Market Economy Advantages and Disadvantages

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Market Economy: Advantages and Disadvantages

By Bertell Ollman

(Talk at Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China—Oct. l999)

Reply to Prof. Kang Ouyang’s Article on Marxist Philosophy in China

We must all be thankful to Prof. Kang Ouyang for his clear and concise summary of the main tendencies in Marxist philosophy in China, a country whose development is becoming ever more important to the fate of the entire world. It is an impressive list. I was especially pleased to learn of the growing interest in Marx’s theory of alienation and his theory of truth, and of the widespread opposition to all kinds of dogmatism. The question now arises of how to interpret and judge Kang’s remarks in these and related areas. For this I can come up with no better criterion than the test of practice advanced by Kang himself (and also by Deng Xiaoping whose writings are so influential in China today). On the basis of this criterion, what is decisive is not what someone says or how well they say it, but what they do, what it gets them to do, and how successful that is. So what can we learn about contemporary Chinese Marxist philosophy from Kang’s practice in presenting it and from the real social practices that it has in large part inspired?

Considerations of space as well as my own limited familiarity with China makes a full evaluation of Kang’s wide ranging article impossible, so I will focus on only one area, market socialism or what is often referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics, which is also the area that I know best. My choice can also be justified on the grounds that this is the subject on which the new generation of Chinese scholars have made their most distinctive contribution and for which they are best known outside China. And here—it must be said—it is not a good sign that Kang’s account of China’s market economy offers us only one side of the picture, presenting only arguments that support the market and presenting only the positive results of China’s experience with the market. Practice cannot serve as a criterion for determining truth, progress, justice, alienation or, indeed, anything else unless everything that counts as practice is included in our treatment of the subject. Let me suggest what the main arguments both for and against the market (socialist as well as capitalist market) look like, and sketch how using the market has effected China, both for good and for bad. Through such rhetorical practice, my aim is to provide a helpful basis for evaluating both China’s experience with market socialism and Kang’s philosophical defense of it.

A market economy has seven main characteristics: l) people buy what they want, but only if they can pay for it; 2) thus, money becomes necessary for life; 3) people are forced to do anything and to sell anything in order to get money; 4) maximizing profit rather than satisfying social needs is the aim of all production and investment; 5) discipline over those who produce the wealth of society is no longer exercised by other people (as in slavery and feudalism) but by money and the conditions of work that one must accept in order to earn money; 6) rationing of scarce goods takes place through money (based on who has more than others) rather than through coupons (based on who has worked harder or longer or has a greater need for the good); and 7) since no one is kept from trying to get rich and everyone is paid for what they do, people acquire a sense that each person gets (and has gotten) what he deserves economically, in short, that both the rich and the poor are responsible for their fates.

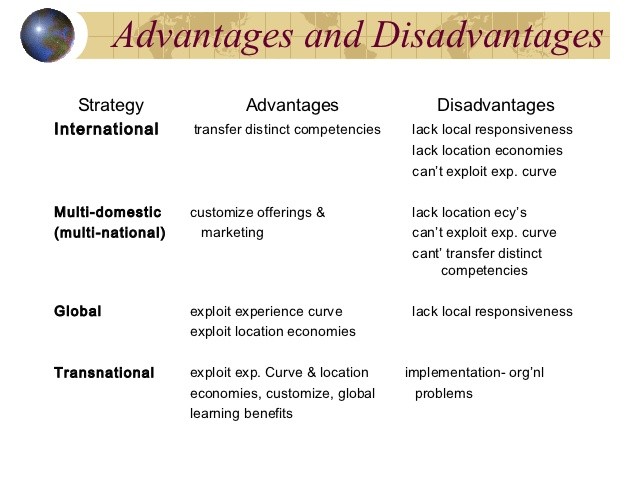

Whether the society is developed or underdeveloped, a market economy has several important advantages and several major disadvantages: Among the advantages, we find the following:

- Competition between different firms leads to increased efficiency, as firms do whatever is necessary—including laying off workers—to lower their costs;

These are the main advantages of the market economy, and in his article Professor Kang gives a good account of them. But, as I said, there are also major disadvantages, and these Kang neglects. Among the disadvantages, we find the following:

- Distorted investment priorities, as wealth gets directed into what will earn the largest profit and not into what most people really need (so public health, public education, and even dikes for periodically swollen rivers receive little attention);

Once we have recognized all the main advantages and disadvantages of the market economy, and once we have had a chance to examine and compare them, there are three major questions that remain to be answered. First, is it possible to have the advantages of the market economy without the disadvantages? Both theory and empirical evidence argue strongly that the answer is no. Even a quick perusal of Marx’s analysis of how the market economy works reveals it as an organic whole in which each part serves as an internal aspect in the functioning of the others. Similarly, their effects, both good and bad (what I’ve called advantages and disadvantages), entail one another; they are extended parts and/or necessary preconditions or effects of each other. For example, market experiences produce, of necessity, market personalities in people, and market personalities become a necessary precondition for people of all classes to engage in market relations effectively, and hence for the market to work as well as it does. You can’t, in other words, place people in market relations and expect them to retain very much of the socialist ideas, values and emotions that may once have had. And the same glue holds together all the economic, social and psychological aspects of a market economy.

For empirical evidence, just look at how quickly and how thoroughly China fell victim to all the disadvantages of the market once it set out to avail itself of the market’s advantages. The Chinese government would have liked nothing better than to avoid these crippling disadvantages. It simply was not possible.

A second key question is—is the equilibrium between the advantages and disadvantages of the market economy stable or changing? The answer is that they are constantly changing, and if changes sometimes favor the advantages (not by making the disadvantages disappear, which is impossible, but by making them appear smaller), the movement toward economic crisis that is taking place in all market economies today makes it clear that it is the disadvantages associated with the market that are becoming its most prominent features.

The third, and final, major question is—can people change their mind about the market? And the answer is—of course. They do so all the time, moving from against to in favor or from in favor to against. Just because a society opted for one approach to the market, let’s say 25 years ago, when one set of problems were dominant, is not in itself a good reason to retain this approach when another set of problems become far more pressing.

If the answers I have given to these three questions are correct, then the central problem facing China today might be posed as follows: Should China stick with the market economy in order to continue to benefit from what’s left of its advantages (and simply accept all the negatives that come with it), or—because the disadvantages have gotten so bad—should China now do whatever is necessary to deal with them (and treat whatever benefits it once got from the market as secondary)? It is, of course, not for me but for the Chinese people to say what should be done. I have only tried to clarify what is involved in making such a momentous decision, and, also—and now we return to Kang’s article—to suggest that it is only by fully laying out the main advantages and disadvantages of market socialism that any effective solution to China’s problems can be found. Anything less, any recourse to one-sidedness in confronting this situation, is bad economics and bad philosophy, Marxist or otherwise.

According to Kang, the core of Deng Xiaoping’s teachings is directed to emancipating the mind and seeking truth from facts. I can’t think of anything that is more important for us, for all of us, to do. The fate of China today hangs on how well the Chinese people—leaders, philosophers and ordinary people alike—can apply this advice to Deng’s own words and the social and economic reforms that have followed from them.