Equity investing Too much risk not enough reward

Post on: 22 Август, 2015 No Comment

PEOPLE saving for their pensions and other long-term commitments tend to assume they should put a lot of their money in the stockmarket. Over the long run, goes the theory, equities will always produce higher returns than safer assets such as government bonds and cash because they are riskier (more volatile, in other words) and because shareholders benefit from economic growth whereas bondholders do not. That excess return is known as the “equity risk premium”.

Experience during the second half of the 20th century seemed to bear out the theory. The premium was sizeable, and investors therefore poured a large proportion of their assets into equities.

In this section

Yet in retrospect it looks as though the circumstances of the times, rather than the immutable laws of finance, may have been responsible for the size of the premium. Government-bond returns were savaged by inflation in the 1960s and 1970s, while equities benefited from the absence of the wars and depression that had marked the first half of the century.

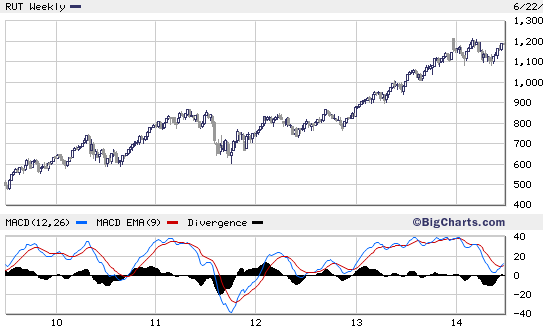

In recent years the premium seems to have evaporated. The Tokyo stockmarket is 75% below the peak it reached at the end of 1989. Treasury bonds easily outperformed American equities over the ten years to the end of 2011. The addiction to equities may itself have been part of the reason for the premiums decline. Just as the belief that American house prices could never fall fuelled the subprime lending boom, so the cult of equity pushed share prices to stratospheric levels. With values so high, future returns were bound to be low.

Time to pay up

Surely, after ten fairly dismal years for stockmarkets, returns from equities should be healthier in future? Not necessarily. The key measures determining future returns are the current dividend yield and prospective dividend growth. The dividend yield is now far below its historic average and dividend growth has struggled to keep pace with GDP. Equities may offer better future returns than government bonds (which were selling off this week), but a reasonable estimate of the premium is only four percentage points a year (see article ).

That is a problem for savers. Many pension funds were counting on equities to keep rising, and—notwithstanding dodgy accounting which, in the public sector, is hiding some of the holes—are now in deficit as a result. The problem is widespread, but sharpest in American local-government pension funds, most of which assume that their investment portfolios will earn 8% a year and fund their schemes accordingly. They invest in a mixture of equities, Treasury bonds (which currently yield 2%) and corporate bonds (which yield 3-4%). If the risk premium is four percentage points, then equities will earn 6%, and pension funds will fall well short of their target. Those pension funds will either have to increase contributions sharply, which means raising taxes or cutting services, or reduce benefits, which may mean prolonged battles with the trade unions and in some cases may require changes in state constitutions.

Companies also face a bind. Many have moved away from expensive pension promises linked to salaries and adopted schemes where the employee takes the investment risk. Even so, S&P 500 companies still have a $450 billion, or 25%, shortfall in their pension funds. In Britain the figure is £92 billion ($144 billion), or around a sixth, for FTSE 350 companies.

Policymakers are under pressure from businesses to lengthen the period over which they must eliminate the deficit. But if they get more leeway, they risk an even bigger shortfall in later years. And if, on the other hand, companies are forced to pay up now, they could be diverting cash away from projects that might create jobs and boost the recovery.

Individuals who are funding their own pensions, or who are members of less generous defined-contribution schemes from their employers, also need to take note. They should save more. If they want a comfortable retirement their contributions need to be more than 20% of current salary, rather than the current average of just 10% or so.

The high returns from equities in the late 20th century made investors lazy. Such returns may not come back. If employees want a decent retirement income (or if employers are to keep their promises), they must put more money aside.