Finance And Trading Terms Explained What Is A Carry Trade

Post on: 19 Август, 2015 No Comment

Stay Connected

Even professional traders and investors can’t always speak the language of colleagues working in a different segment of the financial world. With that in mind, we’ve introduced this weekly column, looking at one esoteric or potentially misunderstood finance or trading term every week. After we defined the wonderful word contango in last week’s inaugural edition, we’ll now tackle carry trade.

What Exactly Is a Carry Trade?

In a carry trade, an investor borrows money at a low interest rate in order to invest in an asset that’s likely to provide a higher return. This strategy is most often used in the foreign exchange market, where investors borrow money in a low-interest-rate currency and invest in assets with a higher interest rate in another country.

Jill Scalisi, a former senior vice president of both JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM ) and the now-defunct Lehman Brothers (she was there in 2008), as well as the current CEO of her own company, Scalisi Skincare. helped us simplify the definition. As she puts it, A carry trade is any time you borrow one thing to invest in another and you can make money with a positive spread.

Currency Carry Trade 101

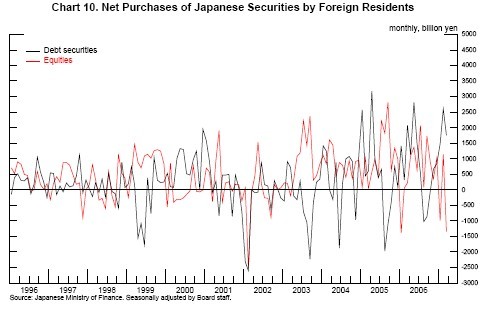

To explain the currency carry trade, Scalisi drew our attention to the yen carry trade, which began in the mid ’90s, peaked in 2008 before the financial crisis, and made a comeback last year. It’s known to be a driver of strength in the US stock market today. If you look at the USD-to-yen exchange rate and the S&P 500 Index (INDEXCBOE:SPX ) chart, you’ll see how closely this relationship tracks. In this carry trade, investors are able to borrow yen at a very low interest rate and use it to invest in higher-yielding US-denominated assets, such as the US stock market.

Let’s say it’s the beginning of a new year and you want to take advantage of the yen/USD carry trade. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say the exchange rate is 100 yen to $1 (which is close to the actual current rate of 103.92 yen to $1). You borrow 10,000,000 Japanese yen from the Development Bank of Japan and then convert those funds into $100,000. With your American cash, you buy the SPX. Let’s say that in that given year, the SPX returned approximately 30% (as it did in 2013) and the Japanese interest rate was 0%. So, in this carry trade, you made 30% for the year. In this scenario, the carry trade would work as long as the US economy feels strong; the exchange rate between the US and Japan doesn’t change. Here lies the rub: Exchange rates can be very volatile.

So what happened in 2008? The market began to deteriorate, volatility increased, and investors began to worry. As such, they sold their riskier, high-yielding American assets (equities, subprime real estate, etc.) and invested in safer, lower-yielding assets (US Treasuries). Scalisi explains that this phenomenon, called a flight to quality, brings about the unwinding of the carry trade. As she tells us of 2008, The unwind of the carry trade exacerbated what was already happening in the market. The market was going down and there were even more sellers. Depending on the size of a particular carry trade in the market, the unwind can have dramatic effects.

Interest-Rate Carry Trade

Generally, banks make money by borrowing at cheap interest rates and lending at more expensive rates. So, say Bank A borrows at 0.15% (the national average rate at which banks pay depositors like you and me on our saving accounts). Then it offers loans at 4%, making the potential carry profit 3.85%. By doing so, Bank A finances long-term assets (its loans) with short-term liabilities (money from depositors that can be withdrawn at any time). This works in the bank’s favor as long as short-term interest rates remain lower than long-term rates.

However, when it comes to a crisis like we saw in 2008, investors viewed the market as getting riskier and demanded a higher interest rate for their short-term assets. Bank A now has to pay more to finance its loans, so the interest-rate carry trade falls apart.

This is the fate that befell many major corporations as well as banks. They ran into financial trouble because they borrowed cheap, short-term money to fund their long-term positions. When that short-term money dried up, they had nothing with which to fund those long-term positions.

Since 2008, investors have been much more careful when it comes to carry trades. As Ed Grebeck, CEO of Tempus Advisors, explained to us about a carry trade, The difference between higher long-term and lower short-term interest and foreign exchange rates alone is not enough to compensate for the risk of using it, unless investors also include the likelihood of the carry trade unwinding in their pricing and required return on capital.

Despite that, Grebeck believes that the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing is an example of a large-scale carry trade. By quadrupling the US monetary base from $800 billion to $3.6 trillion, the Fed has driven short-term interest rates close to zero in hopes of stimulating the economy. As Grebeck said, I fear the consequences when this carry trade unwinds.