Investor relations in an increasingly regulated and international world Financial Conduct

Post on: 17 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Published: 19/06/2013 Last Modified: 18/07/2013 / Author: David Lawton

Speech by David Lawton, Director of Markets, the FCA, to the Investor Relations Society Annual Conference, on 18 June 2013.

Thank you for inviting me to speak at your annual conference. This keynote is billed as ‘IR in an increasingly regulated and international world’, which initially seemed liked an ambitious range to cover in a mere 30 minutes, but I hope to discuss some very significant developments and work affecting the investor relations space in that time.

There is nothing unique to the investor relations community in having to deal with an increasingly international environment. The growth in regulation is one component of having increasingly international financial markets. Firms (and consumers) are having to adjust to new expectations. The remit of regulation is responding to the need to ensure financial stability and adequate consumer protection, raising standards in transparency, capitalisation, systems and controls and conduct of business.  Alongside this, firms are having to engage with new regulatory authorities, including mine, the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA), as regulatory structures are redesigned and embedded post-crisis.

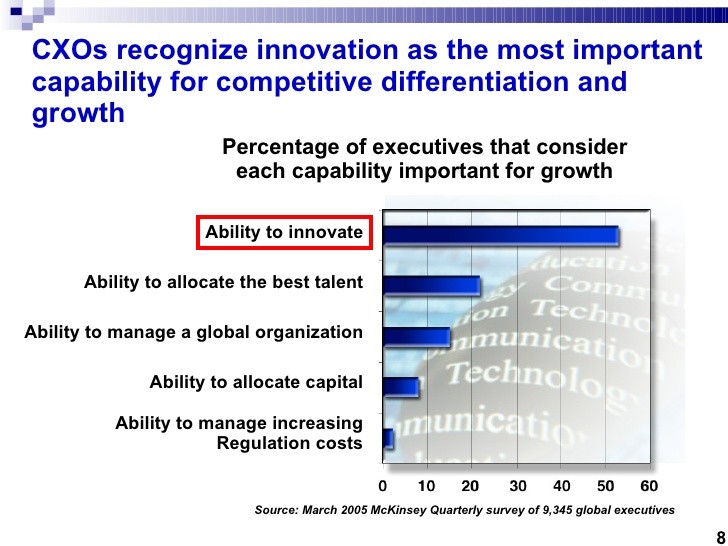

Taken in isolation, none of these developments are straightforward; taken in conjunction they create a complex step change for firms, regulated and unregulated.  But the same rules apply for success. The firms that are alert and quick to respond will be the ones that reap the benefits. I hope this speech will play a part in your efforts to be in that category.

During this speech, I will run through some key issues in the regulatory world for investor relations:

The UK’s new regulatory structure: The new regulatory structure is not yet three months old, so I think it is worth taking  a moment to outline what it is and what it means for the firms we regulate and the wider world.

The FCA’s objectives and approach: As Director of the FCA’s Markets Division, I will focus mainly on the markets agenda and in particular our work as the UK Listing Authority (UKLA).  Within that I will tackle how we deal with being the regulator of one of the most international Listing Regimes and the role you play as part of that. I will also touch on our work in wholesale conduct, in particular our thinking around corporate access.

Observations on the international landscape: To close I will make some high-level observations on the international landscape, including challenges for regulators and firms.

I am going to spend the bulk of my time focusing on the new regulatory structure and the FCA agenda. One of the comments from the Investor Relations Society to the recent FCA Transparency Discussion Paper was that it would welcome further information on the roles of PRA and FCA, as well as a better understanding of the FCA’s dual role as the UKLA. I will seek to address, at least in part, this request.

The new UK regulatory structure

The UK now has a new regulatory structure overseeing financial services. This is made up of:

- The Financial Policy Committee, which has the primary objective of identifying, monitoring and taking action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system. It has a secondary objective to support the economic policy of the Government.

The FCA’s objectives and approach

The FCA’s approach to the firms it regulates is governed by one single strategic objective: making relevant markets work well.

Underneath that strategic objective we have a new set of operational objectives:

- ensuring consumers get financial services and products that meet their needs from firms they can trust

The most obvious area where these objectives are different from the FCA’s predecessor is our new competition objective. This lets us think about the markets and firms we supervise in a different way. Just as for our other objectives, in pursuing the competition objective we have general rule-making powers, as well as the power to make firm specific orders. We will also be able to refer issues to the Office of Fair Trading (OFT).

We’ve set out our approach to this objective in a number of documents, and will further elaborate in a consultation we will publish in July, Advancing our objectives .

Consumer protection objective

The separation of roles between a prudential and a conduct authority gives us more space to focus on conduct issues and get to the substance of the drivers of poor conduct. The Financial Services Act 2012 defines ‘consumer’ in a broad sense. So our consumer protection objective is not confined to only retail consumers. This empowers us to reinvigorate our approach to wholesale conduct and take a more holistic approach in addressing conduct practices that affect both the wholesale and the retail consumer.

In reinvigorating our wholesale approach, this does not mean that we will be blind to the obvious. Wholesale consumers are more sophisticated than retail consumers and do not need the same protection as retail consumers or the same level of intervention by regulators. But our work will recognise three crucial things:

- The important continuum between wholesale and retail conduct, and how easily poor conduct in one can bleed into other areas and become pervasive through the financial system.

Integrity of UK financial services

As well as our consumer protection objective, we also have an objective to protect and enhance the integrity of the UK’s financial services. That objective recognises the cumulative importance of the firms we regulate, the systemic importance of the trading venues we supervise and our role as the UK’s primary markets regulator given London’s seat as a major international centre for capital raising.

Enhancements to the Listing Regime

Our UK financial services integrity objective speaks directly to our continuing work in maintaining the Listing Regime and keeping it fit for purpose.

The UK remains one of the pre-eminent jurisdictions for high quality global listings. The UK Listing regime has an offering which through a combination of factors is very attractive. That means a rich diversity of issuers and investors. With the benefits of that diversity also comes a spectrum of corporate governance and market practice expectations working within the UK.

It is important to recognise that the Listing Regime is only one element of the UK framework around corporate governance. To draw that point out, I would like to sketch out for you what the regime does and does not do.

Firstly what the regime does do.

The regime provides investors assurance that, at first admission, companies have met objective eligibility criteria. These criteria cover aspects such as the length of time the issuer has been operating for, and its ability to provide a clean working capital confirmation.

Once admitted, the regime provides a series of ongoing requirements which are largely disclosure based. The Listing Rules provide additional investor protections such as restrictions on the ability of directors to deal in their own securities or to transact directly with the issuer. With these requirements we maintain a carefully guarded gateway to listing, and particularly to the premium listing segment. These premium segment requirements are above the EU minima, but they do not speak to general board behaviour or governance.

There is a limit as to what assurance those requirements provide.

It is important to understand that the regime is not a suitability assessment for investors. Nor is it aligned to the criteria for inclusion in indices which a passive investment strategy might want to track. It sets out the behavioural and governance obligations that issuers must meet to gain access to capital. In approving a security for the Official List, the UK Listing Authority is making an assessment of the company against the obligations of the regime. Investors need to make their own assessments, because the UKLA is not making a suitability assessment.

And because the regime is limited to its requirements, the regime is not a catch-all for all corporate concerns. The Listing Regime sits within a wider net of UK Corporate Governance. The UK’s Corporate Governance Code is owned by the Financial Reporting Council, and is a code of best practice for the boards of listed companies.  This code is not mandatory – issuers are required either to comply with the Code, or to provide disclosure explaining the areas of non-compliance. The most serious concerns, which raise issues such as corruption, fraud or other criminality are matters for other authorities, including overseas enforcement agencies, not the UKLA.

For the Listing Regime to provide a meaningful tool to investors, it needs the participation of investors in the form of ongoing stewardship and consumer responsibility. The regime is designed to enable active investors to get sufficient information to make informed decisions whether to buy or sell the securities of those issuers. It assumes and requires shareholders – both individual and institutional – to be engaged and to hold to account the companies in which they invest.

And for those types of investors we work to keep the regime flexible, and strive to recognise in that regime the complexities of having a diverse range of firms applying to list in the UK.  A key part of having a flexible regime is staying vigilant to changing market practices. One of the challenging, and indeed interesting, parts of being a regulator is grappling with thorny issues, and maintaining the Listing Regime to keep pace with the market is one such example.

There has been commentary that our listing standards are too low in relation to some types of issuers.  While we do not agree with all of the commentary that has been provided in this area, we are certainly alive to the issues. And, specifically, we have already consulted on a package of rule changes which would tighten up the regime for issuers with controlling shareholders.

The Consultation Paper that we published last October on enhancements to the Listing Regime offered up no silver bullets for how to address this complex issue. And it is complex, because while there is a case for strengthening the protections for minority shareholders, this should not be at the expense of overturning the principle of majority control.

Our proposals, as you would expect, certainly did not receive a one note response from our stakeholders, nor were they intended to. One of the benefits of a wide range in views is that we can have a full debate and this will help us reach a balanced set of final proposals. The downside is that it we need to navigate through the views. Calibrating a regime like this is an art rather a science, and we are trying to find a mix of proposals, which working in concert deliver the best outcome. For that reason we are comfortable with taking the time to get this right. The broad direction of travel is still likely to be that foreshadowed in the Consultation Paper. We will set out our final proposals later in the summer.

Corporate access

I would like to move on now and talk about another area where our work touches on the interests of the investor relations community, corporate access.

The FCA defines corporate access as the practice of investment banks and brokers arranging for asset managers to meet with the senior management of corporates in which they might invest or already have invested in. Corporate access is not a new conversation for industry and the regulator but it is an important one because it speaks to the application of stewardship in the real world.

I have already said that a fundamental assumption of the Listing Regime is active investors and stewardship. So naturally we share the views of the IRS that meeting investors who are aligned to the Stewardship Code and the long-term interests of the company is of paramount importance.

And corporate access does not, by its definition, conflict with that goal. We recognise the benefits of corporate access, and the need for a dialogue between the senior management of corporates and key investors. Indeed it plays an important role in what, as I mentioned earlier we want to see in the market: active, engaged investors. But there is evidence that suggests that the current practices around corporate access need to be explored further.

Reports of investment banks charging asset managers several thousand pounds an hour to meet with CEOs of their investee companies suggests that some of the current practices could be pushing out the sort of long-term investors needed for good stewardship in favour of those willing to stump up the cash. No one comes out well in these kind of stories. We need to have a conversation about how industry can yield better the benefits of corporate access and improve practices so that corporate access supports long-term stewardship.

The other thread of our work in this area is around transparency in the costs charged to investors and the use of dealing commission. Data shows that the corporate access costs of the asset management sector are not going down. The most recent Thomson Reuters Extel survey shows that a quarter of what asset managers reward the sellside for is corporate access. Our recent supervisory work has highlighted to us that this an area where firms can do more work to manage their conflict of interest.  There is also scope for firms to provide investors with more assurance that they exercise the same degree of oversight of expenses paid by the fund as they would if they paid for the same services themselves. This is an area where we believe greater transparency over cost would be of advantage to clients. We will have a full and open discussion with industry to reach the right outcome for investors and help build further trust in the sector.

Observations on the international landscape

I am conscious that, for a speech billed as speaking on an increasingly international and regulated world, I have said very little on the point of international regulation.

The main point I want to make here is we have a huge regulatory agenda shared globally by regulators. The advantage of this for international firms is that this agenda is across jurisdictions, clustered around the same topics –for example, capital and liquidity through Basel III and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) IV, over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives through European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR), Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MIFIR) and Dodd Frank and global efforts to address remuneration.

International firms now need to keep engaged with multiple regimes and have systems that can meet requirements which, while they may be aiming at the same goal of greater financial stability, meet that goal in differing ways. Going back to my original point, there is no easy solution here but the firms that will cope the best will be those that engage early with the legislation, not at the point of implementation, but far earlier and who think carefully through how multiple jurisdictions interact and affect their business.

The challenge to this is ensuring that regulators are aligned and coordinated in their approaches. What we do not want are outcomes which create obstacles to market access, add unnecessary costs and have the effect of unnecessarily preventing economic activity from taking place. Efforts need to remain outcome focused and look to be based on reciprocal arrangements where possible.

At a European level, a key contribution to ensuring consistency comes from the new European Supervisory Authorities. The European Banking Authority (EBA), European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) provide valuable tools in harmonising standards and supporting coordination across European member states, and indeed are now becoming  regulatory supervisors in their own right. ESMA, for example, is now the supervisor of credit rating agencies and trade repositories, both of which provide key services to markets.

Internationally, the work of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) is helping to facilitate the same outcome, developing international standards that are sufficiently detailed and well implemented to limit arbitrage between jurisdictions.

I think a continued coordinated response to regulatory measures is an achievable goal. It would be a shame not to reach this optimal outcome after the international collaboration that has so far been achieved during the crisis.

Conclusion

There are new elements that firms need to deal with in what is increasingly a more regulated and international environment.

The creation of the PRA and FCA gives us new powers and objectives in relation to consumer protection, the integrity of the UK financial services and competition.

The FCA is taking the opportunity to expand and refine our approach to conduct risk. You should expect to see more activity in this area than in the past, both in the retail and wholesale space but also more dialogue with industry. I have given the two examples of the Listing Regime and corporate access where the FCA wants to have with industry an open and broad debate. I hope you will take up that challenge and engage with us.

Changes in the regulatory structure and its perimeter are not only at a domestic level, but also at an international level too. This will mean more actors in the local and global conversations on investor protection and financial stability. The firms that work best in this environment will  be those who make the effort to be part of a constructive dialogue and engage early with their regulators.