Economics Malaysia Mythbusting Government Debt Edition

Post on: 29 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Mythbusting: Government Debt Edition

Teh Chi-Chang of Refsa was on BFM radio the other day promoting his new book:

I sometimes feel like Im banging my head against a wall.

Put me down as one who isnt worried at all about Malaysias debt level or deficits as they stand. Plenty of financial market analysts and laymen appear to be concerned, but I dont know many economists who think we have an immediate or even medium term problem.

Disclaimer: I have not read the book, and for the sake of my sanity, I dont intend to. If you want my full thoughts on the subject of fiscal policy and government debt, please check the FAQ .

Before jumping into a critique of the issues brought up in the show, I have to admit I was cringing while listening through it; theres enough confusion over the term national debt and this show just adds to it.

While by common consensus worldwide the term national debt is usually taken to mean central government debt, in Malaysia it is expressly used in officialdom to refer to the external debt of the country (both public and private) and not government debt. The confusion arises when people talk one thing, and the government presents data on something else. Ever since I found out that little nugget, Ive avoided using the term.

In any case, my thoughts on some of the issues:

- Debt to GDP rising to 100% by 2020 the host brought up the old prediction of Prof Mohd Ariff that debt to GDP, based on the then growth rates, would reach 100% by 2020, and Chi-Chang agreed it was possible.

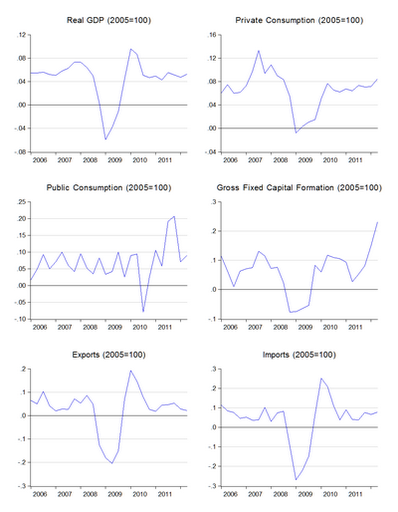

If you calculated the compound annual growth rate of the debt to GDP ratio from say 2006-2010, you would get a growth rate of around 6% per annum. Extrapolating based on that, youd breach 100% of GDP by the 2020-2021 time frame. So theyre right, right? Problem is, almost all the increase in the debt to GDP ratio occurred in just one year 2009. It was relatively stable before and has been stable since:

For Malaysia to get to the 100% debt to GDP ratio by 2020, we would need in essence to undergo four more recessions of the length and depth of the Great Recession over the next 8 years. That sounds a lot less plausible.

For one thing, as far as the development budget is concerned, the amounts are pretty much set in stone. The development budget is actually set for a five year term corresponding with each 5-year Malaysia Plan, and this is the only portion of the annual budget which is intentionally funded by borrowing.

With respect to operating expenditure, much of it is sticky non-discretionary spending salaries, pensions, debt service charges, grants and transfers (including to state governments) form about two thirds. Ah-hah but that leaves another third to cut up right? But one half of this is subsidies, and only the other half is supplies and services where the most egregious examples of government waste can be found and what makes the AGs report so entertaining to read.

Personally Id start with subsidies first, but saving 10% of the total budget off procurement alone is pretty ambitious — you’d have to cut off two-thirds.

With respect to the limit that Chi-Chang mentions, it does in fact exist but theres two of them. One is an administrative rule governing total government debt, but this is subject to change on the authority of the minister alone. The other is a hard legal limit, butit is not in reference to total government debt, only to locally issued government securities.

Let me repeat that the 55% legal limit does not apply to total government debt, it only applies to locally issued government securities. Loans dont count, external debt doesnt count, the National Savings Bond doesnt count. The outstanding value of locally issued government securities (both conventional and Islamic) amounted to RM387.7 billion at the end of 2011, equivalent to about 44% of GDP (source: Bond Info Hub ). Thats a long, long way from 55%.

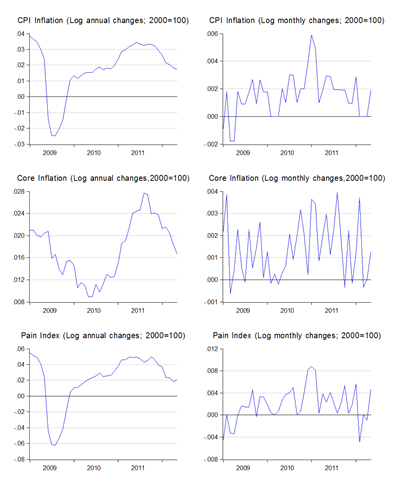

First, any increase in the money supply from debt monetisation would only have inflationary consequences if the economy is already at full employment. That’s not a given by any means.

Second, the inflationary impact of government borrowing is predicated on the government actually spending the monies borrowed (subject to the full employment condition above). In the scenario under discussion during the program repayment of maturing debt through monetisation that doesnt happen, as the money goes to bondholders. Most holders of government debt (e.g. banks, insurance companies, pension funds) aren’t looking for cash to fund consumption, they’re looking for risk-free, interest or profit bearing investments.

Third, we can’t ignore the reaction of a central bank operating with an interest rate target (as BNM does). Since monetisation of maturing debt or even direct central bank purchases of government securities at issuance (which is the precise technical definition of printing money) results in an increase in the money supply, that would reduce the market interest rate. In the presence of an interest rate target, the central bank would then need to issue its own debt to reduce the money supply, to reorient the market interest rate towards its target rate. In effect, government debt is replaced by central bank debt and we get status quo ante.

So no, printing money doesn’t automatically equate to higher inflation.

Given that EPF safeguards the retirement savings of its members, its primary consideration is and must be capital preservation, not return maximisation and that means government securities. In any domestic financial investment environment, there is in fact nothing that is safer both from a credit perspective and from a liquidity perspective. Only MGS is regularly traded on the money markets; equities are subject to occasional capital loss, and higher price volatility.

It might actually be more pertinent to ask why EPF, given its mission, is not investing even more of its portfolio into government securities as opposed to riskier property development or equities, especially since the EPF Act also requires EPF to invest 70% of its portfolio in government securities (a legal requirement it has been unable to meet for years).

If you still dont think its safe to invest in government securities, then you will be glad to know that for every Ringgit in members contributions, EPF has RM1.56 in invested assets to back it up.

To conclude, there is and remains a lot of confusion regarding the wisdom of continuing to maintain deficits and debt financing, especially in an uncertain economic environment. Personally I dont think Malaysias position is at all very vulnerable, though Im obviously in a minority here.

It doesnt help when there continues to remain plenty of myths and misapprehensions regarding government debt, inflation and the economy. Even without this post, Ive written reams on the subject already; I suspect Ill have to continue to write more.