Intangible Assets Identification And Valuation

Post on: 20 Май, 2015 No Comment

Intangible assets (resources) play a fundamental role in economies’ change, from traditional scale-based manufacturing to new innovation-oriented activities. Intellectual property, R&D, workforce training, brand, software, organizational capabilities, etc. all play a critical role since the content of knowledge and sophisticated capabilities incorporated in products and services have dramatically increased in the course of the last century. The increasing relevance of intangible assets can be also verified from a macroeconomic perspective. In 1999 Nakamura, using a broad definition of intangible investments, evaluated the U.S. gross investment in intangibles to be one trillion dollars annually ( Nakamura 1999 ). According to a 2006 Federal Reserve Board analysis, investments in intangibles assets exceed all investments in tangible property ( Corrado et al. 2006 ) .

Advertisement

Our ability to measure and evaluate the phenomenon, at the level of an individual enterprise and at a national level, is still very limited, since current measurement and evaluation methodologies are still in large part the result of theoretical attitudes that attribute to physical assets the role of main value drivers. The problem also extends to the capital theory. Shifting from an agricultural economy to a mercantile, and then later, industrial economy, the capital has become a specific production factor, which traditionally consists of a group—whose value is measurable—of durable goods that can be used in production processes and to which economic actors may claim a property right (capitalists).

The concept later evolved, especially in the second half of the twentieth century, clearly shifting towards intangible, social and dynamic dimensions. The resulting scenario is on a theoretical level still in progress and it may also lead to a deep reconsideration of the traditional meaning of production factor . a fact that in part has already occurred in the theories of endogenous growth ( Dean & Kretschmer 2007 ). In the meantime, however, the role of intangible assets is increasingly more relevant and the evaluation tools remain inadequate (Bismuth 2006).

Accounting. Finance, Management and Strategy have tackled the problem of intangibles. As a result, analytical models have emerged, which are rather different from one another and can be classified into one of the following approaches ( Sveiby 1997, 2002 ):

- Market Capitalization Methods (MCM). whereby intangible assets are estimated as a difference between the enterprise market value and the operating invested capital.

- Return on assets (ROA). which is based on a calculation procedure that allows to go from profitability of the enterprise to profitability of intangible assets and therefore their value.

- Direct estimate of the value of individual intangible assets (DIC = Direct Intellectual Capital methods).

- Methods based on scorecards (Scorecard Methods). whereby the individual elements of the intangible property are first identified and then measured using indicators of a non-monetary kind.

Identification Of Intangible Assets

The standard setters IASB and FASB have issued, respectively, the standards IAS 38 and SFAS 142 to regulate the accounting recognition of intangible assets. In both cases, other accounting standards are also important, in particular, the ones concerning the accounting treatment of business combinations, IFRS3 and SFAF 142 (recently revised).

The logics followed by the two standard setters are similar and, in this section and in the next one, we will try to describe their most significant features. It is necessary to mention that, within the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the IASB and the FASB (27 February 2006), which sets up a Roadmap of Convergence between IFRSs and US GAAP 20, a first reflection about the new logics of intangible assets’ accounting regulation has begun. The accounting process of any asset requires dealing first with the asset identification and then with its evaluation. In the case of intangible assets, the identification process presents, for obvious reasons, some specific difficulties.

From an accounting point of view, intangible assets can be defined as non-monetary assets without physical substance, which are controlled by the enterprise and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise (general criterion for the accounting of any asset) .

According to both the IAS 38 and the SFAS 141, intangible assets meet the identifiability criterion when :

- It is separable, i.e. is capable of being separated from the entity (sale, exchange, rent, etc.) either individually or together with a related contract, asset or liability; or

- The control of future economic benefits arising from the intangible is warranted by contractual or other legal rights.

The two criteria, conceptually linked, are proposed in an autonomous way ; that is to say that the legal control criterion leaves aside the separability possibility, as the separability criterion should leave aside the possibility of controlling the asset contractually or legally.

Another important aspect of the accounting of any asset is the recognition criterion that depends on :

- The probability that the expected future economic

- Benefits attributable to the asset will flow to the entity, and

- The probability that the cost of the assets can be measured reliably.

Let us verify the observance of the recognition criterion in relation to the way in which the intangible asset comes into the entity, that is to say, in relation to the fact that the intangible is separately acquired, acquired as part of a business combination or internally generated. Read on

Normally, when an intangible asset is separately acquired, it is possible to state that :

- The probability recognition criterion is always considered to be satisfy ed, since the price an entity pays to separately acquire an intangible asset reflects expectations about the probability that the expected future economic benefits embodied in the asset will flow to the entity;

- Its cost can usually be measured reliably; this is particularly so when the purchased consideration is in the form of cash or other monetary assets.

If an intangible asset is acquired as part of a business combination, the situation is, at least conceptually, different :

- The probability recognition criterion is normally satisfied, at least to the extent that the asset is identified according to the above-mentioned criteria;

- As regards the cost measurement, it necessary to remember that the intangible asset, according to both the IASB and the FASB, has to be recognized at its fair value: the recent process of accounting standards review (IFRS 3 and SFAS 141) leads us to assume that the fair value of intangible assets acquired as part of a business combination can always be measured reliably.

- As regards the internally generated intangible assets, the accounting standards are particularly restrictive. They provide specific exclusions about the possibility of identifying some internally generated intangible assets, because of the difficulty of distinguishing them from the internally generated goodwill. In particular, they prohibit the recognition of trademarks, trade names, newspaper mastheads, editorial rights, customer lists, and costs incurred to start up a business, to train employees, for advertising and promotional activities, and for partial or total enterprise reorganization.

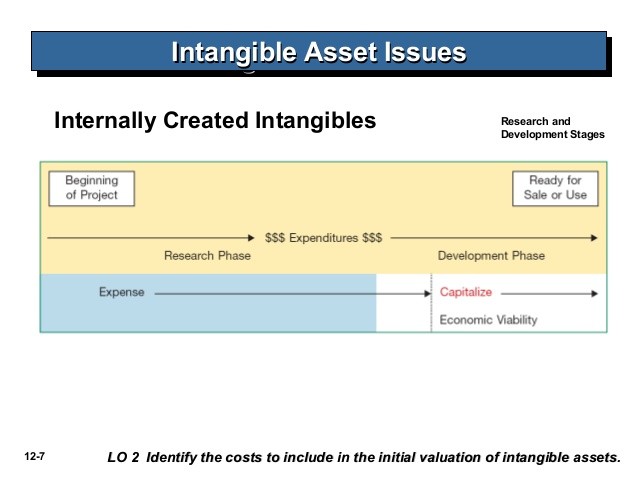

A specific matter concerns the research and development costs, treated in a detailed way by both IAS 38 and SFAS 2 (Accounting for the Research and Development costs): the first one, unlike the second one, provides the possibility of capitalizing costs associated with the development phase (and not the research phase) and just under specific conditions.

Illustrative Classification Of Intangible Assets

The SFAS 141 and the Illustrative Examples section of the IFRS 3 set up an illustrative classification of the different intangible assets that, acquired in a business combination, should, in different ways, meet the recognition criteria mentioned above .

The classification, even if just exemplifying, has a certain importance because it suggests an articulated prospect of intangible assets, classified into the following five groups :

- Marketing-related intangible assets (trademarks, trade names, service marks, certifi cation marks, collective marks, internet domain, trade dress, newspaper mastheads, non-competition agreement);

- Customer-related intangible assets (customer lists, order or production backlog, customer contracts and the related customer relationships, non-contractual customer relationships);

- Artistic-related intangible assets (copyrights for books, plays, films, music, pictures, photographs, operas and ballets, musical works such as compositions, song lyrics and advertising jingles, video and audiovisual material including films, music videos and television programmes);

- Contract-based intangible assets (licensing, royalty, standstill agreements, advertising, construction, management, service or supply contracts, lease agreements, construction permits, franchise agreements, broadcast rights, use rights, such as water, air, timber cutting, servicing contracts such as mortgage servicing contracts, employment contracts);

- Technology-based intangible assets (patented technology and unpatented technology, software, databases, trade secrets such as formulae, processes and recipes).

Evaluation Of Intangible Assets

For intangible assets separately acquired, the price paid by the acquirer represents the best indicator of its fair value. Also, for the intangible assets acquired in a business combination and recognized separately from goodwill, the fair value criterion is met .

However, in this case, since there is not a specific transfer price, the accounting standards set up a hierarchy of evaluation approaches :

- The quoted market price in an active market provides the most reliable estimate of the fair value of an intangible asset (IAS 38 defines an active market as one in which the items traded are homogeneous, willing buyers and sellers can normally be found at any time, prices are available to the public); the appropriate market price is usually the current bid price or, if the current bid price is unavailable, the price of the most recent similar transaction may provide a basis on which to estimate fair value;

- If no active market exists for an intangible asset, its fair value is the amount that the entity would have paid for the asset, at the acquisition date, on the basis of the best information available. to this purpose, the enterprise, besides considering the most recent transactions for identical or similar intangible assets, can develop other techniques for estimating intangible assets’ fair value, on the condition that these techniques reflect the practice of the industry to which the entity belongs: these techniques include the multiples approach (to revenues, market shares, operating profit) or the royalty stream that the entity could obtain from licensing the intangible asset (as in the relief from royalty approach), and the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) approach, that consists of discounting the estimated future net cash flow from the asset.

- Finally, just concerning IAS 38, the costs associated with an asset internally generated through the development phase are capitalized. All the above mentioned are valid for the initial recognition. After the initial recognition, the evaluation approach changes according to whether the intangible assets have a finite or an indefinite useful life.

In the first case, the intangible asset is amortized, whereas in the second case, the intangible asset is not amortized but it is subjected, at least once a year, to the impairment test, dealing with goodwill acquired in a business combination. The intangible assets impairment test requires in-depth discussion because it includes some important evaluation suggestions. For the sake of brevity, in this work, we will focus our attention on the IAS/IFRS accounting standards.

The impairment test consists of a periodical verification of the assets’ value, on the basis of the accounting standard IAS 36, according to which physical and intangible assets have to be recorded in the financial statement at a value that cannot be higher than their recoverable value, equal to the higher between the asset’s fair value (less costs to sell) and its value in use. As far as the fair value is concerned, the considerations already introduced as regards the evaluation of the intangible assets acquired in a business combination remain valid.

As regards the value in use, instead, this is defined as the actual value of the future financial flows expected from the usage and the final disinvestment of the asset under evaluation. It is important to underline that the difference between fair value and value in use is not based on the methodology adopted, which can be based, in both the cases, on the actual value of the future financial flows expected, but on the different assumptions that drive the evaluation process: in fact, in the case of fair value, the expectations of market participants are important, whereas in the case of value in use, the expectations of the specific enterprise matter.

IAS 36 gives some important suggestions concerning the determination of future cash flows and of discount rate. As regards the cash flows determination :

- Future cash flows shall include projections of cash inflows and cash outflows from the continuing use of the asset;

- Future cash flows shall consider, if any, net cash flows to be received (or paid) for the disposal of the asset at the end of its useful life;

- Flows shall not include cash flows from financial activities, income tax receipts or payments;

- Flows have to include or exclude the effect of price increases attributable to general inflation (consistently with the discount rate determined, nominal or real rate);

- Cash flow projections have to be based on rational and sustainable hypotheses, on the past results, on the more recent business plan and budgets approved by the management, and they have to cover at the maximum a five-year period (unless particular reasons suggest the choice of longer periods);

- Over the period of analytic projection, it is necessary to use growth rates, g; g rates can be steady or decreasing and they cannot be higher than the growth rates of the products, industries and economies to which the enterprise refers.

As regards the discount rate, the following considerations are suggested :

- The discount rate has to include both the time remuneration and the remuneration of the specific activity’s risk;

- It can not include risks already considered in the cash flow determination;

- It has to be a pre-tax rate (consistently with the flows, pre-tax flows) and, more generally, it has to have the same nature of the financial flows (so, it has to be a pre- or post-inflation rate consistently with the way the flows are determined and, most of all, it has to leave aside the enterprise’s financial structure)

Internally Generated Intangible Assets

The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the IASB and the FASB (27 February 2006), aimed to achieve the convergence between the two standard setters, also included a project aimed to improve the intangible assets’ accounting. In December 2007, a project proposal for the review of the IAS 38, based on a technical paper which became public on 23 January 2007, was submitted to the IASB: at the December meeting, the Board did not deem the inclusion of the project in its active agenda suitable (this also stopped the discussion within the FASB) but, at the same time, recognizing the relevance of the matter, the Board deemed the development of the research and consultation works necessary. To date, it is impossible to predict when the accounting standards IAS and FASB concerning the intangible assets will be reviewed; anyway, it is possible to suggest some reflections on the outstanding issues arising from the project proposal.

The attention is focused on the internally generated intangible assets, and on the limits of their accounting .

- No intangible assets arising from research shall be recognized.

- The recognition of intangible assets arising from development is possible only in certain circumstances (and not provided by the SFAS).

- Internally generated brands, mastheads, publishing titles, customer lists and items similar in substance shall not be recognized as intangible assets.

- There is an inequality of treatment between intangible assets acquired in a business combination and intangible assets internally generated, even if the economic nature of these assets is the same one.

- After initial recognition, an entity is permitted to carry an intangible asset at cost or fair value (less any accumulated amortization and any accumulated impairment losses); in this second case, it is possible to carry periodic revaluations, with reviews of the amortization period and amortization method for intangible assets with a finite useful life.

Anyway, with this last option being tied to the presence of quoted market prices in an active market, it is, in fact, not feasible. The reasons for these choices are attributable to the nature of intangible assets and to the difficulties concerning their identification and evaluation.

Given the premises, it is possible to describe, in a synthetic way, the more signifi cant points, suggested by the technical project proposed early in 2007:

- The identification criteria of intangible assets provided by the IASB’s Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements (Whittington 2008) and, in particular, by the IAS 38 are irrespective of the manner in which an intangible item comes into existence; in other words, the identification criteria can be met both by assets acquired (separately or in a business combination) and by internally generated assets: genealogy is not an essential characteristic of an asset (Upton 2001).

- For operating purposes, it is useful to distinguish two broad types of internally generated assets: those created out of specific planned projects, defined as planned internally generated assets (for example a brand creation) and those that arise from the day-to-day operations, defined as unplanned internally generated assets. The distinction between the two types of internally generated assets is tied, most of all, to the ‘descriptor’ used to identify and define the underlying economic phenomenon (and consequently the unit of account): in the first case, the project represents the natural descriptor; in the second case, in the absence of a specific project, the unit of account has to be defined time after time. For example, the descriptor ‘brand’ can be significant in some cases, but it can be an indefinite concept in other cases.

- To identify the internally generated assets, the technical project suggests a simulation technique: an entity could assume the existence of a business combination in which the entity that has generated the asset internally is acquired. So, the standards provided by IFRS 3 and IAS 38 for the identification of intangible assets acquired in a business combination should be, at least in part, extended to the internally generated intangible assets.

- After having identified the intangible assets, it is necessary to deal with the recognition matter. In this case, the technical paper distinguishes between the cost-based model and the valuation-based model (both provided in the Framework). In the first case, the cost-based model, only planned internally generated assets meet the recognition criteria (probable future economic benefits and reliable measurement of cost), whereas the absence of specific information seems to preclude the possibility of recognizing the unplanned internally generated assets. On the contrary, in the second case, the valuation-based model, all planned and unplanned internally generated assets that satisfy the IFRS 3’s recognition criterion of “reliable measurement of value” should be recognized.

- Consequently, as regards the measurement, if a cost-based model is adopted, all the historical costs incurred for the development of the plan constitute the value of the planned asset, whereas they are not considered for the unplanned assets. On the contrary, if a valuation-based model is adopted, all the internally generated assets, planned and unplanned, “are capable of being reliably measured at fair value to the same degree that IFRS 3 asserts that the fair value of the same types of intangible assets acquired in a business combination are capable of reliable measurement” (IASB 2007).

Identification Of Intangible Assets That Can Be Autonomously Quantified

The problems to be tackled in relation to these assets are the following. why are they not recorded? And which are the criteria to identify and then valuate them?

We have seen that intangible assets directly acquired or inside a business combination are basically recorded. Except for the possibility of capitalizing a few development costs (as allowed by IAS 38), the intangible assets internally generated by the enterprises are not subject to recording even though they fulfill the general requirements for accounting identification.

In valuation practice, three requirements are usually defined for the identification of the intangible assets to be the object of an autonomous valuation, irrespective of the accounting needs :

- The asset must be the object of a significant and quantifiable flow of investments;

- The asset must be at the origin of differential economic benefits, and therefore also in this case specifically identifiable;

- The asset must be transferable, i.e. sellable and assignable to third economies.

Together, the first two requirements indicate that the intangible asset must be at the origin of costs with a deferred utility, while the criterion of transferability on a conceptual level is totally similar to the criterion of separability/transferability used by accounting principles, and can be applied in a more or less rigid way.

The identification process should develop observing a few additional tactics, which concern :

- The analysis of the nature and origin of the assets; and

- The verification of the criterion of dominance.

The Valuation Of Unrecorded Intangible Assets

The identification process alone is able to provide some useful information for the purpose of the subsequent valuation of the subject asset. Let us take for example the degree of innovation of the capabilities from which the asset originates, or the fact that the asset may be protected by IP or contracts .

This and other information should be used in the adopted valuation methodologies. An important aspect, preliminary to the selection of the method, concerns the relation between the intangible asset and the enterprise owning and using it. The asset in fact should be quantified for its characteristics and not for the characteristics of the owner. In other words, if the objective is to attribute a value to the subject asset, then the organizational circumstances of its use should exert no influence.

Obviously, this principle, which is relatively easy to follow for physical assets, may imply many problems for intangible assets which by their own nature oftentimes show a very strong functional relation with the entity generating or using them. It is necessary to :

- Reduce to the bare minimum the influence of entity-specific factors in the

valuation of the subject asset (for example cost of capital factors);

It should also be considered that if the valuation of the intangible assets is used with the purpose of further breaking down the goodwill, the problem of the entity-specific factors appears less significant. In this case, the final purpose is not the valuation of the subject asset but rather the interpretation of the overall goodwill also through the valuation of subject assets.

A further aspect to be considered preliminarily is the placement on the market of the asset. In this respect intangible assets, in relation to one another, may be :

- Identical, as they share all relevant characteristics, such as functionality, duration, methods for use, geographical areas, etc;

- Similar, as they share a few but not all relevant characteristics.

While it is certainly probable to identify a few degrees of similarity between the subject asset and other intangible assets—an indispensable condition, for the valuation process—it is instead very difficult to define two intangible assets as identical. The employable valuation techniques for intangible assets are many and represent an element in the valuation of the enterprise which is receiving increasingly more attention .