Fundamentals of Fixed Income Investing Price

Post on: 25 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

What are fixed income securities?

Fixed income investments, commonly known as bonds and money market securities, come in a variety of forms. They are simply loans made by an investor to a corporate or government borrower. The borrower, also known as the issuer, typically promises to pay a fixed amount of interest—known as the coupon—on a regular basis until a predetermined maturity date. At maturity, the issuer promises to return the principal amount of each bond—often referred to as the face or par value—to the investors holding them.

What are some types of fixed income securities?

The fixed income market is diverse, spanning a broad range of securities. Some of the more common types include:

- U.S. Treasuries: issued by the federal government, the only entity permitted to print money, and thus considered the safest type of bond.

- Money market instruments: issued by corporations or government entities and considered relatively low risk because maturities are usually very short.

- Investment-grade corporate bonds: issued by corporations deemed by the major credit rating agencies to be in good financial condition and likely to meet payment obligations.

- High yield (junk) bonds: issued by corporations considered to be at higher risk of default (i.e. missing interest or principal payments) due to financial difficulties.

- Mortgage- and asset-backed securities: issued by a government agency or financial institution; the coupon payments represent cash flows from a pool of loans, such as mortgages, auto loans, and credit cards.

- International bonds: issued by governments or corporations outside of the U.S.

- Tax-free municipal bonds: issued by state or local governments; interest payments are exempt from federal and, in some cases, state taxes. Some income may be subject to the federal alternative minimum tax.

The annual interest amount is found by multiplying the coupon rate by the security’s face value, usually $1,000. For example, a bond with a 5% coupon and 10 years to maturity will pay $50 of interest each year for 10 years. Payments are usually made semiannually but may occur at other intervals.

How is the coupon rate determined?

Coupon rates are a function of the prevailing interest rate and market demand for a particular type of security at the time of issue. They also vary depending on the time to maturity and the issuer’s credit quality. Generally, longer maturities result in higher coupons. Also, coupons are inversely related to the issuer’s creditworthiness—the higher the credit quality, the lower the interest rate required by investors.

What is the relationship between coupon, yield, and total return?

Investors can buy or sell bonds in secondary markets between the issuance and maturity dates. Although a bond’s coupon and face value are fixed, its price and yield will fluctuate with changes in interest rates and other factors. As a rule, prices and yields move in opposite directions.

For example, consider if you bought a $1,000 bond that pays a $50 annual coupon, and interest rates have risen since your purchase, resulting in higher coupons for similar-quality bonds. As a result, your bond would sell for less than face value in the secondary market since buyers could obtain a higher coupon from other bonds. If your bond’s price has fallen to $950, for instance, its yield would adjust upward from 5.0% to 5.2% (i.e. $50 coupon divided by $950). The situation would be reversed if interest rates fell after your bond was purchased.

Total return is a better representation of the value of a fixed income investment than yield or coupon alone. Total return includes the value of coupon payments as well as appreciation or deprecation in a bond’s price. For instance, a bond that paid a 5% coupon and increased in price by 2% for a particular year would provide an investor with a total annual return of 7%.

What are some of the risks of fixed income securities?

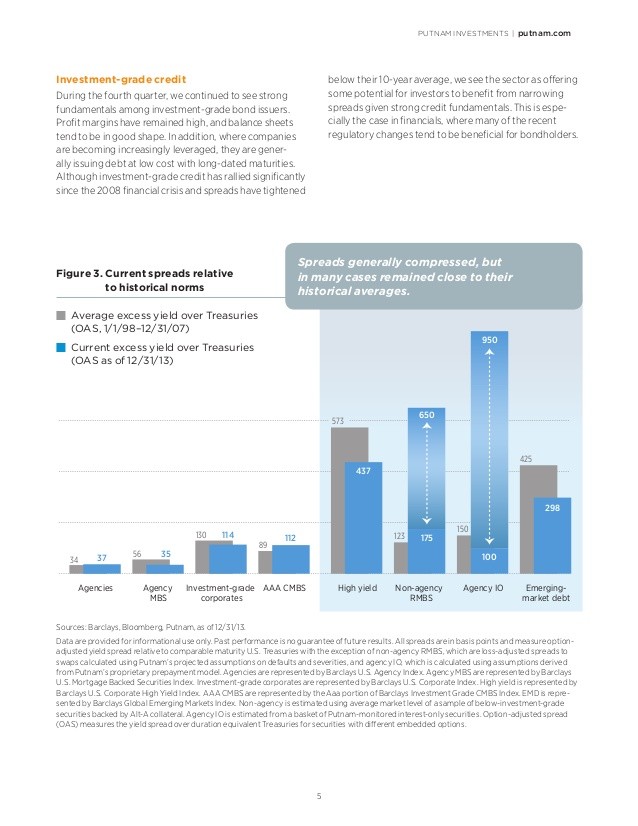

As shown above, interest rate changes cause bond prices to rise or fall. Generally, prices of longer-maturity bonds respond more sharply to changes in interest rates than those with shorter maturities. Although a loss is not realized unless you sell your bond prior to maturity, there is an opportunity cost if comparable bonds are paying higher coupons.

Another consideration is credit risk, which is based on the likelihood that an issuer will default on its obligations. Lower-quality bonds offer higher yields than higher-quality bonds as compensation for the extra risk involved, but their prices can be more volatile. A rising yield may indicate deteriorating financial conditions for the issuer and will result in price depreciation and potential loss.

In addition to these risks, an investor in international bonds faces the risk of exchange rate fluctuations. For instance, if the euro falls in value relative to the U.S. dollar, returns will be reduced for a U.S. investor who owns bonds denominated in euros. The opposite would occur if the euro increased in value versus the dollar.

What are some of the ways for an investor to gauge these risks?

A quick way to approximate the impact of interest rate risk on price fluctuations is to look at a security’s duration, a statistic expressed in years. Multiplying the duration by a possible change in interest rates approximates how much the security’s price would change. For example, a bond with a four-year duration would decline about 4% if interest rates rise by one percentage point, and vice versa.

Bond ratings from one of the major credit rating agencies provide insight into credit risk. Using Standard & Poor’s rating system, higher-quality, investment-grade bonds are rated BBB or above, while high yield bonds are rated BB or below. Ratings are revised as an issuer’s financial prospects change, which will result in fluctuations in price and yield.

Fixed income securities generate income, and some have the potential for capital appreciation. Although diversification cannot assure a profit or protect against loss in a declining market, an allocation to bonds can reduce the overall volatility of a portfolio. In a well-allocated portfolio, the allocation of bonds, equities, and short-term investments will change over time depending on an individual’s goals and time horizon. Within the fixed income component of a well-diversified portfolio, 70% might be invested in investment-grade bonds, 20% in high yield bonds, and 10% in international bonds. Tax-free municipal bonds may also be advantageous for investors in higher tax brackets.