IFRS Coming to America

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are destined to be the lingua franca of the international accounting world.

Approximately 100 countries already require, allow or are in the process of converging their national accounting standards with IFRS. FASB and the IASB have agreed to converge their respective standards. The SEC also has a road map to allow foreign issuers that list on U.S. exchanges to report exclusively in IFRS by 2009.

IFRS is intended to be a more principles-based set of standards rather than the rules-based approach of U.S. GAAP. The two systems (IFRS and U.S. GAAP) differ conceptually on a number of points.

Important differences lie in areas such as the way pre-operating and pre-opening costs are reported and the fact that IFRS prohibits the use of LIFO for inventory valuation. Borrowing costs, fair value, revenue recognition and extraordinary items are also areas of significant differences.

It is important for American CPAs to be familiar with IFRS and the convergence process now so that they can counsel their clients (or companies) on how IFRS could affect their reporting.

Lawrence M. Gill. CPA, J.D. chairs AICPA’s International Issues Committee and is a partner in the Chicago-based law firm Schiff Hardin LLP. His e-mail is lgill@schiffhardin.com .

merican business is fortunate. English has become the language of international commerce. But American CPAs have been less lucky in the international acceptance of U.S. GAAP; International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are destined to be the lingua franca of the international accounting world.

In today’s increasingly international business environment, American CPAs are frequently encountering IFRS as they serve U.S. subsidiaries of foreign companies and foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies and as they assist in cross-border transactions. Fortunately, the standard setters for U.S. GAAP and IFRS are engaged in a convergence process designed to make the two sets of standards compatible.

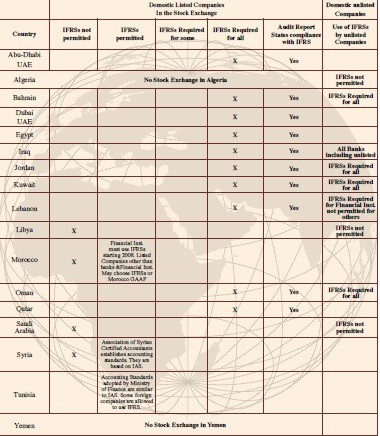

STATE OF CONVERGENCE

Approximately 100 countries require, allow or have a policy of convergence with IFRS. Countries such as Japan, the United States and Canada have active programs designed to achieve convergence with IFRS. China’s Accounting Standards Committee has announced that convergence is a fundamental goal of its standard-setting program, and the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India has taken up the issue of convergence of Indian accounting standards with IFRS. To be sure, not all countries that claim to have adopted IFRS have adopted standards that are entirely consistent with IFRS. Nevertheless, there is undoubtedly a global movement toward convergence.

To some extent, the EU gave global convergence a kick-start when the EU mandated that EU companies with securities listed on an EU exchange prepare their consolidated accounts for all fiscal years beginning on or after Jan. 1, 2005, under IFRS as adopted by the EU. For the most part, the EU has adopted IFRS as promulgated by the IASB, but there have been some exceptions.

In the United States, FASB has engaged in an active effort to seek convergence of U.S. GAAP with IFRS. In 2002, the IASB and FASB jointly pledged, in what has come to be known as the “Norwalk Agreement,” to use their best efforts to “make their existing financial reporting standards fully compatible as soon as is practicable.” On Feb. 27, 2006, the two organizations issued a Memorandum of Understanding (2006 MOU) that not only reaffirmed their objective of developing common accounting standards, but also set forth with some specificity the goals they sought to achieve by 2008.

FASB and the IASB have already made progress under their short-term convergence project, which often resulted in choosing between the U.S. GAAP approach and the IFRS approach. In the 2006 MOU, however, FASB and the IASB both recognized the need to improve standards rather than merely eliminate differences between their two sets of standards. As a result, one of their goals for 2008 is to make significant progress in areas where they jointly believe current accounting practices under both sets of standards need improvement.

The SEC has been highly supportive of convergence. It publicly welcomed the 2006 MOU, noting the SEC’s commitment to a road map for the elimination prior to 2009 of the requirement that foreign private issuers reconcile to U.S. GAAP financial statements prepared using IFRS. All parties recognize that the fewer the differences between U.S. GAAP and IFRS, the easier it will be for the SEC to eliminate its reconciliation requirement.

PRINCIPLES VS. RULES

While IFRS currently fills approximately 2,000 pages of accounting regulations, U.S. GAAP comprises over 2,000 separate pronouncements, many of which are several hundred pages long, issued in various forms and formats by numerous bodies. The difference in volume alone reflects a difference between the historically rules-based approach underlying U.S. GAAP and the principles-based approach underlying IFRS. Consider, for example, the difference between telling your child to be home at a reasonable hour (principles based) and telling her to be home at 11 p.m. and then providing for the 15 contingencies that might justify a different time (rules based).

But it is not simply a philosophical difference between a rules-based approach and a principles-based approach that accounts for the differences between the two systems. The systems differ conceptually on a number of points and can significantly affect an entity’s reported results. CPAs cannot always easily predict the effects of using one system rather than the other. For example, many predicted that the adoption of IFRS by EU financial institutions would introduce significant volatility into their reported results due to IFRS fair value reporting requirements. Results to date have not supported this assertion.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Because of ongoing convergence projects, the extent of the differences is constantly shrinking. FASB’s recent Statement no. 159, The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities, for instance, provides for a fair value option that the statement’s summary calls “similar, but not identical, to the fair value option in IAS 39.”

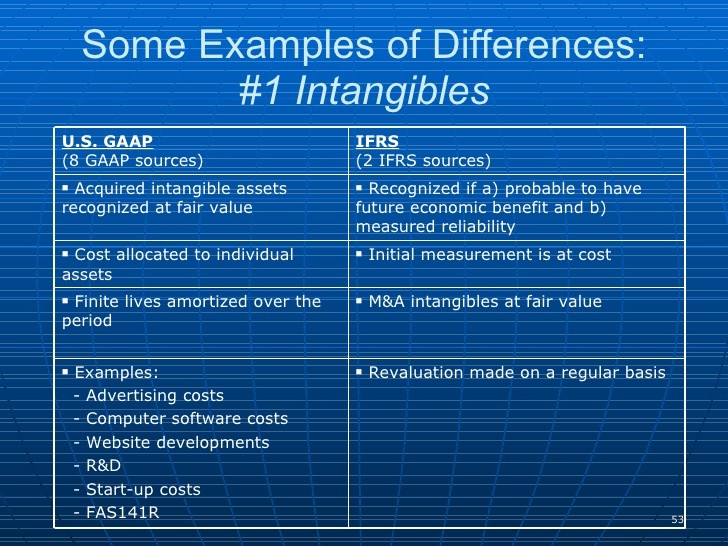

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to identify all of the differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP, the following illustrates some of the differences:

Presentation. Users of IFRS statements quickly become aware of the fact that, while IFRS requires that a balance sheet and an income statement contain certain minimum information, IFRS does not require a precise format for the display of that information.

Pre-Operating and Pre-Opening Costs. The differences between IFRS and U.S. GAAP can result in a difference in the assets appearing on an entity’s books. IFRS requires an entity to expense pre-operating and pre-opening costs and costs incurred in startup, training, advertising, moving and relocation. Any of those assets on a U.S. GAAP balance sheet would disappear in financial statements based on IFRS.

Borrowing Costs. U.S. GAAP, on the other hand, mandates capitalization of borrowing costs for qualifying assets, but IFRS has permitted an entity to elect whether to capitalize or expense borrowing costs for qualified assets, provided the entity is consistent in its approach. Reflective of the convergence movement, IFRS will use the U.S. GAAP approach after Jan. 1, 2009.

Fair Value. Even where the use of U.S. GAAP and IFRS result in the same assets appearing on a balance sheet, the values attributed to those assets may be different. IFRS permits an entity to regularly revalue property, plant and equipment to fair market value. An entity cannot pick and choose under IFRS, however, and if it revalues one item within a class of assets, it must revalue all items within the same class. IFRS provides for crediting increases in values to a revaluation reserve in the equity section of the balance sheet while decreases in values are treated as expenses to the extent the decreases exceed any previous revaluation increases.

For investment property, both GAAP and IFRS approve of a historical cost based method with depreciation and impairment, but IFRS also permits an entity to account for the property on the basis of fair market value, recognizing changes in value as profit or loss.

Obviously, if the two sets of standards result in reflecting different assets and asset valuations, one can also expect they will result in a difference in reported income or retained earnings.

Inventories. IFRS permits an entity to reverse inventory write-downs in certain situations, whereas U.S. GAAP does not. IFRS also requires the recognition of certain development costs that U.S. GAAP accounting does not recognize. In valuing inventory under IFRS, LIFO is prohibited.

Revenue recognition. Reflective of its principles-based approach, IFRS guidance regarding revenue recognition is less extensive than U.S. GAAP. IFRS, for example, does not have specific guidance for software revenue recognition.

Extraordinary items. IFRS prohibits reporting items as extraordinary while U.S. GAAP permits reporting items as extraordinary in the income statement, albeit under very limited circumstances.

SEC , Users Voice Support for IFRS at Roundtable

Never mind convergence—why not just report in IFRS and forget about U.S. GAAP altogether?

It didn’t take long for the question to come up in March at an SEC roundtable on its International Financial Reporting Standards Roadmap, where the very first panel raised the issue—and the panelists seemed to applaud the idea.

Chairman Christopher Cox opened the door in his opening remarks, noting that “virtually everyone—issuers, investors and stakeholders alike—agrees that the world’s cap markets would benefit from the widespread acceptance and use of high-quality global accounting standards.” Replacing the “Babel of competing and often contradictory standards” would improve investor confidence, allow investors to draw better conclusions, and simplify the process and cut costs for issuers, Cox said.

Soon enough, Ken Pott, head of Morgan Stanley’s capital markets execution group, followed that argument to its logical conclusion, noting that “the dramatically increasing acceptability of IFRS may move U.S. companies to decide they’re better off reporting in IFRS if that’s allowable by the SEC.”

Catherine Kinney, president of the NYSE Group, said “a number of large global issuers” already have told the stock exchange that they would “welcome having a choice” of reporting standards and are considering moving to IFRS. If U.S.-based issuers listed abroad continue to report in U.S. GAAP, she noted, European regulators “will have the opportunity—and maybe even the obligation” to question their financials, just as the SEC asks questions of companies that report in IFRS.

“Every change in regulations has unexpected side effects,” she said. “And I think regulators will have to allow U.S. companies to report in IFRS. That will be a further spur to convergence, and a positive development.”

It also would be in keeping with two SEC aims: a more transparent global financial reporting environment and more principles-based accounting standards.

Panelist David B. Kaplan, who leads the international accounting group of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, said he hoped the question of allowing U.S. companies to report in IFRS would not delay the road map’s timetable but otherwise did not object to the idea. Converting U.S. companies to IFRS would mean large-scale educational efforts, knowledge transfer and system changes for the accounting profession, but CPA firms already have begun the process. “At the end of the day, we wouldn’t be asking people here to do any more than what Europe has just done in changing to IFRS,” he said.

KPMG’s partner in charge of professional practice, Samuel Ranzilla, also on the panel, noted that “this complexity discussion is absolutely the right place to put this issue on the table” and that he “supports the elimination of U.S. GAAP reconciliation in accordance with the road map and would ask the SEC to take on front and center the issue of whether international standards are something we ought to be moving toward here in the United States.”

With that discussion on the table, any question about whether IFRS was going to happen seemed moot. Summing up the first panel, Morgan Stanley’s Ken Pott called IFRS “a terrific idea that can’t come fast enough,” and Brooklyn Law School professor and former SEC Commissioner Roberta Karmel said it “can’t come soon enough.” In fact, she advised the commission not to wait until it has solved every little question, but rather to “take the plunge.”

In the end, Citigroup Global Markets’ Managing Director J. Richard Blackett noted that allowing foreign issuers filing in IFRS to come into U.S. markets will “at the margin and perhaps theoretically” raise the cost of capital for U.S. issuers—but “certainly U.S. companies having the option to adopt IFRS will help.”

The SEC announced in April it is planning to publish a concept release about providing U.S. issuers the alternative to use IFRS. Comments would be due this fall.

Cheryl Rosen is a freelance writer. Her e-mail is crosen2@optonline.net .