Financial Statement Analysis

Post on: 8 Август, 2015 No Comment

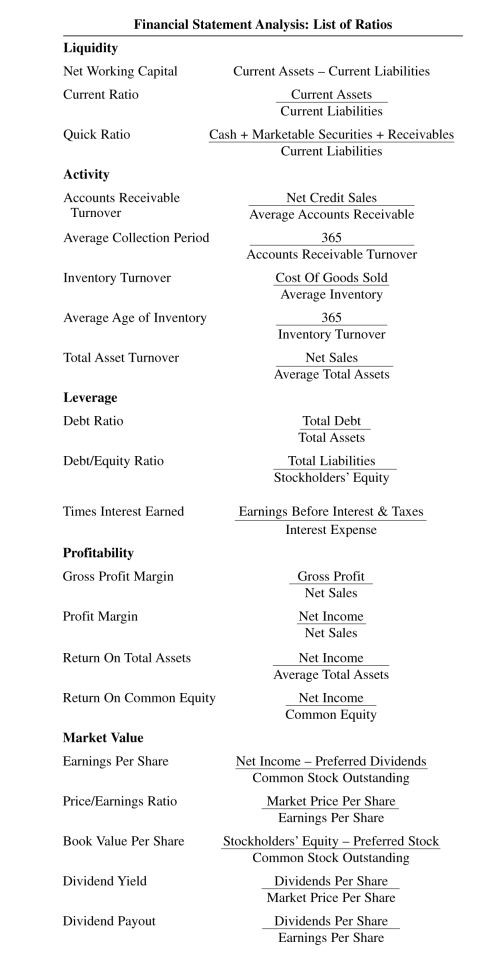

Another method to analyze financial statement information involves the use of ratios. Ratios are useful in showing the relationships among financial statement data and also can be useful in comparing one company with another or analyzing the same company over time.

Ratios often are classified into different categories. Within each category, the ratios measure a common element, such the company’s profitability or ability to pay its current debts. Sometimes the terminology of these different categories varies, but even with differing terms, the concepts are the same.

Liquidity Ratios

Debts cannot be paid with assets such as accounts receivable and buildings but must be paid with cash. Liquidity ratios help measure a company’s ability to pay its current debts as they become due. If a company can pay its debts when they are due, the company is said to be solvent, and so liquidity ratios sometimes are referred to as solvency ratios.

Current Ratio

Current ratio helps assess the company’s ability to pay its debts in the near future. Current assets are assets that will be converted into cash, sold, or used typically within a year and include assets such as cash, short-term investments, accounts receivable, interest receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses. Current liabilities are the debts that will be paid or settled within a year by providing goods or services and include items such as accounts payable, the portion of any long-term debt that is due typically within a year, interest payable, wages payable, taxes payable, accrued liabilities, and unearned revenues.

Quick Ratio

The quick ratio (sometimes referred to as the acid test ratio) is a more conservative liquidity measure. The numerator contains the assets that can be turned into cash most quickly. Inventory is removed from the current assets because is slower to convert to cash.

A common rule of thumb is the acid-test ratio should have a value of at least 1.0 to conclude a company is unlikely to face liquidity problems in the near future.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios measure a company’s success (or failure) in earning a profit. Profitability ratios compute the relationship between profit and some other financial statement item, such as assets, sales, equity, or shares of common stock outstanding.

Common profitability ratios include the following:

- Gross margin on sales

- Profit margin on sales (return on sales)

- Return on assets

- Return on equity

- Dividend payout ratio

Gross profit margin

Gross margin (also called gross profit) is the excess of sales revenue over the cost of goods sold. Thus, gross margin represents the amount of sales revenue left, after covering the cost of the product sold, to pay all remaining business expenses and have some profit left over.

Profit margin on sales

Profit margin on sales takes the bottom line (net income or net profit) after all expenses are subtracted from revenues and compares it with net sales revenue. Again, this can vary widely from industry to industry. This ratio sometimes is called return on sales.

Return on assets

The return on assets (ROA) ratio measures how effectively management is using its assets to generate a profit.

Return on equity

The return on equity (ROE) ratio measures how well management is maximizing the return on the stockholders’ (owners’) investment in the business. For this reason, the ratio sometimes is referred to as return on investment.

Payout ratio

The dividend payout ratio is often of interest to investors because it indicates how much of a company’s wealth is distributed to the common stockholders. Preferred stockholders typically have a fi xed, stated amount that will be received as dividends each year, and so this ratio is calculated for the common stockholders as follows:

Asset Management Ratios

Asset management ratios (also called turnover, effi ciency, and sometimes activity ratios) indicate the company’s effectiveness at using its various assets. The asset management ratios we will discuss here are the following:

- Days sales outstanding

- Accounts receivable turnover

- Inventory turnover

- Asset turnover

Days sales outstanding

This ratio calculates the number of days it takes the company to collect its accounts receivables on average. The lower this number is, the better, because a company cannot pay its bills with receivables, only with cash.

Accounts receivable turnover

The accounts receivable turnover ratio is closely related to the days sales outstanding. Instead of computing the average number of days that accounts receivable are outstanding, this ratio calculates the number of times accounts receivable are collected during the year.

Inventory turnover

This ratio indicates how quickly on average inventory is sold (i.e. turns over). How long does inventory sit on shelves before it is sold?

Asset turnover

Average total assets is computed as follows:

Average Total Assets = (Beginning Total Assets + Ending Total Assets)/ 2

The beginning total assets will be the total assets shown on the prior year’s balance sheet, since last year’s ending balance equals this year’s beginning balance. Since all assets are included in the computation, this is a more general indication of how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate sales. Specifically, it indicates how many dollars of sales are produced for every dollar invested in assets.

Leverage Ratios

Leverage ratios (sometimes called coverage or capital structure ratios) measure a company’s long-term ability to pay its debts as they become due. Leveraging means using other people’s money to generate profit for a company. The leverage ratios we will introduce are

- Debt ratio

- Times interest earned

Debt ratio

The debt ratio measures the amount of debt in relation to the total assets of the company. Recall from our discussion in Chapter 1 that the assets came from somewhere: either from outsiders (what you owe) or from owners (what you own).

Times interest earned

Interest must be paid on debt and it must be paid on time or the company risks having its creditors call in the loan. To get an indication of a company’s ability to pay the annual interest it owes, times interest earned can be calculated.

Sometimes it can be difficult to interpret in a meaningful way all the dollar amounts presented in a set of financial statements. For example, if one company has liabilities of $10,000 and another company has liabilities of $10,000,000, is the fi rst company less risky? Maybe, maybe not. It depends in part on the size of the company (how much in assets does each company have?) and the company’s industry (what is normal?).

A useful way to analyze financial statements is to perform either a horizontal analysis or a vertical analysis of the statements. These types of analysis help a financial statement reader compare companies of different sizes, which can be difficult to do when the dollar amounts vary significantly, and evaluate the performance of a company over time.

The horizontal and vertical analysis approaches are similar in that the dollar amounts reported are converted to percentages. The approaches differ in the base used to compute the percentages.

Horizontal analysis

Horizontal analysis focuses on trends and changes in financial statement items over time. Along with the dollar amounts presented in the financial statements, horizontal analysis can help a financial statement user to see relative changes over time and identify positive or perhaps troubling trends. We will use the income statement information for Dell to explain how one might prepare a three year horizontal analysis.

In one horizontal analysis approach, a base year is selected and the dollar amount of each financial statement item in subsequent years is converted to a percentage of the base year dollar amount. Assuming 2011 is the base year, 2012 and 2013 revenues were 101% and 93% of the base year amount, as shown in the following calculations:

62,071/61,494 = 101%

56,940/61,494 = 93%

Similar computations would be made for Dell’s remaining income statement items as shown below.

In addition to base year comparisons, dollar and percentage changes from one year to the next could also be analyzed. For example, 2012 revenues increased by $577 or 0.9% over the previous year, and 2013 revenues decreased by $5,131 or 8.3% over the previous year, as shown in the following calculations:

(62,071-61,494)/61,494 = 0.9%

(56,940-62,071)/62,071 = -8.3%

How is the base year selected? That’s up to the individual performing the analysis. Fraud examiners who are investigating a case of fraudulent financial reporting, for example, probably will select the last year in which they believe no fraud occurred as the base year in order to estimate the extent of the fraud. In other situations, the choice will depend to some degree on the purpose for which the reader is using the financial statements. Are you trying to decide whether to buy (or sell) stock now that a company has experienced a signifi cant change such as new management or the introduction of a new product line? Then perhaps the base year will be the last year before the change. Essentially, the choice of the base year is up to the individual financial statement user.

Are these proportional increases that we calculated for Dell good? Perhaps the competitors in the same industry are increasing even more. To interpret the proportional changes, the reader will need additional information, such as the industry averages and/or the changes for a particular company that the financial statement reader also is considering for investment purposes.

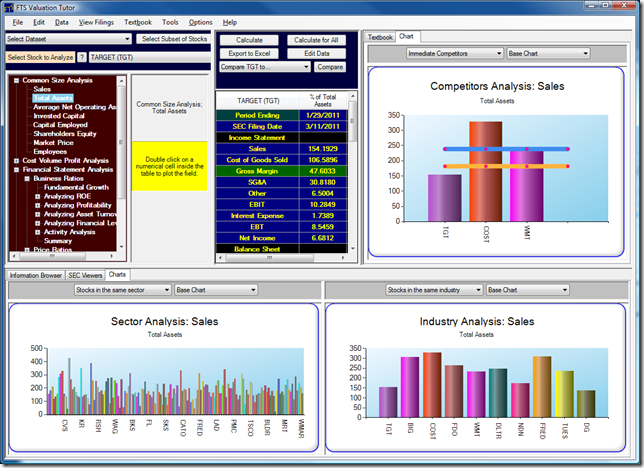

Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis sometimes is referred to as common-size analysis because all of the amounts for a given year are converted into percentages of a key financial statement component. For example, on the income statement, total revenue is 100% and each item is calculated as a percentage of total revenue. On the balance sheet, total assets are 100% and each asset category is calculated as a percentage of total assets. In the balance sheet equation, total assets are equal to total liabilities plus equity; thus, each liability and/or equity account is also calculated to be a percentage of this total (i.e. total liabilities and equity are 100%). Vertical or common-size analysis allows one to see the composition of each of the financial statements and determine if signifi cant changes have occurred. We will use the balance sheet information for Dell in to explain how one might prepare a three year vertical analysis.

After each year’s total asset amount is set as 100 percent (or total liabilities plus stockholders’ equity, since the amounts must balance), the various accounts’ dollar amounts are converted to a percentage of the total assets. When the calculation is complete, the sum of the percentages for the individual asset accounts must equal 100 percent. The sum of the percentages for the various liability and equity accounts also will equal 100 percent.

Vertical analysis of a balance sheet will answer questions relating to asset, liability, and equity accounts, such as the following:

- What percentage of total assets is classifi ed as current assets? Current liabilities comprise what percentage of total liabilities and stockholders’ equity?

- Inventory makes up what percentage of total assets? Is this changing significantly over time? If so, is it increasing or decreasing? (These answers could lead to additional questions such as the following: If it is increasing, could this indicate that the company is having trouble selling its inventory? If so, is this because of increased competition in the industry or perhaps obsolescence of this company’s inventory?)

- Accounts receivable makes up what percentage of total assets? Is this changing significantly over time? If so, is it increasing or decreasing? (These answers might lead to additional questions such as the following: If it is increasing, could this indicate that the company is having trouble collecting its receivables? If it is decreasing, could this indicate that the company has tightened its credit policy? If so, is it possible that the company is losing sales that it might have made with a less strict credit policy?)

- What is the composition of the capital structure? In other words, total liabilities make up what percentage of total assets and total stockholders’ equity makes up what percentage of total assets?

Vertical analysis of an income statement helps answer questions such as the following:

- What percentage of revenues is cost of goods sold?

- What is the gross profit percentage?

- What is the mix of expenses (in terms of percentages) that the company has incurred in this period?

Since total revenues usually are set at 100 percent, vertical analysis of the income statement essentially shows how many cents of each sales dollar are absorbed by the various expenses.

In the case of Dell, the organization appears to be fairly stable over the three years of data we have. Again, these percentages won’t provide you with a lot of insight in and of themselves. The analysis is more meaningful when the percentages are compared with competitors’ or industry averages or for a long period of time for one company. However, if some unreasonable fluctuations are noted for one company over time and/or the percentages are signifi cantly different from industry averages, the possibility of fraudulent financial reporting should be considered.