InvestmentCash Flow Sensitivities Constrained versus Unconstrained Firms

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities: Constrained versus Unconstrained Firms

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities:

Constrained versus Unconstrained Frrms

NATHALIE MOYEN*

ABSTRACT

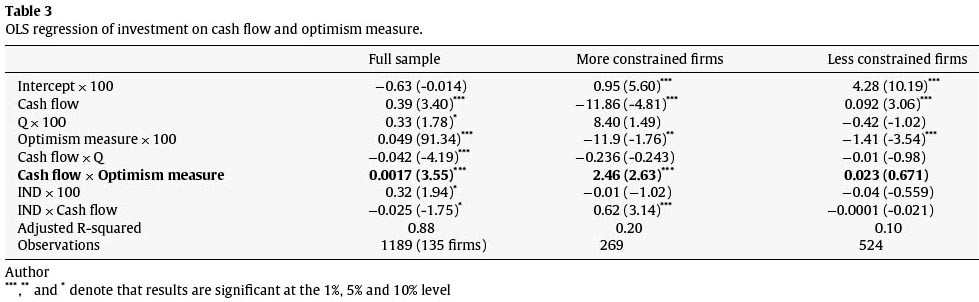

From the existing literature, it is not clear what effect financing constraints have

on the sensitivities of firms investment to their cash flow. I propose an explanation

that reconciles the conflicting empirical evidence. I present two models: the unconstrained

model, in which firms can raise external funds, and the constrained model, in

which firms cannot do so. Using low dividends to identify financing constraints in my

generated panel of data produces results consistent with those of Fazzari, Hubbard,

and Petersen; using the constrained model produces results consistent with those of

Kaplan and Zingales.

THE LITERATURE DOCUMENTING the sensitivity offirms investment to fluctuations

in their internal funds, initiated by Fazzari, Hubbard, and Petersen (1988), is

large and growing. The sensitivity is measured by the coefficient obtained from

regressing investment on cash flow, controlling for investment opportunities

using Tobins Q. Fazzari et al. view firms as constrained when external financing

is too expensive. In that case, firms must use internal funds to finance

their investments rather than to payout dividends. Fazzari et al. identify firms

with low dividends as Most constrained and firms with high dividends as

Least constrained. As reported in Table I, Most constrained firms have investments

that are more sensitive to cash flows than Least constrained firms.

Kaplan and Zingales (1997) disagree with the interpretation of the result. Their

identification of financially constrained firms is based on the qualitative and

quantitative information contained in the firms various reports. Kaplan and

Zingales identify firms without access to more funds than needed to finance

their investment as Likely constrained and firms with access to more funds

than needed to finance their investment as Never constrained. In contrast to

Fazzari et al. Kaplan and Zingales do not consider firms that choose to pay

low dividends even though they could payout more as constrained. As Table I

indicates, the investments of Likely constrained firms are less sensitive to

Never constrained 0.702 0.009

(0.041) (0.006)

empirical evidence, I construct two models: an unconstrained model, in which

firms have perfect access to external financial markets, and a constrained

model, in which firms have no access. Section I presents the two models, and

Section II describes the calibration necessary to solve the models. Series are

simulated from the two models and pooled to represent the theoretical sample.

Using this laboratory, I investigate whether the empirical results can be

replicated. I find that they can. Section III discusses two main findings. First,

using low dividends to identify firms with financing constraints leads to Fazzari

et al.s result that low-dividend firms investment is more sensitive to cash flow

than high-dividend firms investment. Second, using the constrained model to

identify firms with financing constraints leads to Kaplan and Zingaless result

that constrained firms investment is less sensitive to cash flow than unconstrained

firms investment.

The fact that the cash flow sensitivity of firms described by the constrained

model is lower than the cash flow sensitivity of firms described by the unconstrained

model can be easily explained. In both models, cash flow is highly

correlated with investment opportunities. With more favorable opportunities,

both constrained and unconstrained firms invest more. With more favorable

opportunities, unconstrained firms also issue debt to fund additional investment.

Because the effect of debt financing on investment is not taken into

account by the regression specification, it magnifies the cash flow sensitivity of

unconstrained firms. Also, given more cash flow, unconstrained firms use debt

to increase both their investment and their dividend payment. Constrained

firms choose whether to allocate their cash flows to more investment or more

dividends. The link between investment and cash flow is therefore weaker for

constrained firms. In accord with Kaplan and Zingaless result, the cash flow

sensitivity of constrained firms is lower than that of unconstrained firms.

The fact that the cash flow sensitivity of low-dividend firms is higher than the

cash flow sensitivity of high-dividend firms can also be easily explained. Firms

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities 2063

from the unconstrained model invest more than firms from the constrained

model. Because unconstrained firms can adjust their debt levels through time,

they also take on more debt. Debt claimants of unconstrained firms account

for a greater portion of the firms than debt claimants of constrained firms.

Equity claimants of unconstrained firms receive smaller dividends than equity

claimants of constrained firms. Using low dividends to identify firms with financing

constraints leads to Fazzari et al.s result. Low-dividend firms are

mostly firms from the unconstrained model, which exhibit a higher cash flow

sensitivity than do firms from the constrained model.

While the empirical debate between Fazzari et al. and Kaplan and Zingales

remains unresolved, a number of theoretical papers have investigated the sensitivity

of investment to cash flow fluctuations. Using a neoclassical framework,

Gomes (2001) and Alti (2003) show that cash flow sensitivities can be generated

from an environment without any financing friction. Both Gomes and Alti

conclude that cash flow sensitivities do not necessarily indicate the presence of

financing constraints. In contrast, I investigate whether financing constraints

are sufficient to replicate the empirical evidence underlying the Fazzari et al.

and Zingales debate.

Other papers use a finance framework to examine the cash flow sensitivity

controversy. Almeida and Campello (2001) develop a one-period model in which

firms may face credit constraints. Unconstrained firms show no cash flow sensitivity,

while credit-constrained firms exhibit a positive cash flow sensitivity. The

sensitivity of credit-constrained firms increases with their available collateral.

Instead ofimposing credit constraints on investment, Povel and Raith (2001) develop

a one-period model in which investment is not observable by the market.

They find that the relation between investment and cash flow is U-shaped, and

that more information asymmetry generally increases the cash flow sensitivity.

Like Povel and Raith, Dasgupta and Sengupta (2002) assume that investment

is not observable by the market. Using a two-period model, they also find that

the relation between investment and cash flow is not monotonic. In contrast, I

focus on the dynamic behavior of firms investment policies in an environment

with complete information.

I. The Models

I compare the investment behavior of two types of firms. The first type of

firm faces no financing constraint and trades off the costs and benefits of external

financing, while the second type of firm is completely shut out of external

financial markets. Using such extreme types of firms maximizes the effect of

1 Some empirical papers provide support for Fazzari et al. while others obtain results consistent

with those of Kaplan and Zingales. The papers providing support for Fazzari et al. (1988)

include Allayannis and Mozumdar (2001), Fazzari, Hubbard, and Petersen (2000), Gilchrist and

Himmelberg (1995), Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein (1991), Oliner and Rudebusch (1992), and

Schaller (1993). See Hubbard (1998) for an extensive literature review. The papers providing support

for Kaplan and Zingales (1997) include Cleary (1999), Kadapakkam, Kumar, and Riddick

(1998), and Kaplan and Zingales (2000).

2064 The Journal ofFinance

financing constraints on the cash flow sensitivity. In other words, the cash flow

sensitivity of constrained firms is as different as possible from that of unconstrained

firms.

A. The Unconstrained Firm Model

The unconstrained firm model characterizes the investment and financing

decisions offirms that face no financing constraint. Firms trade off a tax benefit

The firm maximizes the equity value subject to fairly pricing any debt issue

by choosing its dividend, investment, and debt policies. All claimants, equity

and debt, are risk-neutral. The unconstrained equity value VU is

(1)

where the superscript u denotes unconstrained firms, r is the discount rate,

and E, is the conditional expectation at period t. For simplicity, dividends and

capital gains are assumed to be untaxed.

Equation (1) shows that the equity value is the sum of the expected discounted

stream of dividends, DU. Equation (1) also shows that equity claimants

are protected by limited liability. Equity claimants default whenever Dr+ llr

Et[Vr+l] :s o. The firm may ask its equity claimants to contribute additional

funds (Dr < 0), but equity claimants may choose to relinquish their equity claim

rather than contribute more. In the case where the equity issue is not justified

by the expected discounted future equity value (Dr+ llr Et[Vr+l] :s 0), equity

claimants exercise their option of not contributing additional funds to the firm

and trigger default instead.

The firms sources-and-uses-of-funds equation defines the dividend

where Tf is the firms tax rate, K, is the capital stock, ()t describes the firms underlying

income shock, (1 — Tf )f(Kt ; ()t) is the after-tax operating income before

depreciation, 8 is the depreciation rate, Tf8Kt is the depreciation tax shield, It is

the investment,

Bt+l is the new debt issue, Lt is the interest rate, B, is the debt

level, and (1 — Tf )LtBt is the after-tax interest payment. The depreciation rate

used for tax purposes is assumed to be equal to the true economic depreciation

rate of the capital stock.

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities 2065

The firms operating income before depreciation is the difference between its

Equation (6) shows that debt claimants demand an interest rate such that

the debt lent to the firm this period equals next periods expected discounted

payoff The payoff on the debt claim consists of the face value Bt+1 and the

after-tax interest payment (1 — Tt)lt+1Bt+1 if equity claimants do not default,

or the net residual value R(Kt+1;Ot+1) — XBt+1 if they default, where t, is the

debt claimants interest income tax rate, X is the deadweight default cost as a

proportion of the debt face value, and the function l(v>o) indicates no-default:

1 if V > 0,

l(v>o) == o otherwi.se.

The residual accruing to debt claimants upon default R(K; (>)is the reorganized

value of the firm. Debt claimants may then recapitalize the firm in an optimal

2 Rather than representing labor expenses as a fixed cost F, one could explicitly model the firms

labor demand decision. The firm would gain another instrument to maximize its value. The firms

operating income would become more responsive to the income shock ()t. The firm would hire more

labor in periods of high income shock and less labor in periods of low income shock. Not explicitly

modeling the labor decision makes the firms income less responsive to its shock.

2066 The Journal ofFinance

(9)

manner. In fact, R(K; () takes into account the optimal recapitalization from

that unlevered state

R(Kt; ()t) = (1 — r f) f(Kt; ()t) + 1:foKt — It + Bt+ 1 + -1-Et[V/

The firms income shock is represented by a first-order autoregressive process

with persistence p and volatility a:

In ()t+l = pIn ()t+aEt+l, (11)

where Et

i.i.d. N(O, 1). Because the persistence parameter p is not zero, the

income shock is somewhat predictable. The firm anticipates the income shock

it will face next period and chooses its investment and debt policies accordingly.

The firm cannot perfectly anticipate the income shock it will face next period.

Although the firm positions itself to limit the possibility of default next

period, default occurs when next periods income shock ()t+l turns out to be so

much lower than expected that the equity claim becomes worthless. The income

shock at which equity claimants trigger default (>U(Kt. Bt. It) is defined by Dr + llrEt[Vr+l] = o. If we substitute equations (2)-(5) into this expression,

the default point is implicitly defined by

(1- if )((>U(Kt, Bt. It)K

- F) +(1- (1- if )o)Kt — K t+ 1 + Bt+ 1

l lOt = (>U(Kt, Bt, It)] = O. (12)

not restricted to be nonnegative. The firm is allowed to sell some assets and

to retire debt. There is no need for a stock of cash in the model. The firm can

effectively manage its probability of default by buying and selling its capital

stock and by changing its financial structure.

The firm chooses how much dividend Dr to pay, how much to invest It, and how

Bt+1 at the interest rate It+1 that satisfies the bond-pricing

equation (6), in order to maximize the equity value in equation (1) subject to

equations (2)-(5). The firm makes these decisions after observing the beginningof-

aKt+1 alt+1

are defined in the Appendix.

Equation (14) states that the firm invests up to the point where the cost of one

unit of capital equals next periods expected discounted marginal contribution

to dividends. Equation (14) also shows that the firm accounts for the effects of

its investment decision on the interest rate requested by debt claimants and on

the default probability. A higher interest rate It+1 promised to debt claimants

a[eU (K t+1, Bt+l, [t+l)]. a[eU (K t+1, Bt+l, [t+l)]),

defined in the Appendix.

The model cannot be solved analytically. The solution is approximated using

numerical methods. Once decision rules are obtained, a panel of firms is

simulated and studied.

B. The Constrained Firm Model

Without access to external markets, the model is simpler. The firms problem

is to choose its dividend D, and investment It policies to maximize the equity

value. The firm finances itself neither with debt (Bt+1 == Bt == 0) nor with equity

0). The model recognizes, however, that constrained firms are levered, as

has been documented by Fazzari et al. and by Kaplan and Zingales. It is possible

that a constrained firm has had access to external capital markets at some point

in the past, no longer has access, but is still servicing an existing debt structure.

The debt in place is assumed to be a perpetuity. The interest payment c of the

constrained firm does not vary through time, because the firm no longer has

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities

subject to the dividend equation

the income equation (3), and the capital accumulation equation (4).

The investment decision is characterized by

where At is the multiplier disallowing equity issues. Equation (18) states that

r == 0.95, and the depreciation rate [)

to 0.1. The tax rates are calibrated to reflect the U.S. corporate and personal tax

rates of 40% and 20%: if == 0.4 and it == 0.2. The default cost is set toX == 0.1, as

a compromise between Fischer, Heinkel, and Zechner (1989) and Kane, Marcus,

and McDonald (1984), who calibrate this cost to 5% and 15% of the debt face

value.

Moyen (1999) estimates the sensitivity parameter (1, the persistence p, and

the volatility a from annual COMPUSTAT data using the firms income equation

(3) and the autoregressive income shock process of equation (11). Accordingly,

the sensitivity of the firms income-to-capital stock variations is set to

(1 == 0.45, the persistence to p == 0.6, and the volatility to a == 0.2.

The long-term coupon is set to C == 0.15 to maximize the ex ante constrained

firm value Vo+Lo, where the perpetual debt value L, is defined in the next

2070 The Journal ofFinance

section. The coupon is expressed in relation to the numeraire, which is the

value ofa unit ofincomef(Kt. Bt ). For example, ifincome were scaled to $f(Kt. Bt )

millions, the coupon per period to be paid by the firm would be $150,000.

The fixed cost representing labor and other expenses F is calibrated to obtain

a reasonable average debt-to-capital stock ratio of 0.6. In the constrained firm

model, this debt-to-capital stock ratio is obtained with a fixed cost of 0.45.

In the unconstrained firm model, this debt-to-capital stock ratio is obtained

with a higher fixed cost of 1.35.3 A higher fixed cost simply reduces the debt

level that can be serviced by the firm. As is discussed below, constrained firms

turn out to be smaller on average than unconstrained firms. When I calibrate

the fixed labor cost to obtain a reasonable debt-to-capital stock ratio, smaller

constrained firms appropriately face a smaller cost than larger unconstrained

firms.

Given these parameter values, the two models are solved numerically as

described in the Appendix. The resulting series It, t,.Bt+1. It+1, and Vt are simulated

from random outcomes of the income shock Et. A sample of 1,000 unconstrained

firms and 1,000 constrained firms is generated, where each series for

which no default v, > 0 occurs for at least 10 consecutive periods defines a firm.

I simulate an equal number of constrained and unconstrained firms because

it is difficult to know how many firms in the data currently have easy access

to external markets. The robustness of the results to different proportions of

these two types of firms is discussed in the next section.

Unconstrained firms sometimes default. For example, 0.69% of the unconstrained

firms default in periods 11-20. Equity claimants sometimes choose a

debt level that is too burdensome to service when next periods income shock

turns out to be much lower than expected. Constrained firms do not default.

The perpetual coupon chosen ex ante to maximize the firm value is not high

enough to generate zero dividends forever.

III. Results

A. Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities

Table II shows that the cash flow sensitivity of firms identified as experiencing

financing constraints may be higher or lower than that of firms identified

as experiencing no constraint, depending on the identification criterion used.

The simulated sample of2,000 firms over 10 periods is divided into two groups,

firms with financing constraints and firms without constraint, on the basis of

five criteria. Firms are alternatively identified as experiencing financing constraints

if they have low dividends, if they have low cash flows, if they are

indeed constrained as described by the constrained firm model, if they are described

by the constrained firm model and exhaust their internal funds when

investing, or if they have low Clearys (1999) index values.

3 The results are robust to different labor cost F values. A sensitivity analysis is available upon

request.

Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities 2071

Table II

Regression Results from Simulated Series

The measure K denotes the capital stock, CF cash flow,QTobins average q, D+ dividend, Athe multiplier

disallowing equity issues in the constrained firm model, and ZFC the financial constraints

index developed by Cleary (1999). Standard errors appear in parentheses. The portions of firm-year

observations identified as experiencing financing constraint, appear in brackets. The difference in

cash flow sensitivities between firms with financing constraints and firms with no constraint is

statistically significant at the 5% level for all regressions.

Firms identified by dividends:

Financing constraints-firms with low If-

No constraint-firms with high If-

Firms identified by cash flows:

Financing constraints-firms with low fJNo

constraint-firms with high fJFirms

identified by models:

Financing constraints-firms from the constrained model

No constraint-firms from the unconstrained model