Index Funds Offer Advantage of Tax Savings

Post on: 1 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

In recent years, index mutual funds have gained a loyal following among investors who want a convenient, low-cost way to match the market’s performance.

Now, they’re getting favorable reviews for another reason—tax savings.

Because index funds rarely sell securities, they generate little in the way of realized capital gains that must be passed through to shareholders. Until a fund actually cashes in its underlying stock or bond positions, these gains can accumulate on a tax-deferred basis for years.

But first, a qualification: If you hold your mutual funds within an IRA, 401(k) plan, variable annuity or other type of retirement account, you needn’t be concerned about this tax-avoiding angle. Your capital gains will continue to grow tax-free anyway, until you withdraw money.

By contrast, if you have mutual funds in regular, unsheltered accounts, you need to pay taxes on your portion of any capital gains the portfolio manager realizes from trading individual stocks and bonds over the course of the year.

This is where index funds can help.

These portfolios seek only to match the market’s return, not beat it. To do so, they buy the same stocks or bonds included in popular market indexes such as the Standard & Poor’s 500, and in similar proportions.

They don’t make bets on individual companies or industries, and there’s no attempt to time the market.

The result of this passive investment approach is very little portfolio turnover, with minimal realized capital gains that must be passed on to shareholders in the form of a taxable distribution.

Ultimately, that deferred liability need never be paid. When a mutual fund shareholder dies, the taxes that would otherwise be payable are essentially forgiven.

Is indexing an effective way to boost actual, after-tax returns? Yes, according to a recent study by Robert H. Jeffrey of the Jeffrey Co. in Columbus, Ohio, and Robert D. Arnott, president of First Quadrant Corp. in Pasadena.

Writing in the Journal of Portfolio Management, the two investment pros studied the nominal and after-tax returns of 72 large stock funds from 1982 through 1991, including the Vanguard Index Trust 500, which tracks the S&P 500.

On a pretax basis, 15 of these portfolios bested the Vanguard index fund. But after subtracting taxes for capital gains, only 10 of the portfolios did better. And of these, just two—Fidelity Magellan and CGM Capital Development—fared significantly better.

The higher portfolio turnover characteristic of active fund management rarely compensates for the increased capital-gains taxes that must be paid, Jeffrey and Arnott concluded.

The authors specifically cited sector funds and portfolios full of cyclical stocks as among the categories to avoid, as both groups are typically favored by short-term traders and thus exhibit higher turnover.

Index portfolios aren’t the only mutual funds that are loath to sell securities. But as a group, few other fund categories do so little trading.

In fact, a true index fund normally would sell stocks or bonds under only two circumstances:

* When a company gets acquired, goes bankrupt or otherwise falls out of the targeted index.

* When the fund needs to raise some cash to meet shareholder redemptions.

It’s worth emphasizing that index funds are risky to hold during bear markets, as they stay fully invested with no ability to shift into the safety of cash.

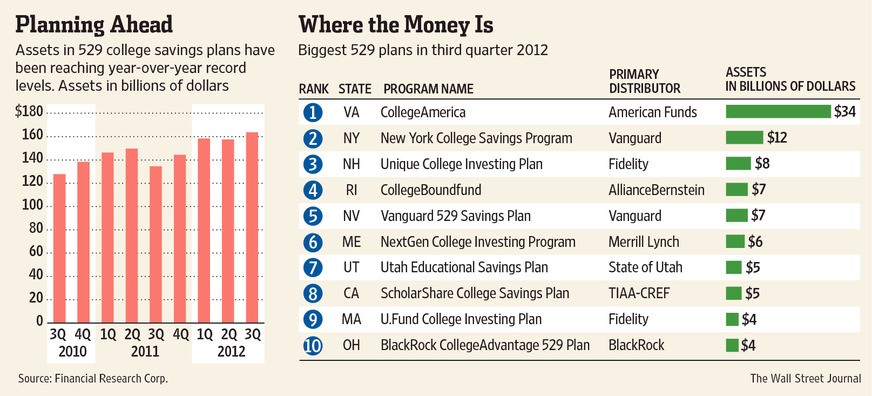

Index mutual funds debuted in 1976 with the Vanguard Index Trust 500. They took a while to get established but have grown more popular recently. Lipper Analytical Services, a research firm based in Summit, N.J. counts more than 110 index funds, up from about 20 a mere five years ago. But not all of these funds are passively managed—the true test.

Many index portfolios attempt to duplicate the performance of the S&P 500, which is dominated by large, established corporations. Others track smaller stocks, foreign stocks, bonds or various investment subgroupings.

Still, indexing appears to work best on big, well-known U.S. and foreign stocks. Why? Because the blue chips are so widely followed by professional analysts that all relevant public information about them is already reflected in their stock prices, proponents say.

Hence, the difficulty of beating the market.

Though this idea remains controversial, it’s clear that smaller stocks and those in emerging foreign markets are less picked over, which makes it easier for shrewd managers to find bargains.

Because true index funds aren’t actively managed, they tend to have low management fees and expense ratios.

The largest such fund, the $7.6-billion Vanguard Index Trust 500, has an expense ratio of just 0.19%—equal to a mere $1.90 annual fee on a $1,000 investment. That compares to 1.22% for the typical growth-and-income fund.

In terms of pretax performance, the Vanguard fund ranked in the top fifth of its growth-and-income peer group over the past five years.