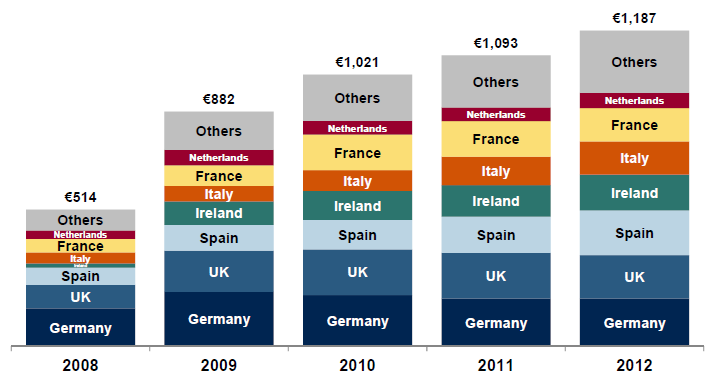

In 2008, the total debt to GDP ratio reached 469% in the United Kingdom and 459% in Japan. The U.S. household debt to income ratio doubled since 1980, with household debt increasing from $5,000 billion to over $10,000 billion. Much of this was the fault of real estate mortgages. with bank lending related to this sector of the economy ballooning to the equivalent of 73% of GDP, in the United States.

Global Credit

The explosion of the global credit bubble has many re-evaluating their spending habits, much to the chagrin of the world’s businesses. Many have blamed cheap credit for this predicament and now that consumers, businesses and governments alike have realized the follies of their youth, they have begun the painful process of deleveraging. Debt levels as a percentage of GDP in many rich world countries has leveled out, which on the face of things sounds good. The danger is that economic growth and deleveraging, while not a zero-sum game. are not the friendliest of bedfellows.

A recent report by McKinsey suggests that economic growth will continue to sputter during the beginning stages of deleveraging. Thirty two of the 45 instances of deleveraging since the Great Depression. have followed a financial crisis and half of these instances involved the sort of austerity measures being proposed today. The deleveraging process typically starts two to three years after the beginning of the recession and lasts an average of six to seven years. During the initial period of deleveraging, real GDP growth falls by an average of 0.6%. Even after real GDP growth begins to increase, the process of deleveraging continues. This growth is often kick-started by an increase in exports, which helps counteract an increase in savings rates from businesses and households shedding debt. Unfortunately, indicators point to this global recession being different, for a couple of reasons.

First, banks are not lending out the money flowing into their coffers from households paying down their debt. This may be because banks are still writing down mortgage debt, or because they want to keep more cash on hand to deal with mortgage-related lawsuits. The low interest rate environment would suggest that both households and businesses with low debt ratios would be willing to add debt to their balance sheets. but borrowing has simply not rebounded. (To know more about deleveraging, read: Deleveraging: What It Means To Corporate America .)

In Need of Government Cash

Second, governments are entering into austerity measures at a time in which government cash is what the economy may need. Previous recessions, especially difficult ones, were marked by an increase in government spending. Think of the public works projects of the Great Depression. Today, governments face the dual prospect of cutting debt and increasing spending, a seemingly impossible task, politically. Eurozone pressures on Greece to cut public spending may very well lead to its default on debt, and political resistance to spending increases in America, even on infrastructure, may be depressing economic growth.

Third, the global nature of this recession prevents the sort of export-driven recovery that has occurred in the past. In previous recessions, governments were able to counter an increase in saving and drop in consumption with higher net exports. This works when a few countries are experiencing economic problems, but is nearly impossible when a recession is on a global scale. For a country to increase its exports, another country must increase its imports. However, if consumers have cut spending, there may not be the levels of demand necessary to call for greater export supply, let alone problems with obtaining credit. (For additional reading, check out: Why Today’s Recession Tops The Great Depression .)

The Bottom Line

The danger of deleveraging is exacerbated by the wide range of economic policies floating around in the wake of the financial crisis, many of which may torpedo recovery. Policy makers may fall victim to the idea of treating the symptoms, rather than the disease by focusing on short-term solutions. Overcoming this would require an examination of the sort of incentives that prompted households and businesses to take on so much debt in the first place, whether tax incentives, such as mortgage credits, or low interest rates.

Financial institutions should treat their debt portfolio as any other investor would, by ensuring diversification across both risk and sector. In the short-run, adopting these policies may exacerbate the problem, just as it’s hard to ride a bike the first time you climb on. Business leaders will have to get used to a different lending and development environment, one in which credit is dearer and regulatory requirements higher. Government leaders will have to overcome party-line biases to achieve change, especially change that won’t help them in the next round of elections.