MarkToMarket Mayhem

Post on: 27 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

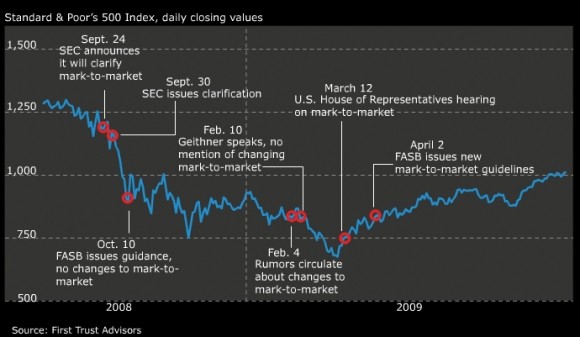

When Washington Mutual Bank (OTC:WAMUQ ) failed in September 2008, it was the largest bank failure in American financial history. At the time, the question on many people’s minds was, How can a corporation go from billions of dollars’ worth of assets on their balance sheets to zilch overnight? There are many factors that contribute to a bank’s failure, but part of the answer to why many banks were brought to their knees in 2008 is mark-to-market accounting (MTM), in which a security’s value is recorded in a company’s books at its current market value, rather than its book value. As you might imagine, this method can have serious repercussions in a bear market, leading to much larger losses than traditional accounting. As it turned out, it had even more serious repercussions when applied to new, thinly traded mortgage securities, an effect that contributed to the credit crisis of 2008 and the bank failures that ensued.

Mark to Market

In the accounting world, the numbers on a company’s books are rarely indicative of market values. According to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), companies are supposed to record the value of assets at their cost in order to err on the side of caution. In other words, if a bakery buys an oven for $10,000, the purchase is recorded as an asset on the company’s balance sheet for $10,000 — even if it could be sold for more in the marketplace.

This system has worked pretty well because it ensures that everything is valued on an even playing field. While assets may not equal fair value, at least Company X’s assets are the same as Company Y’s.

This all changed in the 1980s when companies started to adopt mark-to-market accounting. Just as the name implies, with mark-to-market accounting, certain assets are recorded at their fair market values. not at cost, as was previously the norm. One of the biggest spurs for the change was the new way America did business; investing had become increasingly popular and accessible, and businesses had started thinking that padding their coffers with stocks and bonds was a lot more lucrative than hoarding cash.

It didn’t make sense, they argued, to keep recording liquid assets like stocks and derivatives at their cost when investors wanted to learn the true value of what was on the books. The accountants capitulated — after all, the point was more transparency for investors. (To learn more, read Show and Tell: The Importance Of Transparency .)

Keeping Conservative or Marking to Nothing

Despite its benefits, not everyone is a fan of marking assets to market value. Detractors say that mark-to-market accounting is dangerous because it allows companies to use hypothetical numbers to account for hard-to-value financial instruments (like collateralized debt obligations ). And indeed, with certain types of securities (like level-3 assets ) discretion plays a big part in what you see on a company’s books.

In October 2008, in response to the effects mark-to-market accounting had on the subprime crisis. the SEC began a study on MTM, and the Financial Accounting Standards Board proposed FAS 157-d. an accounting rule that would regulate the use of mark-to-market accounting on assets with no active market. (For related reading, see Policing The Securities Market: An Overview of the SEC .)

Using market value hasn’t always been such a hot topic in the financial world. In fact, at one time it was considered the conservative choice. Before MTM, there was lower cost or market accounting (LCM), a rule in which companies had to mark their assets down to cost or market, whichever was lower.

LCM ensures that assets that have lost value since they were purchased aren’t artificially inflated on the books.

In WaMu’s case, the use of mark-to-market accounting lead to volatility for the company’s shareholders. That’s because the fair value of its subprime mortgages became increasingly difficult to calculate when the mortgage market began to dry up in 2007. As financial institutions clung to the high valuations to which they were accustomed, the bottom fell out of the subprime arena, and companies with billions of dollars of subprime on their books were forced to write those assets down to almost nothing. For investors, this meant that a company’s assets could be wiped out overnight — and share prices reflected this. (For more information on the subprime meltdown, read The Fuel That Fed The Subprime Meltdown .)

Know What You Own

Using MTM isn’t discretionary — companies can’t just decide that they’d rather use it to value assets like stocks or inventory. Derivatives are assets in which marking to market is the general guideline because, like stock options, derivatives have finite lives and tend to fluctuate in value.

Stocks are a different story. GAAP rules dictate that stocks can only be marked to market if the company doesn’t plan on holding onto the securities for a long period of time. Most of the time, stocks are recorded at cost. Assets like inventory are also recorded at cost, not their fair values; one situation where this changes is when derivatives are used to hedge against inventory price changes. In this case, inventory can also be marked to market.

But just because all of these assets can be recorded at fair value on the books doesn’t necessarily mean that investors have something to worry about.

When it comes to fairly valued assets, stocks and bonds are a pretty safe bet; it’s hard to manipulate the price of something as liquid as these securities. The big things to watch out for are the thinly traded assets that precipitated the rough ride in 2007 and 2008. Thanks to new accounting rules, companies now have to disclose the amount of assets they have in this category.

Conclusion

Mark-to-market accounting isn’t bad in and of itself. In fact, there are many times when marking assets to the market makes a company’s books more accurate than leaving the items at cost. The easiest way to get a handle on how much of this accounting practice is going on is to read the footnotes attached to your stock’s reports.