Hold on to That Mutual Fund

Post on: 4 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

This article originally appeared in The Washington Times on November 2, 2003.

Mutual funds are suffering the glare of regulators’ high beams because some sharpies trade the funds too quickly (“market timing”) or after regular business hours (“late trading”). Even The Washington Posts most astute financial writer, James Glassman, was swept up in the excitement. He wrote: “The mutual fund scandals are spreading. New revelations show that more and more managers betrayed the mass of their customers by illegally favoring a few fast-buck artists.”

Actually, what may have been done “illegally” remains unclear. New York allows “deception, misrepresentation, concealment, suppression, false pretense, false promise” and perhaps an evil grin to be prosecuted as fraud, regardless of intent. But most of Mr. Glassmans readers probably take “illegally” to mean a provable criminal offense under federal law.

Late trading at the previous days price violates a 1968 Securities and Exchange Commission regulation. But a regulatory edict is not a law, and the SEC deals only with civil sanctions, not crime. Market timing is not even a civil offense, although one case involves fund managers, which might qualify as insider trading.

As for the mutual fund companies themselves, most allegations of impropriety concern the fact that their sales literature implies fund managers “may” — at their discretion — attempt to thwart frequent traders. Failure to thwart frequent trades may therefore lose customers, which could hurt the stock price of affected mutual funds companies.

From a mutual fund investors point of view, however, neither the funds redemptions nor its legal bills have any impact on the value of the mutual funds themselves. The value of a mutual fund depends only on the value of stocks in the fund. So why dump a mutual fund because of “scandals” unless you have a better investment alternative?

Mr. Glassman noted that Morningstar, which rates the mutual funds, has nonetheless recommended that investors shun all funds accused of something or other. That has to be Morningstars worst recommendation of all time. Mr. Glassman himself advised: “If you own good funds that are under scrutiny by the authorities, hold on to them for now, until more facts come to light. But if the funds are marginal performers, dump them. Even if the shenanigans prove isolated, however, this is a good time to consider alternatives to conventional mutual funds. The best choices fall under the broad rubric ‘exchange-traded funds,’ or ETFs.”

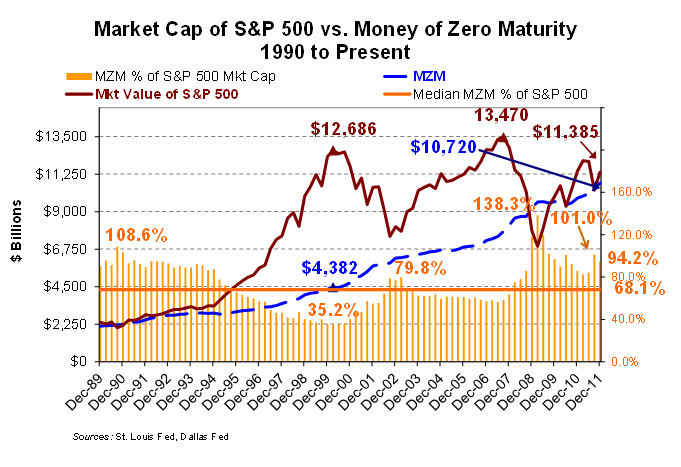

The biggest of such funds — SPDR or “spiders” — matches the S&P 500 stock index. So, what would have happened to your wealth over the past five years if you had taken the advice to dump mutual funds and replaced them with spiders?

Look at Lippers list of the 125 largest, most popular stock funds. Putting aside two that are too new, the other 123 yielded an average total return of more than 30 percent over the past five years. The five-year return of the Spider trust, by contrast, was only 4 percent. Only 19 of the big funds performed as badly as or worse than Spiders, and some of those 19 were index funds. Only two of the several mutual fund companies currently under regulatory scrutiny have many funds among the largest (namely, Janus and Putnam), but those, too, have to be judged on results, not sentiment. If market timing and late trading is really such a big deal, then funds that tolerate it will do poorly and lose business. But the evidence that this is a big deal is really very weak.

Until very recently, no sensible financial adviser would have dreamed of advising people to dump mutual funds simply because speculators like to speculate. The only reason such arcane issues suddenly rose to best-seller status in the crisis-of-the-month club is because an adventurous young academic entrepreneur put a number on it: “By some estimates,” wrote a Wall Street Journal editorial, “market timing costs long-term investors $5 billion a year, and late trading costs them another $400 million.”

The source of those mysterious estimates is two unpublished papers by a young assistant professor at Stanford, Eric Zitzewitz. Just two years out of grad school, he has already discovered a simple and foolproof way to become infinitely wealthy by timing the markets: “For example, if the U.S. market has risen since the close of overseas equity markets, investors can expect that overseas markets will open higher the following morning.” Investors may expect all sorts of things, but betting that all the worlds markets move together is hardly a sure thing. However, links of just that sort between assorted markets form the basis for estimating gains from market timing that, by definition, are said to be losses for those who dont take such risks.

Mr. Zitzewitz wrote that “evidence from a sample of funds suggests long-term shareholders are losing about $5 billion per year across all asset classes.” More than $4.3 billion of that suggested $4.9 billion was from international funds. There is no such loss at all big cap U.S. stocks, and the suggested loss for smaller stocks amounts to twelve-one-hundredths of 1 percent.

Other alleged costs from market timing are said to include the need to hold more cash that might have been better invested. But if timed trades are equally balanced between sales and redemptions, there would be no net drain on cash. As for the $400 million supposedly lost to late traders, that number is obviously too small to take seriously in relation to stock mutual funds the Investment Company Institute valued at $3.6 trillion this August.

Unless your mutual funds are international, market timing is not a topic worth more of your time than it takes to read this. Even for international funds, Mr. Zitzewitz notes in passing that his own estimated cost to long-term investors happens to be 100 times larger than the estimate from the published study of a different team of economists.

The notion that mutual fund investors are routinely losing huge sums to prescient day traders is a dubious theory backed by questionable estimates. If there really are such losses, they pale in comparison to the losses investors will suffer in the future if the result of all this poking and probing is that many people become scared away from the largest, most successful mutual funds.

The fact is that our nations most popular mutual funds have performed remarkably well over the past five years despite unusually challenging times. Whenever forced to choose between economists’ estimates and stock market facts, stick with the facts.