Collateralized Debt Obligations Buyer Beware

Post on: 24 Июль, 2015 No Comment

GARP Risk Review (Global Association of Risk Professionals) September/October 2005 Issue 26, published with permission. Tavakoli Structured Finance retains the copyright.

Investors transacting in CDOs must hurdle a variety of different obstacles in order to succeed. Janet Tavakoli examines the main hazards investors should consider when trading these credit instruments and explains how banks can potentially mislead investors and regulators when they sell tranches of synthetic CDOs.

Today’s collateralized debt obligations (CDO) market is very muddled. Large investment banks are taking advantage of less sophisticated investors by dumping poorly performing loans in their laps, and even the more educated investors face a variety of hazards when they transact in CDOs. Investment banks contend that the challenges posed by the present CDO market are simply an overhang of imperfect deals done a few years ago. However, the truth is that both old deals and new deals are contributing to the current lack of transparency.

Making matters even more confusing, the character of the transparency void differs somewhat depending on whether we are looking at the cash or the synthetic (derivativebased) CDO market. Today’s investments and today’s secondary market are chiefly yesterday’s CDO issuance. Cash deals, in particular, have very long average lives — often up to 15 years, with even longer legal final maturities. The consequences of these deals will stay with us a long time.

Unfortunately, every day, new deals are being brought to market that are not only ripe with moral hazards but also have virtually zero transparency. What are the key hazards and what steps can investors and bank arrangers take to protect themselves in the risky CDO market? Let’s take a closer look.

Mark-to-Market Hazard

When assessing the CDO market, one key moral hazard to consider is that many cash assets — such as distressed loans— are difficult to mark-to-market, and the investor must rely on the manager for pricing of the underlying assets. If a deal is a market-value deal and the manager earns fees based on the fund performance, there will be a temptation to mark up the prices of the underlying portfolio of assets. And there is currently no mechanism for the investors to verify the pricing.

The 2002 Beacon Hill scandal demonstrated how a “market-value deal” could go wrong. The Securities and Exchange Commission alleged that the managers of Beacon Hill, a hedge fund, marked up the prices of its mortgage-backed securities shortly after increasing their performance fees. While the prices of assets in Beacon Hill’s portfolio were rising, market prices were dropping.

Even more recently, I received a phone call from a managing director of a large hedge fund that is trying to market a private placement for a CDO in partnership with a top-tier investment bank. The bank and the hedge fund have been marketing a market value CDO for which the underlying assets are even less transparent — and for which market pricing is even less available — than the assets in the Beacon Hill fun

The proposed final maturity of this CDO is 10 years. Its underlying assets are high-yield mezzanine investments, distressed debt, bank loans and equities. The equity tranche, sold as common shares, is half of the proposed $1 billion deal (or $500 million).

This is the hedge fund’s first foray into managed CDOs, and its targeted investors are high-networth individuals and financial institutions who can buy in minimum increments of $10 million. Expenses are 20 basis points on the total collateral — or $2 million per year. Management fees are 1.0% ($10 million per year) and the manager will earn an additional 20% on any return above 8%. However, since investors have no way of verifying if the prices are accurate or whether they are being paid “returns” with their own initial investment money, this CDO structure is ripe for abuse.

It is also important to remember that SEC regulations do not allow the advertisement of private placements. What’s more, it is not customary to make cold calls on these products, since they should only be sold to investors capable of analyzing the risks. Yet, I received a cold call from one of the hedge fund’s managing directors.

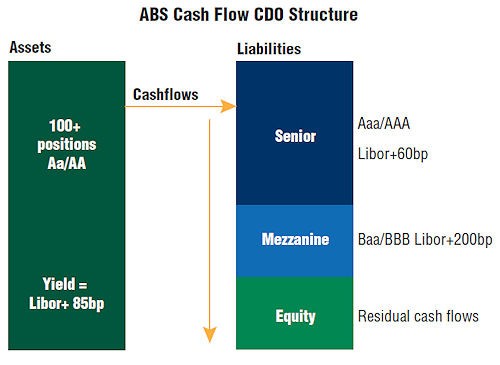

Cash Flow Hazard

In CDO transactions, another potential moral hazard involves the claim to deal cash flows. If a deal manager has a claim on the equity cash flows, for example, there is a conflict of interest between the manager and more senior noteholders. Investors should be particularly wary of deals in which four structural conditions are met; these conditions are dangerous because they can tempt managers to behave against the interest of the noteholders.

The first condition is that losses are allocated in reverse order of seniority, and loss deductions are limited to the initial investment of each tranche investor; the second condition is that excess spread does not accrue to the benefit of any of the noteholders and is not available to absorb losses; the third condition is that the manager does not have adequate restraints on his or her ability to cause a deterioration in the quality of the underlying portfolio; and the fourth condition is that the manager has a claim on the excess spread.

Once the equity is claimed by a deal manager, the next most senior noteholder bears additional losses. When losses exceed the initial equity investment, all of the residual cash flows are diverted, to the benefit of the manager. The manager then has an incentive to trade out of good credits into credits on negative credit watch — or even into lower rated but higher-spread credits if there are no constraints prohibiting this.

This recently happened in a cash CDO deal in which even the integrity of the single A tranche of the CDO was compromised. The portfolio was originally investment grade; however, due to aggressive trading to create excess spread, the portfolio ended up with a junk rating. The single A investor threatened litigation, and the manager reached a settlement agreement with the investor.

Market Size, Moral Hazard and Single-Tranche Synthetic CDOs

Credit derivatives trading adds a new spin to risk for investors, because it is much easier to manipulate the tranching of a single-tranche CDO to the disadvantage of the investor. Investors are not, however, alone in underestimating the risk of these deals.

Investment bank arrangers, for example, often do not know how to quantify the value of single-tranche CDO trading books — partly because they wish to report the size of the synthetic CDO market by counting only the sold tranches. But the truth is that the risk of the arrangers’ position is equivalent to the remaining tranches of the full notional amount of the synthetic CDO.

For instance, if the arranger sells a $250 million mezzanine tranche of a $5 billion CDO, the risk position has the impact of the remaining $4.75 billion synthetic CDO, in terms of Value at Risk (VaR). In the recent past, when deal arrangers sold each tranche of the synthetic CDO and then sold protection in the credit derivatives market on each portfolio position, they were fully hedged. But since single tranche trading books usually sell only the mezzanine (the middle) tranche and then “delta” hedge, they are riskier than fully hedged positions.

Theoretically, one should make more money than the fully hedged position when using a delta-hedging strategy, because one has more risk. That hasn’t been the market experience very often, however. In fact, single-tranche books often make even less money for greater risk, because traders make additional credit bets or make a bet on hedge ratios. When traders lose money on the bets relative to a fully hedged position, the trading book is making insufficient income relative to the risk— and that should show up in lower bonuses

But while this fact should unveil itself, it often does not, because senior management has no idea what is happening in the trading book relative to customary CDO business. Cash CDO deal arrangers, not surprisingly, are irritated by this disconnect with reality.

Measuring Risk

In simplified terms, risk is measured as VaR in single tranche CDO deals. The sold tranches of synthetic CDOs are notional slices of a much larger CDO, and the equivalent risk of the unsold CDO tranches remains on the arranger’s books. However, the sold tranche only bears a horizontal slice of the risk of the entire CDO.

The typical hedge for the sold tranche is to sell credit default swaps (CDS) that are a vertical slice of the risk of the notional amount sold. But the hedge ratio is a best guess.

At the outset of the hedged position for each bespoke transaction, it appears as if the arranger is making more income than if it had fully hedged the entire CDO notional amount (in the trillions of dollars for 2005) — but the VaR is greater. The income from this partially hedged position has often proved over time to be lower than the arranger would have enjoyed if it had fully hedged its position by selling all of the tranches of the synthetic CDO.

Currently, investment banks arranging these deals want to report only the notional amount of the tranches they actually sell; however, this is very misleading. The basis for the risk is the full notional amount of these deals. When investment banks talk to investors, they talk in terms of the full notional amount. But when talking to regulators, investment banks are tempted to report only the notional amount of the sold tranche.

The main reason this still occurs is because bank arrangers have, in the past, executed unprofitable deals when credit spreads were very tight. Unfortunately, however, this isn’t immediately obvious when one sells a single tranche and then hedges it with insufficient income.

Credit spreads have often been very tight in the past couple of years. The return on the implied equity has typically been under 10%; it has only been higher when credit spreads have been very wide. For single-tranche hedges, this means that the income on the CDS used to hedge the position is too low for the risk. Moreover, if one considers the full notional amount of the CDO, it is easy to see that arrangers took on too much risk for too little reward.

Model Mania

Trading desks that previously couldn’t make money managing single-name CDS trades are now declaring victory in “delta” hedging. Originally, in Europe, trading desks shorted mezzanine and went long the credit risk (i.e. sold CDS protection) on all of the names in the portfolio. Senior managers balked as the trading desk positions ballooned. But trading desks eventually came up with the idea of shorting the mezzanine tranches and “delta” hedging the risk.

Delta hedging provides trading desks with a way of obscuring that they are long credit risk, because they can claim to be hedged. But if I had to grade hedging the long equity credit risk by shorting the mezzanine tranche, it would only get a C-. Every hedge, including a bad hedge, looks good when it is initially put on in a static environment. For example, when GM and Ford were downgraded in May, investment banks claimed this was a correlation snafu. But it was merely an exposé of bad hedges.

Looking at the recent past, the smart money in the CDO market was ahead. Savvy investors took on investment grade, first-loss risk at wide levels and hedged as far back as November 2004 by purchasing credit-default protection on these credits as a hedge.

The Shape of Things to Come

Investors are discovering that the synthetic CDO market presents unique challenges relative to asset-backed securitizations. The flexibility offered by synthetic instruments leaves certain structures with more moral hazards and a greater lack of transparency.

Since many of the CDOs include the same names — especially when indexes are used as portfolio reference entities— investors in more than one CDO face concentration risks; similarly, investment banks and hedge funds now face more challenges when they attempt to hedge their positions.

Investment-grade, synthetic securitizations from 2000 and 2001 were plagued with names that defaulted, like Enron, Worldcom, Kmart and Adelphia. Moreover, recent securitizations will probably fair no better since they include companies that are begging for trouble — names such as Toys-R-Us, Delphi and GM. As an investment class, the this sector appears more vulnerable to downgrades and to mark-to-market risk.

In the future, investors will be less likely to make automatic investments in indexed products or stock portfolios. However, there should be increased demand for fundamental credit analysis of individual names, clarity of ratings and structural protection for synthetic CDOs. (See table below.)

CDOs: Potential Hazards for Investors

There are many different issues that investors must consider before entering into any CDO transaction. Here are a few of the most important:

- Arrangers sometimes “optimize” portfolio selection to have the riskiest portfolio allowable given the credit constraints, in an effort to maximize the spread.

- Arrangers sometimes play games with the tranching, eroding investors’ protection with less subordination than the deal warrants. Arrangers could, for example, include names like Ford Motor Credit and GMAC in the finance risk bucket, while simultaneously filling up the automotive risk bucket. This type of maneuver concentrates credit risk and artificially increases the diversity score.

- Arrangers sometimes arbitrage the credit default swap contract documentation so that they get the most favorable language and the CDO investor gets the least favorable language.

- Arrangers may provide inadequate cash flow structural protections for the CDO investor.

- Investors are often unaware that the ratings across rating agencies are not comparable for CDOs. They fail to negotiate for more income when their particular rating is disadvantageous, relative to that of another rating agency.

- Naïve investors often fail to participate in all available cash flows, such as collateral coupon spreads.

- For synthetic, single-tranche CDOs (also known as bespoke tranches, STCDOs or custom CDOs), the investor and the arranger often have a conflict of interest. The portfolio choice — including credit and correlation— favors the arranger.

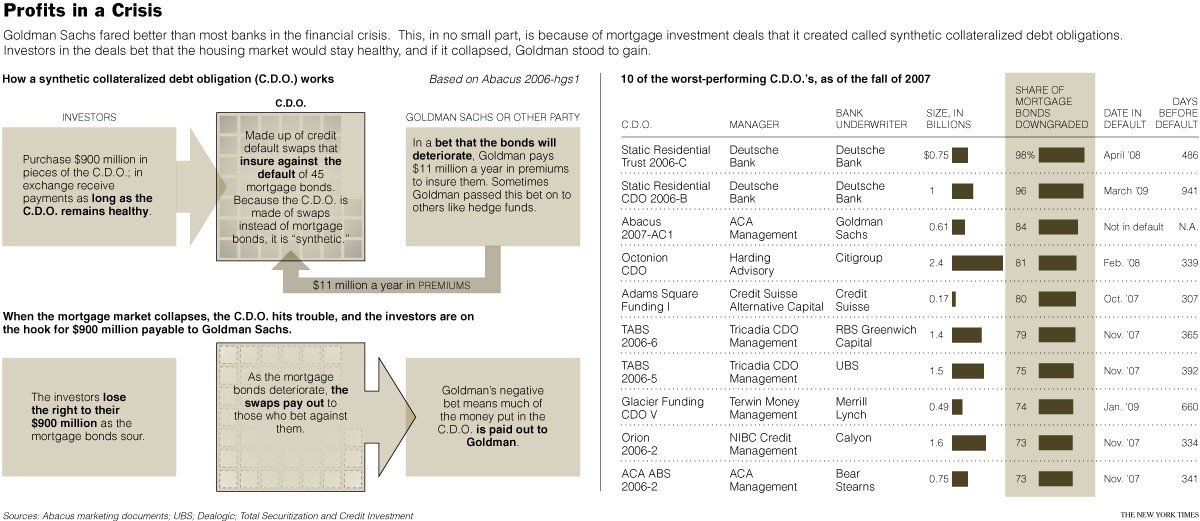

Endnote: This article was published in 2005. The “Magnetar” structures and the ABACUS 2007-AC1 structure, among many others, illustrate the abuse in synthetic CDOs and STCDOs that grew even more prevalent during the subprime synthetic CDO securitization era through the end of 2007. There widespread manipulation, fraud, and abuse in the credit derivatives and collateralized debt obligations markets. Many of these abuses are detailed in my 2003 book, Collateralized Debt Obligations and Structured Finance. The specific issues that contributed to the global financial meltdown are detailed in the second edition, Structured Finance & Collateralized Debt Obligations (Wiley, 2008).

Tavakoli Structured Finance, Inc. retains the copyright for this article. It was reprinted with TSFs permission in GARP Risk Review (Global Association of Risk Professionals) September/October 2005 Issue 26 under the title: “CDOs: Caveat Emptor.” Clients may have a formatted pdf upon request.

See also: The Elusive Income of Synthetic CDOs , Journal of Structured Finance. Winter 2006 Volume 11, Number 4

For more in depth analysis, read Structured Finance & Collateralized Debt Obligations. 2nd Edition, by Janet Tavakoli, Wiley 2003, 2008.