How Taxes Work For UK Dividend Investors

Post on: 2 Май, 2015 No Comment

A friend of mine mentioned a whle back that the dividends the received from the pawnbroker Albemarle and Bond Hldg (LON:ABM) were now worth more than his entire initial investment. That is a classic example of something that Warren Buffett has called the eighth wonder of the world — the power of compound interest. At a 15% return per year, your annual return will exceed your initial stake in the 16th year and you’ll have ‘tenbagged’ within 17 years. While there are a few stocks that may make an equivalent capital gain, the reality is that so few achieve it and investors often expose them to dreadful risks in seeking out this kind of speculative price move.

However, the flipside of the power of dividend reinvestment is the unfortunate drag caused by income taxes. As Frank Armstrong has observed, taxes are the natural enemy of investors! Unfortunately, the fact that dividends are taxed as income can have a big impact on reported returns from income investing. Historically, dividends have almost always been taxed less favourably than capital gains. According to research by Legg Mason Capital, in the US over the last 50 years dividends have been taxed on average at a rate of 50%. Meanwhile in the UK, dividends are taxed on a sliding scale according to your income band meaning that top-rate tax payers pay an awful lot more for dividend income than capital gains.

But it’s not all bad. You can prevent taxes from eroding your portfolio performance, as long as you remember to always buy them in a tax-efficient wrapper like an ISA or a SIPP in the UK. However, given that the whole tax situation is made so confusing, it’s easy to mis-step. In this article, we’ll try and get to grips with the dividend tax situation and make a few suggestions for maximising total returns.

In essence, dividend investment is basically subject to three forms of tax: stamp duty, capital gains tax and income tax:

1.Stamp Duty

This is a flat tax on buying all shares (but not unit trust shares shares as the trust pays it). If the transaction is paperless, the tax is called Stamp Duty Reserve Tax and you pay a rate of 0.5%. If you use a stock transfer form, then it’s a paper transaction and you pay Stamp Duty on paper transactions at the same 0.5% rate, rounded up to the nearest £5 (but there is no tax to pay if you spend £1,000 or less on the shares). Frankly, this is an arbitrary tax on investing that most sensible commentators think should be repealed but, unfortunately, this looks unlikely to happen any time soon for political reasons.

Of course, stamp duty is not applicable if you’re spreadbetting and, while you might assume that dividends are not payable when spreadbetting, in fact they are. With daily rolling contracts, you should receive a credit to reflect dividends paid on shares and other corporate actions like rights issues, scrips and stock bonuses are also paid too. However, it’s important to calculate the interest charges built into the spread and compare this cost vs. the stamp duty you’re saving out on. While spreadbetting may be attractive over the short-term, it’s likely to be far less attractive for long-term buy and reinvest dividend income investors.

2. Capital gains and capital gains tax (CGT)

A capital gain is made if you sell a dividend stock for more than you paid for it. Each tax year you have a capital gains tax (CGT) allowance which is known as the annual exempt amount. This is the amount of profit you can make from disposing of assets in that tax year without having to pay any CGT. Any profits above this amount are taxed. The profit is added to your taxable income for the year and any part of the profit falling within your basic-rate band is taxed at 18%, anything more at 28%. However, some investments are exempt from CGT such as gilts, most corporate bonds and stocks & shares ISAs. It’s important to keep track of off-setting capital losses but remember — you can’t use losses on ISA investments to reduce Capital Gains Tax on profits from investments outside the ISA.

3. UK Dividend Income Tax

If you have ever been a shareholder in a UK company, it’s likely that at some time you’ve received a dividend cheque in the post and the joy that comes with knowing that this is income that you haven’t actually had to earn. But you also receive with your cheque a tax voucher that shows the amount of the dividend you’ve received from your shareholding and an additional tax credit line. These both add up to your gross dividend income and generally create a bunch of confusion.

Double Trouble: What is this tax-credit anyway?

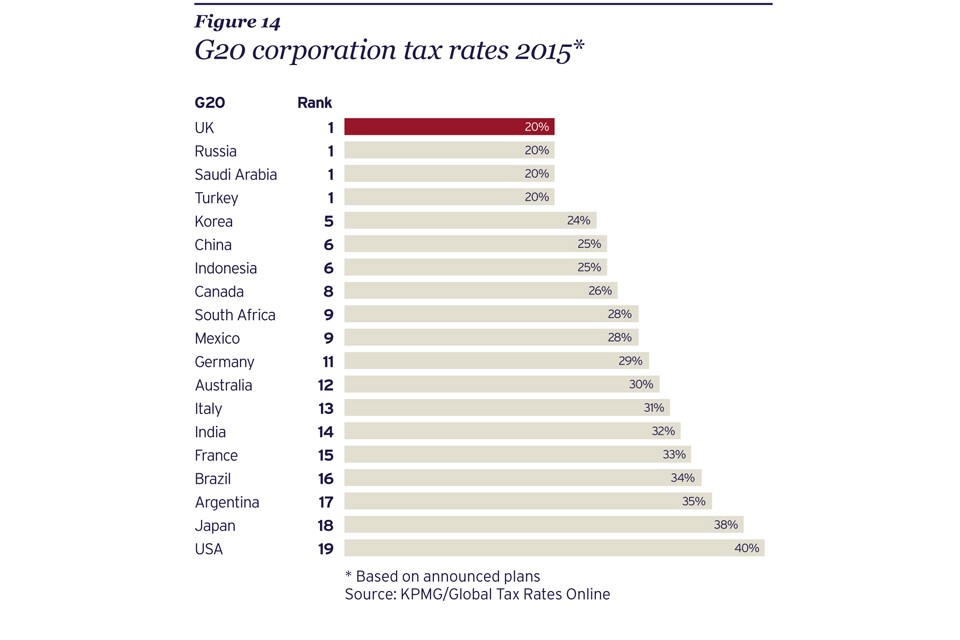

Dividends are paid out of a company’s net (after tax) profits. But dividends are treated as income by the taxman, and as a result are liable to be taxed at the prevailing rate of income tax. This effectively leads to a form of ‘double taxation’ whereby if a company paid out all its profit as dividends, the cash received by the investor would be taxed twice — first by corporation tax, secondly as income tax. This double taxation though is a real headwind for investors to sail against, so some countries provide a limited tax-credit on dividends.

Since 6th April 1999, all UK company dividends have carried a tax credit of 10%. The tax credit applies to all dividends regardless of whether the shares are held directly or in a fund such as a unit trust, OEIC or investment trust. The 10% tax credit can be set against your tax liability, but your ability to use that tax credit depends on whether you are a nontaxpayer, a basic rate taxpayer or a higher rate taxpayer. This effectively means that basic rate taxpayers get their dividends taxfree, while still hitting the higher tax payers at an effective rate of 25% or 36.1% depending on the tax band.

How It Works

At the basic level this works a bit like PAYE. The dividend issuing company is deemed to be paying the basic rate of income tax (10%) for you at source on your gross dividend income, before sending you your post tax dividend cheque. Once this whole shenanigan has been applied, the dividend you actually get in the cheque is the actual dividend advertised by the company. Phew.

First up, it’s worth being clear on the difference between the tax rates on dividend income and other forms of income: