Mutual fund turnover and taxes

Post on: 11 Июль, 2015 No Comment

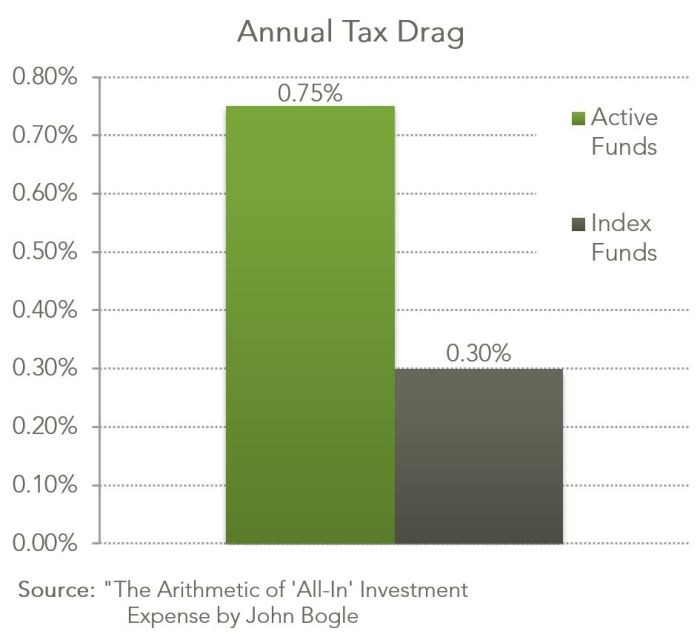

When a mutual fund portfolio manager sells shares within the fund, it can trigger a capital gains distribution — that means a tax bill for you. For the most part, it’s a good idea to steer clear of funds that rack up big tax bills while you hold the shares.

The Securities and Exchange Commission says more than 2.5 percent of the average stock fund’s total return is lost each year to taxes, significantly more than the amount lost to fees. The tax bite varies from zero percent for the most tax-efficient funds to 5.6 percent for the least efficient.

The turnover ratio is the best indicator of how much buying and selling goes on within a fund.

William Harding, an analyst with Morningstar, says the average turnover ratio for managed domestic stock funds is 130 percent.

Many managers claim to be long-term investors when, in reality, the average mutual fund manager is turning the portfolio more than once a year.

It’s not always the case that lower turnover always means greater tax efficiency, says Harding. But, generally, really low turnover leads to greater tax efficiency because it means management isn’t selling stock as often, so the portfolio isn’t realizing capital gains.

Turnover ratio is best when comparing two funds in the same category — growth, value, and the like; but turnover by itself doesn’t always tell the whole story.

The average growth fund probably has 25 percent more turnover than the average value fund, yet value funds can be less tax-efficient. A growth manager buys and holds the winners and sells the losers. A value manager buys something at a discount to its intrinsic value and has a strict sell discipline, says analyst Fran Kinniry at Vanguard.

At times, trading can be a means to greater tax efficiency. A manager may be selling losers to offset gains in the portfolio.

The telling turnover ratio

The National Association of Investors Corporation, based in Madison Heights, Mich. considers turnover a key number when evaluating mutual funds — even if the fund will be held in a tax-deferred retirement portfolio.

We look for a turnover ratio of 20 percent or less, says Dennis Genord, manager of NAIC’s mutual fund education program. We’re from a long-term perspective. You need to get a grip on what’s being invested in the fund. If that fund has a 100 percent turnover ratio, you can’t get a feeling for what the fund invests in.

Another consequence of heavy trading by a fund manager is that every trade results in transaction costs that get passed on to shareholders, Genord points out.

Sometimes the manager has little choice but to sell. When the market tanks and investors sell their shares, managers may have to sell stock if there’s not enough cash on hand to meet shareholder redemptions.

The flip side of trading too much is that trading too little may mean there are large capital gains that will result in an extra big tax when the shares within the fund are eventually sold.

Suffering from exposure?

Investors who buy into a fund shortly before a distribution is made (called buying a distribution) can get hit with a capital gains tax when their shares haven’t had time to appreciate. This is always a nasty surprise, especially so if the gains have really built up.

Morningstar’s Harding says that’s why it’s important to know the capital gains exposure of a fund.

Morningstar always publishes this. It’s the total unrealized gains of a fund and could be a clue to the potential capital gains exposure. It’s calculated as a percentage of net assets. If the management team has a low turnover approach, it may not be a big concern. The other thing is the shares they’re selling are probably long-term gains that are taxed at a lower rate.

A key to not buying a distribution, is to check the fund’s distribution schedule before purchasing shares. That information is in the prospectus and may also be on the fund family’s Web site.

The SEC wants investors to see the impact taxes have on returns generated by the funds. It now requires that mutual fund families be upfront about the effect taxes have on each fund. After-tax returns must be presented in two ways in the prospectus and in any advertising that makes claims about the tax efficiency of the fund.

The first number is the return after taxes on distributions. It’s the tax effect of the manager’s trading of shares within the fund.

The second number, the return after taxes on distributions and the sale of fund shares, is the effect of both the manager’s trading within the fund and the taxable gain or loss realized by shareholders for selling shares.

The numbers are meant to show a worst-case scenario, so the taxes are computed at the maximum federal income tax rate. The after-tax return for both cases must be stated for one-, five-, and 10-year periods.