Investment trusts versus unit trusts the differences

Post on: 14 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Related Articles

What are unit trusts and OEICs?

What are split capital investment trusts?

Favourite unit trusts & OEICs

Whats the difference between a unit trust and an investment trust? In this helpful guide, What Investment looks at the pros and cons of each.

Unit trusts and investment trusts are two types of funds that you can invest in as a private investor in the UK.

Unit trusts are also referred to as open-ended funds, because they will always accept more cash from investors they just become bigger to accommodate the demand. On the flip side, if there are more sellers than buyers, the fund will become smaller.

Investment trusts are also known as closed-ended funds, because they tend to raise a set amount of cash, then invest it. They do not create new shares whenever someone wants to buy them. Instead, they are listed on the stock market, so if you want to invest in them, you can buy their shares just as you would with any other listed company.

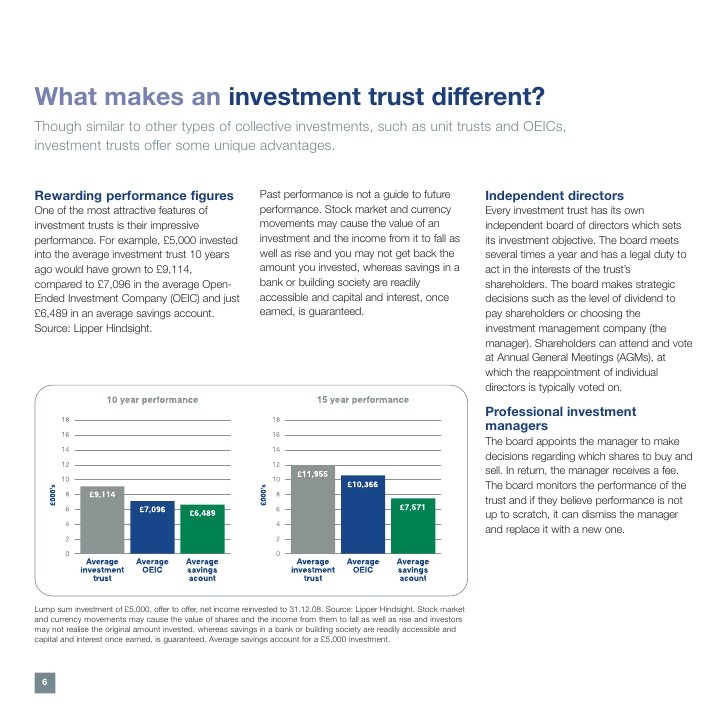

When choosing between unit trusts and investment trusts, the most important factor for any investor is without doubt performance. Research on the performance of investment trusts versus unit trusts (see here, for example ) regularly shows that investment trusts regularly do better in the vast majority of sectors when you look at longer periods of ten years or more. There are a number of reasons for this, which we talk about below.

However, if you look at a shorter period, say one to five years, investment trusts are less likely to beat unit trusts. They also offer investors a bumpier investment journey, with more exaggerated ups and downs in their share prices. For investors fond of the quiet life, unit trusts are attractive because they are less volatile. They are also a bit simpler to understand, for reasons well explain.

The important thing to remember is that there are plenty of open-ended funds that have consistently delivered great returns, and plenty of investment trusts that have performed drastically badly. It just seems to be the case that the average investment trust does better, in the long run, than the average unit trust.

Why do investment trusts outperform?

Inquisitive investors will want to know whether there are theoretical reasons for this performance gap.

One reason is that investment trusts allow managers to take a longer-term view. This is because they do not have to sell assets when investors sell their shares. In contrast, unit trusts do have to liquidate assets if investors want out, so do not bounce back up again so quickly as asset prices recover.

This effect is made worse by the fact that investors tend to want to exit their investments when the market is doing badly. This, of course, is the worst possible time to sell assets.

For this reason, investment trusts are more suitable for assets that are hard to sell quickly, like property and infrastructure. Unit trusts have to stick to easily sold (liquid ) assets, like shares. All the same, in a difficult market they will struggle to offload their bad assets, so will be forced to sell their good ones.

Another advantage investment trust managers have is that they can accrue revenue reserves. Unit trusts distribute their income on an annual basis, while investment trusts can keep up to 15 per cent of it in reserve for a rainy day. Despite the widespread dividend cuts around 2008 and 2009, many investment trusts were still able to maintain their records of paying out and growing dividends even in the face of a drop in underlying earnings.

In this way, investment trusts have the ability to preserve cash in good times and distribute it in bad times, thereby keeping income steady for shareholders.

Investment trusts are also subject to market discipline. If performance dips, the board of the investment trust can hold the fund manager to account and, in extreme cases, replace him. In theory, this separation between the trusts board and the fund manager should act in shareholders best interests.

A final reason for the difference in performance over the long term is the fact that many investment trusts (though not all) use gearing. This is a technical term for borrowing money, which provides a boost to returns when markets rise, as well as a drag when they fall.

Say you have 1,000 of assets to invest, borrow 300 on top of that, and then invest it all in a particular stock. That stock then doubles, leaving you with 2,600. Even after youve paid the 300 back with 10 per cent interest (say), youve still got 2,270 left. If you hadnt borrowed the 300, youd only have 2,000.

But what if the stock halves instead of doubles? As well as losing half your investment, you then have to pay back the 300 with interest, leaving you with only 320. If you hadnt used gearing, youd have 500.

So gearing helps to explain why investment trusts do better than unit trusts over the long term if markets rise but perform in a more volatile (bumpy) kind of way.

Buying unit trusts and investment trusts

Unit trusts are only priced once a day, so potential investors do not have perfect visibility over the price they will have to pay. Investment trusts are traded freely over the stock market, so investors generally have better sight of what they will have to pay for shares, although they will have to cope with the bid-offer spread and dealing costs (see below).

Shareholders in investment trusts can further benefit if the shares are undervalued (discounted ). This happens when the price of each share is less than the value of all assets held in the company divided by the number of shares (known as net asset value or NAV per share).

Although there is nothing to say this discount to NAV will definitely narrow, it offers investors willing to take on risk the chance to boost their returns. Investors can potentially buy in at a discount and then, as market sentiment revives, reap the rewards of improvements in both the underlying value of the assets and the narrowing of the discount or at least thats the hope.

The flip side of this argument is that the separation between share price and NAV introduces an element of complexity and unpredictability into investment trusts. If you buy at a premium and sell at a discount, youll do worse than someone who invested in an equivalent unit trust.

At the beginning of 2014, the average discount of all investment trusts was narrower than at any time since records began in 1970, so there are now far fewer opportunities to purchase investment trusts at attractive discounts than they were. The most popular investment trusts even trade at substantial premiums, which of course makes them less attractive to someone looking to buy in.

Fees and charges

The two vehicles are similar in terms of cost. Fans of investment trusts argue that theyre cheaper because they have lower running expenses, but this is hard to quantify because some of their costs are absorbed in the company accounts.

Broadly speaking, annual management charges at both range from 0.5 per cent to 1 per cent, so investors are advised to check on a trust-by-trust basis. Both unit trusts and investment trusts that invest in specialist areas, such as property or emerging markets, are likely to have higher fees. Investment trusts, in particular, may have performance fees that are paid when the trust beats a particular benchmark.

There are other fees and costs to bear in mind. For unit trusts, theres an initial charge. a one-off payment which is a percentage of the amount invested (usually 4 or 5 per cent). This is heavily discounted, often to zero, when you invest through online fund platforms.

There are also the fees and charges you pay to an investment platform (or execution-only broker. or fund supermarket ) to trade and hold the two types of funds.

Platform fees and dealing fees have seen vast changes following a body of legislation called the Retail Distribution Review (RDR), and they vary greatly from one platform to another.

However, what has not changed is that platforms charge differently for unit trusts and investment trusts.

To generalise, if you are not going to be trading very frequently and you have at least 10,000 invested, you are almost certainly going to pay less in platform and dealing fees with investment trusts as opposed to unit trusts.

This is because platforms tend to charge a percentage fee for your holdings in open-ended funds, which is either uncapped or capped at a very high level. For investment trusts, platforms may charge a flat fee, no fee, or a percentage fee with a lower cap.

Bear in mind, though, that many platforms do not charge you to buy or sell unit trusts, but all platforms will charge you to deal in investment trusts.

Bid-offer spread

Those buying shares in an investment trust will also notice that the offer price (the price at which you can buy shares) is higher than the bid price (the price you would be offered for your shares if you wanted to sell them). This dual pricing is so your broker can make money from the transaction.

Open-ended funds used to have a bid and offer price too, but most have now converted to a new kind of legal structure called an open-ended investment company (OEIC) which just has a single price whether you are buying or selling.

One confusing thing is that the term unit trust technically refers to those open-ended funds that use dual pricing. However, many people in the investment industry use the term unit trust to refer to both unit trusts and OEICs, as we have done in this article.

You do not have to choose between unit trusts and investment trusts, of course: many investors hold a mixture of the two. The most important thing is not the type of vehicle, but the managers ability to outperform the market .

Guide originally published: 15/8/12. Updated: 3/4/14.

Related investment guides

Building a portfolio get the right balance of investments