Evaluating Credit and Counterparty Risk

Post on: 22 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

by Kathleen Hughes, Head of Global Liquidity for EMEA, J.P. Morgan Asset Management

Credit and counterparty risk has fallen since the height of the global financial crisis, but it remains one of the most important concerns for corporate treasurers. Indeed, treasurers need look no further than the ongoing fiscal issues in the Eurozone (particularly the threat of sovereign default in Greece) to see why credit and counterparty risk always needs to be evaluated carefully and systematically.

I n this article we take a closer look at credit and counterparty risk, explaining what it is, how it can be assessed and measured, and how it can be evaluated and managed within a cash portfolio.

What is credit and counterparty risk?

Credit and counterparty risk arises when an investor enters into a transaction with some form of payment obligation from another party, be it with a bank, a company or a government institution. This is because there is a risk that the bank, company or government will not be able to meet its repayment obligations.

Credit and counterparty risk simply refers to the risk that an issuer will default. The greater the potential for default, the higher the level of credit and counterparty risk.

For example, if an investor buys a debt security from a corporate issuer that gets into financial difficulties, there is a risk that the issuer may fail to repay the principle on the loan, or meet its interest payments. If this happens, then the issuer is said to be in default. Credit and counterparty risk simply refers to the risk that an issuer will default. The greater the potential for default, the higher the level of credit and counterparty risk.

However, the day-to-day concern for treasurers is not simply that a company or government will default, but whether there is a perceived risk that it might. A downgrade, or just the possibility of a downgrade to the credit quality of a debt security, can have a negative impact on price and liquidity, and lead to losses or a breach of investment policy guidelines.

The negative impact that credit downgrades can have for investors has been highlighted recently in Greece, where liquidity in the Greek government bond market dried up and short-term yields surged after Standard & Poors cut Greeces sovereign credit rating to sub-investment grade status. The situation in Greece has also shown how counterparty risk can spread, as the threat of contagion has led to sovereign downgrades in other highly indebted Eurozone countries (Portugal and Spain).

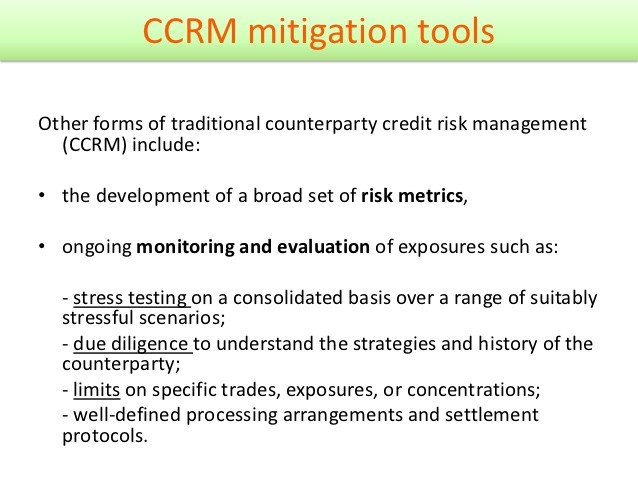

Risk must be measured comprehensively

Its therefore imperative that treasurers ensure that the credit quality of all the securities that they invest in is always fully assessed and that counterparty risk is managed very carefully within a cash investment strategy. Treasurers must also ensure that they know their full exposure to any particular counterparty.

For example, a company may have counterparty exposure to a particular bank through investments such as deposits, short-term securities and bonds. It may also use the same bank for lending, transactional services and managing foreign exchange and interest rate risks.

Furthermore, if the company invests in money market funds it may also have indirect counterparty exposure to the same bank, as the bank may issue commercial paper or may provide liquidity for the asset-backed commercial paper that the money market funds invest in. Therefore the total counterparty exposure to the bank may be much greater than expected.

If you wish to read the rest of this article, please login to your myTMI account

or simply register now for free.

You will then also be able to read online, download and print the article.