NAIC Capital Markets Special Report

Post on: 11 Октябрь, 2015 No Comment

Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities and the To-Be-Announced (TBA) Market

While the residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) market is well known and the NAIC Capital Markets Bureau has written at length about this market previously what is less well known is that a vast majority of trading in agency RMBS securities is done in the to-be-announced (TBA) market. According to Securities Industry Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) data, out of approximately $60.1 trillion in agency RMBS trading volume reported to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authoritys (FINRA) Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) system during the first 10 months of 2012, an astounding $56.7 trillion (or about 94%) was done in the TBA market, with daily trading volumes averaging $271 billion year-to-date (through Oct. 31, 2012). Figure 1 below shows the average daily trading volumes of agency mortgage-related securities since 2004. Notably, the TBA data shows up as a category only since 2011, when it became tracked by TRACE; however, based on anecdotal evidence, we would expect the 20042010 period to show a similar share of TBAs out of the total agency mortgage-related trading as displayed in 2011 and 2012.

This special report describes the TBA market, its mechanics and its importance to the agency RMBS market; examines the insurance industrys reported exposure to the TBA market; and discusses the financial statement reporting of TBA transactions by U.S. insurers. In addition, we discuss the investment rationale and risks of the TBA market for insurers, and lastly, touch upon the potential impact on the TBA market from the impending U.S. mortgage finance reform on the back of the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corps (Freddie Mac) government conservatorship.

TBA Market Description, Mechanics and Liquidity

According to SIFMA, the TBA market was established in the 1970s with the creation of pass-through securities at the Government National Mortgage Association (or Ginnie Mae) to facilitate the trading of RMBS issued by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs or Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and Ginnie Mae together, the Agencies. In 1981, SIFMAs predecessor, the Public Securities Association (PSA), published the Uniform Practices for the Clearance and Settlement of Mortgage-Backed Securities and Other Related Securities, eight chapters of which lay out so-called Good-Delivery Guidelines generally adhered to by TBA market participants. These guidelines cover a number of areas surrounding TBA trading and are endorsed and maintained by SIFMA; their purpose is to standardize various settlement-related aspects of TBAs in order to enhance and maintain the liquidity of the TBA market.

Notably, only agency-issued and/or agency-guaranteed RMBS are TBA-eligible; additionally, only single-class (no multi-class, like collateralized mortgage obligations, or CMOs), pass-through (without tranching or structuring of cash flows) securities are eligible to trade in the TBA market. Furthermore, only conforming mortgages which meet a certain size and credit quality criteria can be guaranteed by the agencies. These very specific requirements result in the standardization, and, therefore, the liquidity, of the TBA market.

In a TBA trade, two parties usually an investor or market maker and a loan originator agree on a price for delivering a certain amount of agency RMBS at a specific future date. A distinguishing characteristic of a TBA trade is that, at the start of the transaction, the actual identity of the RMBS securities to be delivered at settlement is not stipulated. Instead, the two parties agree on six parameters of the TBA trade: issuer, coupon, maturity, price, face value (or par amount) and the settlement date.

For example, an investor agrees to buy $100 million of Freddie Mac 15-year securities with a 5% coupon at a given price for delivery in two weeks from the counterparty. The key dates are the trade date, the notification date (commonly called the 48-hour day) and the settlement date. A timeline for a typical TBA trade is depicted in Figure 2 below.

According to industry practice set forth in SIFMAs Uniform Practices Manual, the seller will inform the buyer of the identity of the securities in the RMBS pool no later than 3 p.m. two business days (the notification date) before the pool is scheduled to be delivered (the settlement date). TBA trades are generally settled within three months, with the nearest two months being the most liquid, due in large part to TBAs use in dollar rolls discussed further in report. To streamline the process, SIFMA selected a single settlement date each month for each of the several types of agency MBS (e.g. 15-year, 20-year and 30-year maturities with three or four sets of prevailing coupons). Therefore, depending on when the next monthly settlement is, the trade date will usually precede the settlement date by two to 60 days.

Figure 2: Typical TBA Trade Timeline

Similar to Treasury futures, TBAs trade on a cheapest to deliver basis, which means that the seller (usually a loan originator or a broker) has a strong incentive to select securities of the lowest value and quality (like those with a higher prepayment risk based on their size, loan-to-value (LTV) and geographical characteristics (which are not specified in the original trade terms) that satisfy the trade terms that were specified on the trade date. What is remarkable about the TBA market is that, while this adverse selection is generally anticipated by the buyer and has the potential to lower the price of the security, the liquidity benefit of trading standardized, homogenous pools of MBS mitigates the cheapest to deliver discount by raising the pools price relative to what it could achieve in a less liquid market. The homogeneity assumption is a cornerstone of TBA trading, helping to transform an essentially heterogeneous set of individual underlying mortgages into a large set of fungible (i.e. easily substitutable) MBS pools and driving the TBA markets liquidity.

TBA Markets Importance for the RMBS Market and Mortgage Lending in General

This liquidity and ease of mortgage risk management by transferring said risk from one market player to another is what makes the TBA market so important and prevalent in the overall MBS market, ultimately resulting in lower mortgage rates. To that point, because mortgages in a TBA trade do not have to be identified until the notification date, they might not even exist at the trade date. The nature of a TBA transaction allows lenders and loan originators to lock in rates in the TBA market and then go to the borrowers and offer them competitively priced rates, knowing that they already have a buyer for a subsequent MBS pool. Therefore, the TBA market is critical for lenders, as it enables them to hedge their own interest rate risk when they offer potential mortgage applicants an option to lock in a mortgage rate for anywhere between 30 and 90 days. Although lenders can use other instruments to hedge this particular interest rate risk exposure, the TBA market offers the most efficient hedge for their mortgage-origination efforts.

Additionally, the explicit (for Ginnie Mae) or implicit (for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac ) government guarantee of agency RMBS provides further reinforcement for the TBA markets liquidity, by removing credit risk out of the equation and leaving the participants focus on the underlying mortgage characteristics and prepayment risks. The potential removal of this guarantee resulting from GSE reform would have a negative impact on the viability of the TBA market, according to reports issued by SIFMA and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which we discuss in greater detail in a later section of this report.

Specified Pool Trading and Dollar Rolls Long-term vs. Short-term Investment

A discussion of the TBA market would not be complete without a mention of specified pool trading and dollar rolls. Specified pool trading refers to agency RMBS trading outside the TBA market, where investors specify securities to be delivered into the pool, making it a substantially less liquid market. Although most RMBS securities trading this way are normally not TBA-eligible (such as jumbo loans and/or those with lower credit quality), some are certainly chosen by investors for their more attractive prepayment characteristics (based on their size, LTV and geography) that help to avoid the cheapest-to-deliver adverse selection problem. Therefore, investors (including insurance companies) looking to invest into RMBS on a longer-term basis generally do so via the specified pool route, using the TBA market largely to achieve a different strategy such as short-term income generation via dollar rolls.

A dollar roll is a transaction similar to a repurchase transaction (repo), where a TBA security with a near or front month settlement is bought or sold at a specified price and an offsetting trade for a future or back settlement month is executed at a lower price (this price difference between months is called the drop). Typically, an investor owning a TBA with a front month settlement will sell it to a broker/dealer looking to cover an existing short position (which can result from a mortgage supply/demand imbalance when interest rates change) and will agree to buy a substantially the same (as opposed to exactly the same, as in traditional repo trades) TBA pool with a back month settlement at a future date. By selling the front month TBA, the investor foregoes the delivery of the securities and operational issues that come with it, foregoes any coupons and prepayments that the TBA would generate in the interim, but has funds that can be reinvested in the short-term based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). This short-term interest and the price drop of the back month TBA repurchase are the sources of income generation in the dollar roll trading for investors, and many investors actively roll from one month into another, enjoying the benefit of the TBA market liquidity and exposure to MBS without the adverse consequences of receiving delivery of a less-than-desirable mortgage pool.

Investment Rationale and Risks of TBAs

Given the market dynamics described above, we believe that a majority of the TBA securities identified among insurers year-end asset holdings and intra-year transactions are a result of these short-term income-generation dollar roll transactions (as further witnessed by their short holding periods), as opposed to a way to invest long-term into upcoming MBS pools. Additionally, some insurers may use TBA securities to hedge interest rate risk exposure arising from other rate-sensitive securities they may be holding.

The risks of TBA investing are similar to those resulting from other mortgage-related investments, including interest rate and prepayment risks. Given the tremendous liquidity in the TBA market, counterparty risk is generally not an issue, although during distressed times it could become one, especially for dollar rolls where a counterparty relationship is of greater importance due to the repo nature of the transaction.

Statutory Accounting for and Financial Statement Reporting of TBAs

SSAP No. 21Other Admitted Assets provides some accounting guidance for TBAs in the Receivables for Securities section, paragraphs 7 and 10. Paragraph 10 specifically states that receivables arising from the secondary sale of securities acquired on a TBA basismay be admitted until the security is exchanged for payment. SSAP No. 21 also goes on to say that [p]rofits or losses emanating from the secondary sale transaction are recorded in the same manner as profits and losses emanating from any other sale transaction involving an investment.

According to the Investment Schedules General Instructions of the 2011 NAIC Annual Statement Instructions. To Be Announced securities (commonly referred to as TBAs) are to be reported in Schedule D unless the structure of the security more closely resembles a derivative, as defined within SSAP 86 Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities. in which case the security should be reported on Schedule DB. The exact placement of TBAs in the investment schedules depends upon how a company uses TBA. This language might be somewhat misleading because, as mentioned earlier, TBAs are technically not derivatives but, rather, forward commitments. However, if TBAs are used for hedging purposes, they should be reported in Schedule DB. In addition, TBAs generally do not have varying structures.

Additionally, Schedule D, Part 1 (Long-term Bonds Owned December 31 of Current Year) instructs reporting companies to enter a code (&) in Column 3 to easily identify TBAs. In our analysis, we noticed that, while some companies have included the & sign for their TBA holdings, others have relied on the Description field alone, making it more difficult to track such holdings. Moreover, other parts of Schedule D (Part 3 through Part 5) do not even provide a Code field, leaving the Description field as the only place to note a particular holding or transaction as a TBA. Similarly, Schedule DB does not offer a separate field to identify TBAs, leaving also only the Description field for that task. Lastly, we noted in our analysis that there were wide variances in how the Description field was filled out for TBAs. Given this variability of terminology or lack of proper identification altogether, we believe that our totals in the analysis above are less than the actual amounts, albeit most likely not by a significant measure.

Insurance Industry Exposure to TBAs

In our effort to assess the insurance industrys exposure to the TBA market, we found that insurers have been reporting their holdings of TBAs both on Schedule D (Long-term Bonds and Stocks) and Schedule DB (Derivative Instruments). Although, technically, TBAs are not derivatives despite their forward commitment, some insurers may have classified them as such because these securities may have been used for hedging certain interest rate exposures.

Given the fairly short-term nature of most TBA contracts, only a small portion of the insurers activity in the product has been captured by the year-end holdings on Schedule D, Part 1, Long-term Bonds (based on book/adjusted carrying value, or BACV) and Schedule DB, Part A, Section 1, Derivatives (based on notional values). Therefore, we reviewed the intra-year trading activity as captured by Schedule D, Part 5, Long-Term Bonds and Stocks, and Schedule DB, Part A, Section 2, Derivatives (in the latter, we deducted the prior year-end holdings to avoid double-counting), which revealed much broader insurer participation.

Based solely on the year-end holdings, insurers across all five industry groups held about $9.3 billion of TBAs at the end of 2011 (or about 0.18% of total year-end Cash and Invested Assets of $5.23 trillion) and $7.9 billion at the end of 2010 (or about 0.15% of total year-end Cash and Invested Assets of $5.02 trillion). When we combined the year-end TBA holdings with the intra-year activity volumes in Table 1, insurers have owned and/or traded about $106.7 billion in TBA securities in 2011 (or about 2.0% of total year-end Cash and Invested Assets of $5.23 trillion) and about $96.6 billion in TBA securities in 2010 (or about 1.9% of total year-end Cash and Invested Assets of $5.02 trillion). Although these amounts are fairly small relative to insurers asset base, they do show a relatively robust participation by the insurers in the TBA market.

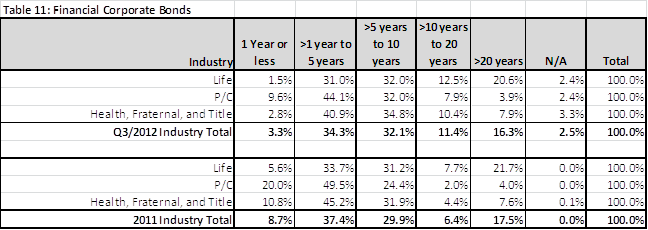

In terms of specific industry groups. life companies have been responsible for about 78.5% of overall TBA activity in 2011 and about 76.4% in 2010. They reported a majority of that activity (about 60% in 2011 and about 55% in 2010) on Schedule DB (Derivatives), indicating interest rate hedging as the purpose for the trade. Fraternal insurance companies were a distant second in TBA trading activity, contributing 14.1% in 2011 and 14.6% in 2010, and reporting all of that activity on Schedule D (Long-Term Bonds). Property/casualty companies added 4.7% and 6.0% to the TBA activity in 2011 and 2010, respectively; health companies, 2.7% and 3.1%, respectively; and title companies, 0.0% in both years. To determine insurer concentration within specific industry groups for TBA activity, we looked at the 2011 Schedule D, Part 1: the life industry was represented by 28 individual reporting entities; fraternal by only one, property/casualty by 80; health by 49; and title by two. Therefore, the fraternal industry exhibited the highest insurer concentration, even after taking other factors into account, with most transactions indicative of TBA usage for dollar rolls and a likely investment strategy of income generation. Additionally, the fraternal industry displayed a disproportionately larger participation in TBA activity as a percentage of their overall asset base and transaction volume (15%) both in 2010 and 2011 about six times more than the health industry (2.5% in 2011 and 2.9% in 2010).

Table 1: Total TBA Activity, Year-end Holdings Plus Intra-year Transactions (as Reported in Schedule D, Long-term Bonds and Stocks, and Schedule DB, Derivatives)

To understand the insurance industrys involvement with the TBA market historically, we reviewed TBA activity from Schedule D, Part 5 (intra-year Long-term Bond trading transactions) for 10 full years between 2002 and 2011. (We selected only one out of the four schedules reviewed in the analysis above in the interest of minimizing time and complexity, while still capturing a historical trend.) We found that the insurance industrys activity in the TBA market in the past five to six years (20062011) has been relatively muted, compared to the earlier years of 20022005 (Table 2), with the peak activity of $252 billion occurring in 2003. Although that 10-year peak activity was almost five times larger than in the past couple of years, it appears less striking when we overlay our insurer TBA activity data with the agency MBS issuance numbers (Figure 3). In the history of the product, 2003 had a record MBS issuance of $2.1 trillion, with only 2009 coming somewhat close ($1.7 trillion).

In this context, the peak TBA activity by insurers in 2003 is, therefore, much less surprising than the fact that TBA activity has not been higher in recent years, especially in 2009 when the second-highest amount of MBS was issued between 2002 and 2011. The most obvious explanation for the decline in TBA activity is that, subsequent to the 2008 financial crisis, the majority of companies with sizable investments in mortgage-related securities have scaled back their exposure to them, having suffered serious losses during the crisis and having found a new sense of risk aversion (or at least caution) toward mortgage-related products. Although mortgages underlying TBAs carry an explicit or implicit government agency guarantee, the perceived risk of any mortgage-related asset among investors has been noticeably higher since 2008. Additionally, the conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac has not helped in building confidence in their MBS guarantees.

Lastly, another potential factor contributing to the lower TBA activity reported on Schedule D (Long-term Bonds) and its various parts could be a shift by some insurers toward reporting such activity on Schedule DB (Derivatives) instead, as that schedule has become more detailed and transparent in the recent years. However, we have not performed extensive analysis of that conjecture at this time. Still, as the totals of Schedules D and DB show in Table 1 above, the overall captured TBA activity in the past two years was still less than half of the 2003 TBA activity reported on Schedule D, Part 5 alone. Therefore, were we to aggregate the Schedule D and DB numbers for the past 10 years, they would still show a downward trend in insurer TBA activity, although likely with a less steep slope.

Finally, as the last column in Table 2 shows, between 2002 and 2004, TBA trading had a much higher share of insurers intra-year trading activity reported on Schedule D1, Part 5, ranging between 20% and 28%; in the most recent five to six years, that share has decreased to an average of about 12%, as insurers have reduced their overall participation in the TBA market.

Table 2: TBA Activity History from Schedule D, Part 5, Long-Term Bonds and Stocks

Figure 3: TBA Activity History and Agency MBS Issuance (2002-2011)

Agency Reform and Its Impact on the TBA Market and the Insurance Industry

The Agencies have historically played a vital role in the U.S. mortgage finance market, purchasing loans, securitizing them into MBS securities and guaranteeing (either explicitly or implicitly) the receipt of interest and principal on those securities. The key benefits of the Agencies involvement in the MBS market are the standardization of mortgage loan origination, the credit guarantee and the Agencies exemption from the registration requirements (sales of newly issued MBS via the TBA market would not be possible without such an exemption). The Agencies serve as a cornerstone for the proper functioning of the TBA market and its resultant size and liquidity.

However, the Agencies, particularly Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are currently under intense scrutiny and reexamination, following their near default after the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent governmental conservatorship. The U.S. Treasury Department and Congress are in the process of considering and evaluating different options for reforming the GSEs, ranging from full privatization to full nationalization, with several other options in between. The potential removal of the Agency guarantee, or, even worse, of their overall gargantuan participation, would likely have a significantly detrimental effect on the TBA market and its liquidity, ultimately trickling down to individual borrowers in the form of higher mortgage rates. Both SIFMA and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York have expressed their foremost concern over the viability of the TBA market as a result of the housing finance reform, and they have argued that whatever solution is eventually arrived at, it should include the TBA market in some shape or form.

Although the insurance industrys direct exposure to the TBA market is limited, broader repercussions of GSE reform for all mortgage-related securities are of a greater importance because they have been an important investment vehicle for insurance companies. The Capital Markets Bureau will continue to monitor trends surrounding the TBA market and the impact on insurance industry investments. We will report on any developments as deemed appropriate.