IPO The Initial Public Offering (IPO) Resource Page

Post on: 10 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

See /iporefs/ for a bibliography of work on IPOs. © Ivo Welch, 1996. This document is for the free use of all interested parties. However, this document must not be distributed, except in its entirety. Computer printouts are permitted, but further copies of printouts are not. Computer WWW references/links are expressly permitted. This site is listed at www.yahoo.com. The author is not liable for any false or misleading information in this WWW page.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This WWW page provides information on initial public offerings (IPO’s ). It is a first draft. To read more about the philosophy guiding this page, please read Appendix 2.

Should The Company Go Public?

Advantages

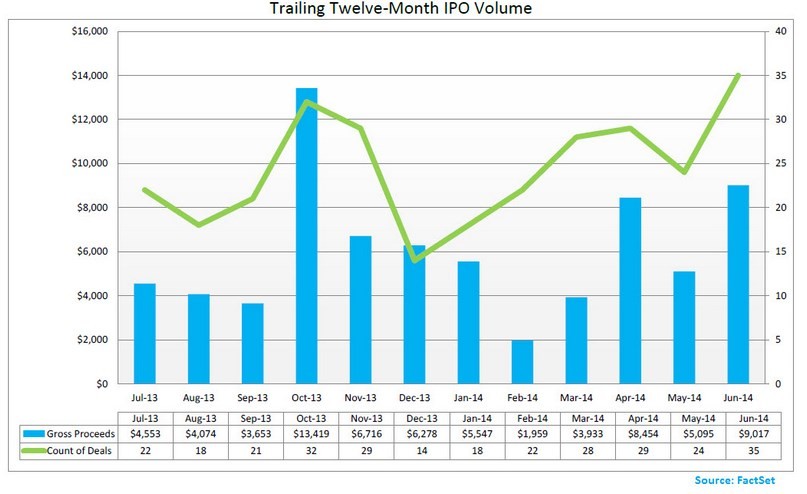

New Capital Almost all companies go public primarily because they need money. All other reasons are of secondary importance. The typical (firm-commitment) IPO raises $20-40M, but offerings of $100M are not unusual either. This can vary widely by industry. Some basic facts about the IPO market can be found in Table 1. Future Capital Once public, firms can easily go back to the public markets to raise more cash. Typically, about a third of all IPO issuers return to the public market within 5 years to issue a seasoned equity offering (the term secondary is used to denote shares sold by insiders rather than by firms). Those that do return raise about three times as much capital in their seasoned equity offerings as they raised in their IPO. Cashing Out Although it is a bad signal to investors when an entrepreneur sells his own shares (indicating that [s]he is jumping ship), it still makes sense for many entrepreneurs to cash out some of their wealth to diversify or just to enjoy life. Mergers and Acquisition Many private firms just do not appear on the radar screen of potential acquirors. Being public makes it easier for other companies to notice and evaluate the firm for potential synergies. Image Public firms tend to have higher profiles than private firms. This is important in industries where success requires customers and suppliers to make long-term commitments. For example, software requires training and no manager wants to buy software from a firm that may not be around for future upgrades, improvements, bug fixes, etc. Indeed, the suppliers’ and customers’ perception of company success is a self-fulfilling prophesy.

But public firms also tend to be larger to begin with, and this may explain why public firms on average have a better image. For example, although Gateway is private, there is no question that it will be around for a while. Going public would not aid increase its sales. The important question is if going public improves the firm’s stakeholders’ perception of success.

Employee Compensation Having a public share price makes it easy for firms to give employees a formal stake in the company.

Is the Time Right To Do an IPO ?

To be filled in.

What Advisors Should The Firm Hire?

Consultants

It is important for entrepreneurs to hire someone independently who understands IPO’s. preferably someone who understands IPO’s in the same industry. Auditors, lawyers, and underwriters all have interests conflicting with the entrepreneur’s interests. The auditors want to make sure they do not get sued and bill as many hours as possible. The lawyers want to never state anything in writing for which they can later be held liable, and also be paid as many hours as possible. The underwriters want to do the deal under conditions as favorable to them as possible, including pricing the offering low so as to minimize their necessary selling effort. When negotiating with the underwriter, it is imperative that the firm runs the numbers itself first!

This is not to say that experts are typically dishonest. Indeed, entrepreneurs need to build up mutual trust with their advisors to succeed. But at the same time, they should protect their own interests. An independent consultant can guide the appropriate selection, compensation, and behavior of other experts. The consultant should not be recommended by other experts: it is the consultant’s job to advise the firm how to work with the other experts. A cozy relationship between advisor and other experts can bias the consultants’ decision-making process. (Remember: after the IPO. the consultant will get little new business from the entrepreneur—but [s]he can get a lot of business from other IPO experts!)

It is astonishing how rarely independent advisors on relationships with IPO experts are retained by entrepreneurs, and how frequently independent advisors on relationships with IPO experts are retained by lawyers in law suits between firms and their former advisors lateron.

Auditors

Auditors are highly concentrated. The top 6 auditors (Ernst and Young, Arthur Anderson, Coopers and Lybrand, Deloitte and Touche, KPMG, Price Waterhouse) control about 90% of the IPO market (by dollar volume and roughly in the quoted order). So, the choice is easy: choose one of the Big-6. It helps getting the appropriate credibility with investors.

The cost of auditors’ services in the typical IPO ranges from $1K to $2M, with most firms paying between $100K and $300K. (Mean/Median/Stddev. were about $170K/$130K/$175K in 1990-dollars for 960 issuers in the 1992-1994 period.) Clearly, auditor cost varies mostly by firm size and age: more complex and older operations require more auditing. Offerings below $10M typically pay $50-100K, offerings above $100M typically pay $300-400K.

Lawyers

Lawyers are basically advisors. They typically are not liable/responsible. Their role is to make sure that documents conform to legal standards, and that participants are properly indemnified. Although there are a few law firms that are expert for IPO’s (and in a particular field), there are many more reasonable choices for legal services than for auditing services. Worth mentioning are Skadden Arps, and Wilson-Sonsini (computer industry expertise), but there are many other reasonable choices.

The cost of legal services in the typical IPO ranges from $5K to $2.5M, with most firms paying between $150K and $400K. (Mean/Median/Stddev. were about $255K/$202K/$175K in 1990-dollars for 960 issuers in the 1992-1994 period.) Offerings below $10M in size typically pay $100-200K, offerings above $100M typically pay $500K-700K.

Underwriters

The most important choice is the underwriter. The underwriter is the principal player in the IPO. providing the firm with Reputation Because the underwriter is legally liable and because the underwriter has ongoing dealings with the customers to whom he sells shares, the underwriter puts his reputation on the line. Finding Investors The underwriter first puts together a syndicate of other underwriters to distribute firm shares. The syndicate finds investors willing to put their money into the company. This has serious implications: Will the new investors be institutional or private? Is the company widely held or are shares concentrated with just a few investors? Will there be a lot of trading in the company in the aftermarket, or will there by long-term investors? Experience The underwriter knows the details of the process better than any other participant—unlike other participants, issuing shares is one of their primary business functions. Underwriters are the ones to provide proper guidance. Aftermarket Support For 30 days after the offering, a good underwriter provides price stabilization. This protects investors and makes the offering more attractive. It is important for the firm to have a clear understanding with the underwriter exactly how much support he/she plans to provide. Future Services The underwriter often provides post-IPO analyst coverage and market-making services. Most successful IPO’s return to the market to do a seasoned equity offering. A good relationship with an underwriter can save time and money in future offerings. Pre-Offering Sales The underwriter will conduct road-shows with the company’s management, distribute the preliminary prospectus, and talk to potential investors about appropriate pricing. Some part of the value potential shareholders attach to shares is directly generated by the marketing of the underwriters itself.

The services of good underwriters do not come cheap, however. Most IPO’s pay a flat 7% of the offering size to the underwriter, plus they grant an overallotment (green shoe) option, and on occasion pay significant legal expenses on top. (The entrepreneur should make sure to negotiate a cap.) Underwriters may request the right of first refusal to do future public offerings, but it is advisable for issuers either not to agree or to limit this right to 2-3 years. Also, underwriters prefer lower prices: lower prices make selling shares a lot easier, and allow the underwriter to reward his/her best customers by giving them share allotments. In a sense, pricing that is too low is an expense that an entrepreneur should factor into the costs of underwriting.

It is a good idea to solicit presentations from several investment banks. Professional underwriters understand that this is common business sense.

A (non-binding) price range is usually indicated in the preliminary prospectus, but the actual price is decided on the day before the IPO. Similarly, the scale of the offering (the number of shares) is decided on the first day. Entrepreneurs should not sell too many shares (for IPO’s are unusually expensive to conduct), but selling too few shares may limit the market liquidity and reduce the appeal to investors. It is of paramount importance that investors know the worth of their shares and the appropriate issuing size when negotiating with the underwriter for the appropriate price!

Virtually all reputable IPO’s in the United States are done via firm-commitment offerings, in which the underwriter guarantees that the shares will be sold. Both investors and reputable firms should stay away from best-efforts offerings, in which the underwriter is only an agent on behalf of the firm. This is not because the contract is intrinsically bad; instead, it is because no other reputable firms and underwriters seem to use it.

Among the 960 issues in the 1992-1994 period, the lowest underwriter compensation was 4% of the offering, the highest about 12%—but almost all offerings were between 5% and 9%. Offerings raising less than $10M paid about 7-9%, offerings raising more than $100M paid about 5.5-6.2%. The top underwriters were Goldman Sachs Merill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley, all of whom specialized in large size IPO’s .

Printers

Choosing the right printer used to be of importance in the past. But with printing costs down and advanced printing technology inhouse in most firms, this is no longer an important choice.

Tables: Find an appropriate advisor.

/experts.html contains expert (underwriter/lawyer/auditor) compensation and ratings up until the end of 1994.

Appropriate Underwriters