Debt to Equity Ratio Analysis

Post on: 12 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

This column was adapted from the December 2006 issue of Motley Fool Inside Value.

For companies as for people, debt is a key part of any financial picture. When you’re analyzing a prospective investment, it’s important to get a handle on the effect that debt may have on the company’s prospects. Debt ratios measure financial solvency and can give a glimpse into capital structure. It’s easy to find out how much debt is reported on the balance sheet, but this alone won’t tell you much.

Debt is not always a bad thing — using leverage (financing a project with debt rather than equity) will normally increase shareholder returns, because the cost of debt (interest — tax) is lower than the cost of equity. But overusing leverage leaves the company at risk during a recession or a downturn, particularly in a cyclical industry. Debt ratios are a good starting point to keep track of a company’s ability to withstand such periods.

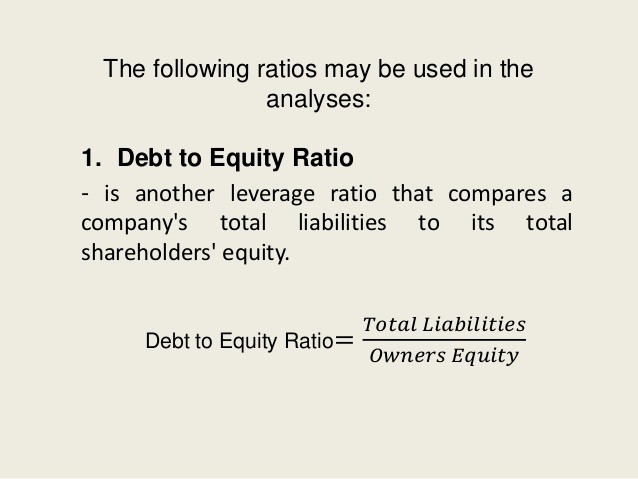

The debt-to-equity ratio is the most commonly used metric and appears on most financial websites. The simple formula for the calculation is:

Debt to Equity = Total Debt / Shareholder’s Equity

Debt should also include any interest-bearing liability on the balance sheet, such as capital leases, as well as off-balance-sheet debt, which can be found in the footnotes to the financial statements. The two most common off-balance-sheet items are operating leases and future obligations to employees and retirees, such as unfunded pensions and health benefits. It is no small surprise that the Federal Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is proposing that these items all be included on the balance sheet.

Building in capital and operating leases

Retailers are a good example of companies that generally have off-balance-sheet debt in the form of operating leases. There’s nothing suspicious here — these leases are being reported properly according to GAAP. However, operating leases represent a firm obligation to pay lease costs over a number of years, just like debt. Capital leases are shown on the balance sheet but are not usually included in D/E ratios found on financial websites. These future obligations can be discounted to find an equivalent debt value. (Dr. Aswath Damodaran’s site provides a handy spreadsheet — oplease.xls.)

Let’s check out the numbers for home improvement giant Lowe’s ( NYSE: LOW ). Its D/E ratio of 28% would look good for any company (a D/E of less than 30% is generally considered good). However, if we add in the debt equivalent of capital and operating leases, the picture changes.

At 52.7%, the adjusted D/E ratio is considerably higher than the 30% rule of thumb, but is no cause for alarm for Lowe’s. Of course, a company still must maintain interest coverage and cash flow for debt repayments. Interest coverage — EBIT (or operating income) divided by interest payments — measures a company’s ability to cover its interest expenses and reflects on capital adequacy, solvency, and credit rating. Lowe’s produces ample cash to cover payments, and is in no danger of becoming insolvent any time soon.

D/E wrinkles

The D/E ratio has wrinkles similar to other equity-based ratios, including the possibility that a company can have a negative or distorted equity base. Consider Western Union ( NYSE: WU ). which has been loaded up with debt by former parent First Data ( NYSE: FDC ) to the point that it has negative equity. As a result, we can’t calculate a D/E ratio. This was a deliberate capital decision by First Data and isn’t unusual in spinoff situations. Western Union throws off so much cash from operations that it has sufficient funds to pay interest, pay down debt, buy back shares, and fund capital spending — but the D/E ratio can’t guide us here.

Some companies buy back so many shares that the stated shareholder’s equity can be misleading. The originally issued shares show up on the balance sheet at par value (usually between $0.01 and $1 per share). However, when they’re repurchased, they are put into the treasury — and subtracted from shareholders’ equity — at the purchase price. Consider Anheuser-Busch ( NYSE: BUD ). It has debt of $8.2 billion and shareholders’ equity of just $3.8 billion, for a staggering D/E ratio of 217%.

A casual observer might take one look at this number and pass up the opportunity to invest. But the company’s share buyback history shows a massive $15.3 billion in treasury shares and gives us the clue that the D/E ratio is distorted. Without those buybacks, the D/E drops to a more reasonable 43%.

So keep an eye on a company’s debt — but keep in mind what’s really driving those numbers.

Philip owns shares of First Data and Western Union. First Data, Western Union, and Anheuser-Busch are Inside Value recommendations. The Fool has a disclosure policy .