New Roth 401(k) Plans Target HighIncome Earners

Post on: 31 Март, 2015 No Comment

Jane J. Kim Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Updated March 30, 2005 12:01 a.m. ET

Individuals who make too much money to contribute to a Roth individual retirement account may get a new opportunity to do so next year.

Earlier this month the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service released proposed regulations that provide guidance on how employers can add Roth 401(k) accounts, created as part of the 2001 tax law, to their plans starting January 2006. The new accounts will combine features of traditional Roth IRAs with those of 401(k)s.

As with Roth IRAs, individuals pay income taxes on contributions upfront but can withdraw those contributions and earnings tax-free after age 59, provided they have held the account for at least five years. In contrast, contributions to a 401(k) are made with pretax dollars, which immediately reduces their taxable income, and withdrawals are later taxed as ordinary income.

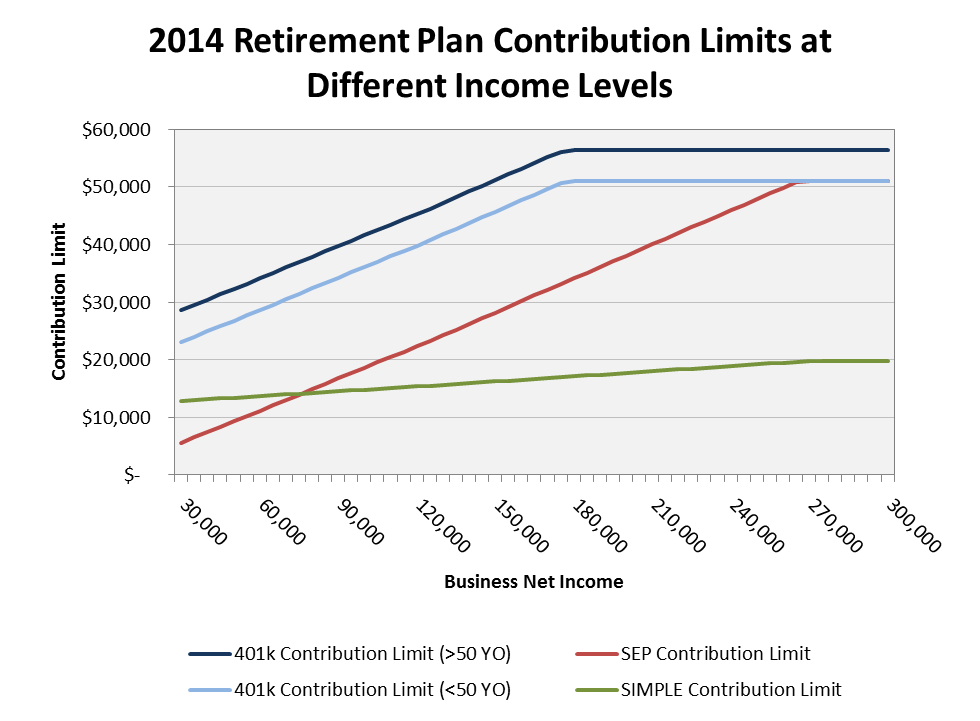

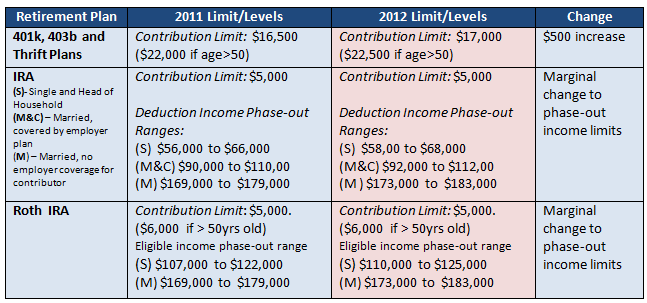

The accounts should be a boon to individuals who can’t contribute to a Roth IRA because their income is too high and for those who want to save more in those accounts than what they are currently allowed. Making contributions to a Roth account through payroll deductions, for one, will allow workers to sock away as much as they would to a regular 401(k), which is $15,000 (or up to $20,000 for those age 50 and older) next year. With a traditional Roth IRA, the maximum contribution next year is $4,000 (or $5,000 for those who are 50 or older). Most important, there will be no income restrictions on who can contribute to the new plan. With regular Roth IRAs, married couples who have more than $160,000 in modified adjusted gross income (more than $110,000 for singles) can’t contribute.

But workers may have only a limited window to make contributions, because the opportunity to open or contribute to the new accounts, like most provisions created as part of the 2001 tax act, will expire after 2010, unless Congress extends those provisions. If the rules expire, then money in a Roth 401(k) at the time will be allowed to stay in the plans or be rolled over into a regular Roth IRA, although workers won’t be able to make new contributions.

While the Roth 401(k) plans will provide more flexibility, they could add another layer of complexity for workers who have to decide how to split their contributions between their regular 401(k) and Roth 401(k). Any contributions made to either account will count toward the maximum 401(k) limits next year. And if an employer provides a matching contribution, the match is made on a pretax basis and will be put into a separate account, such as their 401(k) or profit-sharing account — even if the worker directs all of his or her contributions into a Roth 401(k) account. Workers, though, would have to pay income tax on the employer contribution when they withdraw it.

For most employees, the decision will boil down to deciding whether to take the tax break on the front end with a 401(k) contribution or on the back end, through a Roth 401(k) — a decision that will depend largely on how long you have to invest and what your tax rates are when you put the money in and when you take it out.

Most experts say younger workers would benefit with a Roth 401(k) since, presumably, their income will increase as their career progresses, while those in their peak earnings years could be better off making pretax contributions if they expect to be in a lower tax bracket when they pull the money out in retirement.

One potential drawback: Roth 401(k)s are subject to minimum-distribution rules, so individuals will be required to take minimum distributions after age 70 unless they roll over money in the plans into regular Roth IRAs. If they roll over to a regular Roth IRA, they won’t have to worry about taking distributions during their lifetime and can pass on the assets to their heirs for years of tax-free growth, says Ed Slott, a Rockville Centre, N.Y. accountant who specializes in IRAs.

Meanwhile, new rules that take effect this week will benefit workers who have accumulated less than $5,000 in their 401(k) plans before moving onto a new job. Previously, if the employee didn’t roll over such an account to their new employer’s plan or to an IRA, the employer would often cash them out of the plan — leaving the employee open to taxes and penalties. Now, employers have to automatically roll over accounts between $5,000 and $1,000 into an IRA, so that workers can continue to save on a tax-deferred basis.